RECOIL OFFGRID Survival Interview With Tom Sarge, Trauma Therapist

In This Article

Survival, at its core, is not just about enduring the physical challenges of a harsh environment — it’s about conquering the mind. When crisis strikes, it’s often the ability to remain calm and focused that separates those who adapt from those who fall apart. While many obsess over the right tools or skills, the true test lies in mastering our mental and emotional state. In moments of extreme pressure, clarity of thought can become the most powerful weapon we possess.

Few understand this balance between mental toughness and survival better than Tom Sarge. He believes that true resilience starts from within, long before you encounter danger. His philosophy centers around mental preparedness, a concept that often takes a back seat in the world of survival training but proves crucial when facing the unexpected.

In our recent conversation, Sarge shared how his years of experience have shaped his unique approach, blending psychological strength with practical survival techniques. What follows is an exploration of how he has made mastering calm his core strategy for overcoming adversity.

Can you tell me about your background and what led you to where you are now?

Tom Sarge: Sure. I’ve been in the mental health field for 25 years. I started back in the late ’90s, training under Dr. Salvador Mnuchin, one of the most famous family therapists. He wrote about a dozen books before passing away, but I had the chance to train with him after graduate school. Preparedness has been a part of my life for as long as I can remember.

Growing up, we didn’t call it prepping. My grandmother lived through the Depression, and my parents grew up poor, so they knew how to grow food and be self-sufficient. My dad was in the 82nd Airborne and went to survival school in Alaska. He passed those skills on to me, but again, it wasn’t labeled as survivalism back then — it was just common sense.

I didn’t even hear the term “prepper” until Doomsday Preppers came out. To me, it was just how we lived.

Did your background influence your decision to become a trauma therapist?

I’ve moved around in the mental health field, working with different populations — kids, teenagers, seniors. Trauma work is inevitable in this field because most people have experienced some form of trauma. We categorize them as “little T” and “big T” traumas. Little T’s might be something like a bad car accident, while big T’s are life-threatening events like sexual assault or combat trauma. How people process trauma depends on their background and prior experiences.

About a few years ago, I got trained in EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing), a treatment modality that’s quite effective. I started working exclusively with first responders, many of whom are also veterans, and their families.

How do previous experiences shape how people react to trauma?

Early experiences, especially in childhood or adolescence, can influence how we react to trauma later in life. It’s not an exact science — having childhood trauma doesn’t guarantee PTSD later — but it’s something we consider.

Core beliefs are a big factor. Between ages 4 and 9, you’re learning the “rules” of how the world works. For example, in my family, it was a core belief that you don’t hit women. That was drilled into me, and it became a core value. Later, when I trained in martial arts with a female instructor, I had a hard time applying enough force in coed classes because of that core belief. That’s an example of how early beliefs can affect us later in life.

Trauma can come from anything that challenges your core beliefs. If you’ve always seen your home as a safe place, and then it’s destroyed in a hurricane or someone breaks in, that can cause trauma. It’s about how that event shakes the foundation of your belief system.

What mental traps do people fall into during high-stress survival situations?

Planning ahead is crucial, but you can’t predict every scenario. Take the example of hurricanes in Asheville — people there aren’t used to that kind of disaster. In places like Charleston, where I live, we expect hurricanes every year, so it’s our responsibility to plan for things like gas shortages, power outages, or flooding.

Even with preparation, everyone experiences the fight-flight-freeze response. First responders and soldiers are trained to override the freeze and flight response, but most people aren’t. It’s important to recognize when that response kicks in and use techniques like sensory grounding to stay focused.

Can you explain more about what fight-flight-freeze feels like and how it impacts people during emergencies?

When the fight-flight-freeze response kicks in, your body releases adrenaline and cortisol. Your heart rate goes up, your breathing gets shallow, and your muscles tense. This is your body preparing to fight, run, or freeze. It’s a survival mechanism that has kept humans alive for thousands of years, but it’s not always helpful in every situation.

For someone who’s not trained to handle it, this response can feel overwhelming. Your thoughts might race, or you could feel paralyzed and unable to make decisions. The key is recognizing that it’s happening and finding ways to calm your nervous system so you can think clearly again.

What are some practical steps people can take to manage this response?

One thing people can do is practice diaphragmatic breathing. Breathe in slowly through your nose for 4 seconds, hold for 4 seconds, then exhale through your mouth for 4 seconds. This technique helps calm the nervous system and brings down that fight-flight energy.

Another helpful tool is sensory grounding.

By focusing on your immediate surroundings — what you see, hear, and feel — you can reorient yourself to the present and step out of that freeze or panic mode.

What about after the crisis? How do people process trauma once the immediate danger has passed?

After a crisis, some people experience relief and move on quickly, while others may develop symptoms of trauma over time. It can show up as hypervigilance, where they’re constantly on edge, or as avoidance, where they don’t want to think about what happened.

Trauma can also manifest physically, with people experiencing headaches, stomach issues, or fatigue.

This is why it’s so important to process trauma rather than suppress it. EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) is one therapy that has been effective in helping people process traumatic memories, allowing them to integrate those experiences in a healthy way.

You mentioned working with veterans and first responders. How does their trauma differ from civilian trauma?

Veterans and first responders often experience a different kind of trauma due to the nature of their work. They’re exposed to life-threatening situations repeatedly, which can lead to something called cumulative trauma. This happens when smaller traumatic events build up over time, creating a larger, more complex emotional burden.

Combat veterans, for example, might struggle with what we call “moral injury,” which occurs when they’ve had to make life-and-death decisions that conflict with their moral beliefs. First responders often face similar struggles, especially when dealing with loss or witnessing death regularly.

For both groups, trauma is often compounded by the expectation to stay strong and keep going, which makes it harder for them to ask for help when they need it.

What advice would you give to someone who’s experienced trauma but doesn’t feel ready to seek therapy?

Start small. It can be overwhelming to dive straight into therapy, especially if someone doesn’t feel ready to talk about their trauma. One option is to begin by focusing on self-care — getting enough sleep, eating well, exercising. These might seem like simple things, but they help build a foundation of resilience.

Another step is to educate yourself about trauma. There are books and resources that explain how trauma affects the brain and body, and that understanding can reduce some of the fear around addressing it. When you’re ready, start with a therapist who understands trauma and uses evidence-based techniques like EMDR or cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

Can you talk a bit more about mental preparedness in survival situations? How do people train their minds for that?

Mental preparedness involves cultivating the ability to stay calm and think clearly under stress. It’s not something that happens overnight, but it can be developed with practice. One way to train for this is through scenario-based exercises. These exercises force you to think through different emergencies in advance, considering what steps you’d take and how you’d handle them emotionally.

Another important part of mental preparedness is recognizing that fear and anxiety are natural responses in survival situations. It’s not about eliminating those feelings but learning how to manage them, so they don’t take over. Techniques like mindfulness, sensory grounding, and controlled breathing help you keep your emotions in check. You want to get to a place where, even though you feel fear, it doesn’t stop you from making smart decisions.

Finally, maintaining a positive mindset is key. People who survive extreme situations often talk about the importance of staying hopeful, even when the odds seem stacked against them. If you allow despair to take root, it can be paralyzing. Staying focused on small, actionable steps — like finding water, shelter, or contacting others — keeps you moving forward and engaged in the process of survival.

What are some other mental traps people fall into during survival situations, and how can they avoid them?

One of the biggest mental traps is tunnel vision. In a crisis, people often get fixated on one problem and lose sight of the bigger picture. For example, they might focus all their energy on finding food while neglecting shelter or security. Tunnel vision narrows your focus to the point where you miss critical details that could make the difference between life and death.

To avoid this, you need to constantly assess and reassess the situation. Ask yourself: What’s the most immediate threat? What resources do I have? What’s my next move? Flexibility in your thinking is key. Instead of rigidly sticking to one plan, be willing to adapt as circumstances change.

Another trap is the “freeze” response, where people become so overwhelmed by fear or uncertainty that they do nothing at all. This can happen when you’re faced with a decision that feels too big or too risky, so you end up paralyzed. The way to counteract this is to focus on taking small, manageable steps. Even if you don’t know what the best long-term solution is, doing something — anything — can help break that freeze. For example, if you’re lost in the wilderness, start by finding water or building a shelter. Those small actions give you a sense of control and momentum, which can help you get unstuck.

Finally, there’s the trap of giving up too soon. When people feel like there’s no hope, they often stop trying altogether. But history has shown us time and time again that the human body and mind are capable of incredible feats of endurance. It’s often the people who keep pushing forward, even when they’re tired, hungry, and scared, who end up surviving. It comes down to mental grit — believing that you can make it, even when things seem bleak.

In your experience, how does a community respond to disasters, and what role does that play in recovery?

Communities play a vital role in both surviving and recovering from disasters. When a crisis hits, people naturally turn to their neighbors for help, and that mutual support can make all the difference. During a disaster, resources may be scarce, and government or emergency services can be overwhelmed. In those moments, having a tight-knit community where people look out for each other can literally be lifesaving.

In the immediate aftermath, communities that come together tend to recover faster. You see this time and again. After hurricanes, wildfires, or floods, it’s the neighbors helping neighbors that provides the first line of support. Whether it’s sharing supplies, clearing debris, or checking in on vulnerable individuals, that community resilience makes a huge impact.

Long-term, a supportive community can help with the emotional recovery from trauma as well. Disasters can take a toll not just physically, but mentally and emotionally. Being part of a community that shares the burden and works toward recovery together can help individuals process their experiences and start to heal. There’s something powerful about not going through it alone.

What are the toughest psychological challenges you’ve seen in trauma survivors that also appear in extreme survival situations?

So, when we talk about trauma survivors, whether it’s civilians affected by a disaster or a soldier hit by an IED, some of the psychological challenges are remarkably similar. The main issue we see is when trauma gets “sticky.” That’s our slang for when the event doesn’t fade into just a bad memory, but instead lingers and becomes something that stays with you.

Often, there’s a connection to a “touchstone event” in their past — either a previous trauma or a violation of a core belief. For example, someone who survived a house fire at a young age might attach what we call a cognitive stuck point. This is when your brain makes an assumption that isn’t necessarily true, but you believe it. Stuck points could be things like “the world isn’t safe” or “it’s my fault.” These stuck points create a mental file in your brain, and every time you experience something that triggers that feeling, it adds to the file.

So, for someone who survived a fire as a child, hearing their boss raise their voice might trigger the same feeling of not being safe, even though the situations are totally different. This accumulation of experiences can lead to intense reactions, whether it’s anger, anxiety, or avoidance. The more trauma you accumulate, the more these triggers show up in unexpected places — fireworks, crowded rooms, even smells.

Once you find that event that created the “file,” what happens next in therapy?

Once we identify that touchstone event, we have a few options. In my case, I use EMDR, which helps desensitize the memory and change how the brain processes it.

EMDR stimulates both hemispheres of the brain, generating a lot of neural activity. This allows us to access old memories with more clarity and create new neural pathways. During EMDR sessions, I’ll ask the patient to think about that traumatic event for short intervals — 15 seconds or so — and then I’ll check in with them. It’s intense, but we do it in small, manageable doses.

As we work through the memory, I ask questions that challenge the patient’s stuck point. For instance, if a soldier feels it was his fault that a buddy got hurt, I’ll ask questions like, “How responsible should a 4-year-old (or a soldier in a chaotic war zone) really be for that situation?” Gradually, this helps them reframe the event and adopt a healthier perspective. The memory doesn’t disappear, but the way they think about it changes. Over time, this can significantly reduce symptoms like nightmares and flashbacks.

How can someone balance staying prepared without falling into the trap of constant worry or paranoia?

It’s easy to get addicted to what we call “doom porn” — constantly consuming disaster news or staying in prepper forums and Facebook groups. It can activate your stress response, which might even feel good on a small scale, like a hit of adrenaline. But that’s not sustainable.

Prepping should alleviate anxiety, not create more.

For beginners, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed or like they need to “catch up” with others who have more gear or skills. That’s a dangerous mindset because it can lead to burnout and even financial trouble. Focus on the basics first: water, food, first aid, and building a solid pantry. Don’t go into debt trying to buy the best gear overnight. Prepping is a slow, steady journey, and you should take it step by step.

Are there any misconceptions about trauma therapy or survival psychology that you encounter frequently?

One misconception I often run into comes from the 1970s when a lot of Vietnam vets came back, and we didn’t do a great job of taking care of them. There’s this belief that PTSD is a lifelong, debilitating condition, but it doesn’t have to be. PTSD is just one of several trauma diagnoses, and it’s the one most people are familiar with. But we’ve come a long way in identifying the causes of trauma and finding ways to resolve it.

What we aim for is something called “adaptive resolution.” That’s when the brain accepts a traumatic memory as just a bad memory — it was a terrible experience, but the person comes to terms with it. They realize, “I did the best I could to survive that,” and the memory gets filed away like any other unpleasant experience, rather than staying as a trauma memory that keeps haunting them.

Are there any books or resources you recommend for people dealing with trauma or those interested in survival psychology?

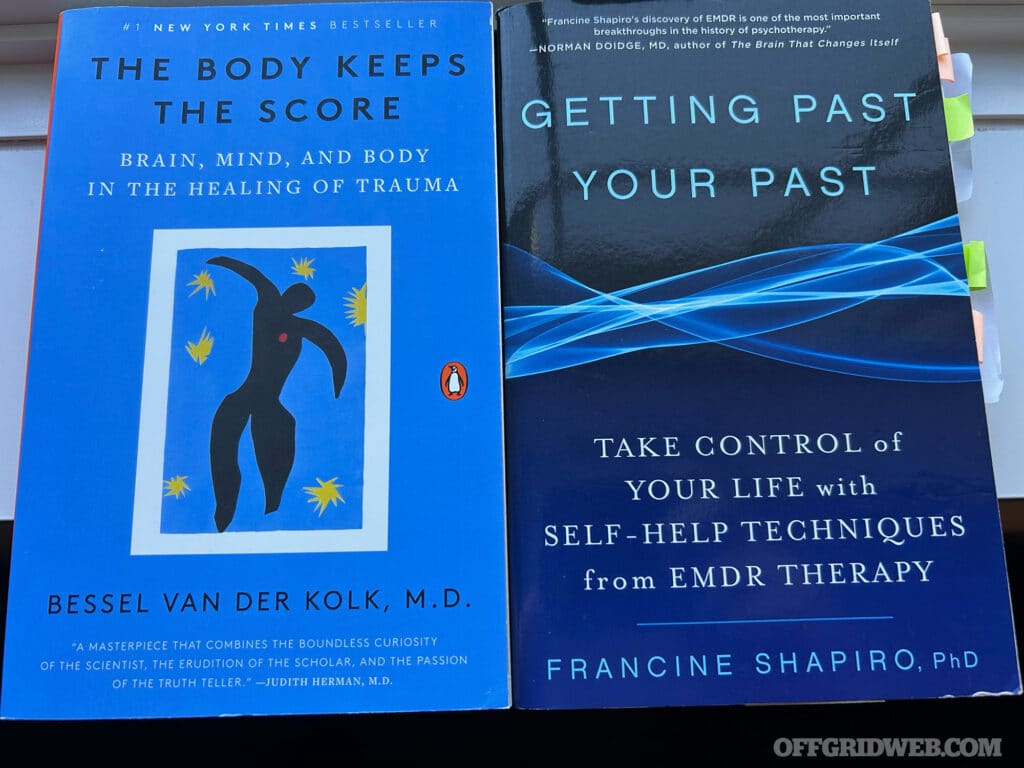

I recommend The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel van der Kolk. It’s a fantastic book that helps people understand why they feel the way they do after experiencing trauma. It dives into why things like nightmares, flashbacks, panic attacks, and other symptoms happen and how trauma is stored in the brain.

Another one is Getting Past Your Past by Francine Shapiro, who created EMDR therapy. It’s an excellent resource for anyone interested in learning more about trauma processing and therapy. But I’d suggest starting with The Body Keeps the Score — it’s very eye-opening for anyone trying to understand trauma on a deeper level.

Don’t miss essential survival insights—sign up for Recoil Offgrid's free newsletter today!

Check out our other publications on the web: Recoil | Gun Digest | Blade | RecoilTV | RECOILtv (YouTube)

Editor's Note: This article has been modified from its original version for the web.

STAY SAFE: Download a Free copy of the OFFGRID Outbreak Issue

STAY SAFE: Download a Free copy of the OFFGRID Outbreak Issue

No Comments