RECOIL OFFGRID Survival Between River and Sky: Recounting a Jungle Expedition

In This Article

Embers from the fire glowed like the eyes of some ancient animal, watching from the shadows. A few candles guttered in the damp air, their halos of light swaying whenever a breath of wind slipped through the gaps in the canopy. Beyond the circle of light, the jungle was a black wall, the hum of insects and frogs muffled by the stillness of the hour.

Beside me sat Quini, a Matis elder whose numerous piercings gave his face the fierce visage of a jaguar. He leaned forward, elbows on his knees, and spoke in a voice so soft I had to tilt my head toward him. His words moved in a rolling current of vowels and consonants that I didn’t understand, yet the rhythm alone carried a weight that pressed me to listen harder.

Phillip, an indispensable member of our expedition, translated the story in fragments as the interpretation unfolded. Quini was telling his story of first contact — of the day strangers came from beyond the forest. Some arrived with gifts, tools, and goodwill. Others came to take. His people had seen kindness and cruelty from the outsiders, sometimes within the same season, sometimes from the same hands.

Someone in our group asked how they were able to forgive some of the terrible trespasses committed against them. And then Quini spoke the line that has stayed with me since, “We did not judge the many by the evil of a few.”

For me, the words cut through the night like the crack of a branch underfoot. In a world quick to brand entire groups as guilty for the actions of a handful, that kind of grace felt almost revolutionary. I had come here to learn survival skills, but I was starting to realize that the deepest lessons in the jungle weren’t about shelter, fire, or food.

Ticuna tribesman, Alberto, makes living in the jungle look like a walk in the park. His tutelage throughout the expedition was always enlightening. (Photo Credit: Phillip Irizarry)

It was impossible to imagine that moment when I first set out from home.

The floor of Bogotá’s El Dorado International Airport was cold against my back as I tried to stretch out between a wall and my pack. It was just after midnight, and around me, other travelers lay draped across their luggage, arms and shoes tucked under straps as makeshift security. I had a handful of hours to catch a few winks before my connecting flight to Leticia. Sleep came in scraps, broken by the crackle of the PA system and the rolling clatter of carts on tile. Before long, I was up and meeting the rest of my expeditionary group in the security line. We had been cobbled together by Bushcraft Global, an outfitter with the right connections in Amazonia to make this kind of adventure happen.

Peter Magnin, a jungle veteran who has been on over a dozen trips like this, introduces himself to us as our main guide.

By the time I boarded our connecting plane south, the morning light was rising over the horizon. From the window, Bogotá’s sprawl quickly gave way to open land, then to an unbroken carpet of green that stretched in every direction. The rivers below cut through it in wide brown arcs, the sunlight catching the surface like strips of tarnished copper.

Leticia sits where Colombia meets Brazil and Peru, a border city that can’t be reached by road. Disembarking the plane, the air was thick and warm the moment I stepped onto the tarmac. The greenhouse scent of damp earth mingled with the exhaust of motorbikes buzzing through the streets. Our group assembled at the Tanimboca Nature Reserve, a few kilometers outside the city. Here we got to know Goran, owner of the reserve, whose main goal is bridging our world with the one we were about to enter.

The first two days were for acclimation. We stayed in palm-thatched cabins elevated on stilts, the screen walls keeping out most — but not all — of the night’s curious visitors. Spider monkeys chattered from the branches above, their tails swinging like pendulums as they eyed us from a safe distance.

Matis elder, Quini, demonstrates how to set a spring trap large enough to catch a taipan. (Photo Credit: Mike Condict)

We trained in the canopy that first day, climbing a rope to a platform 30 meters above the forest floor. From there, zip lines and rope bridges carried us between trees until we descended again by belay. The air up there was different, less dense, but still hot enough to stifle the lungs with each breath. Every muscle worked harder in the humidity, every drop of sweat refusing to evaporate. That was the point though, to teach our bodies what they’d be working against in the days to come.

That night, we hiked into the forest with a Witoto guide who showed us his “jungle EDC:” a small knife, headlamp, and several small pouches containing mambé, a powdered coca leaf mixture taken to sharpen the mind and, in his tradition, to honor the jungle. In the light of our headlamps, the forest revealed itself in pieces: the jewel-toned body of a tree frog clinging to a leaf, the eerie green glow of a scorpion under ultraviolet light, the jointed legs of a wandering spider disappearing into shadow.

On the second day, we wandered the markets of Leticia, buying machetes and fishing spears. Locals smiled when we tried our limited Spanish, often correcting us gently with a laugh. By evening, the indigenous members who would accompany our group had arrived from upriver: Victor, a representative of the Ticuna tribe; Quini, a Matis tribal elder; Tupa, a gifted Matis craftswoman; and her preteen son Tumi. Under Victor’s guidance, we shared our first rapeh ceremony together, the herbaceous powder burning through my sinuses like a fuse, clearing my head in a rush of light and heat. Quini’s smile afterward told me that joining their customs from the start meant more than I understood at the time.

The next morning, the roads ended. The jungle began.

The truck dropped us off at a rough track that ended in tangled undergrowth. We linked up Alberto of the Yucuna tribe who would be graciously hosting all of us on his tribal land. Juaneho Cuéllor, our camp cook for the next eight days, was there as well. Last-minute gear was stowed, packs were shouldered, and we began the three-hour hike into the interior.

It was slightly cooler beneath the triple canopy, but not by much. The heat was the kind that presses down on your shoulders and seeps into your bones. Humidity wrapped itself around me like a wet blanket. My clothes clung to my skin within minutes. The air smelled of leaf litter, loam, and the faint sweetness of something flowering nearby.

Talented Matis craftswoman, Tupa, and intrepid traveler Michael Burkus, share a laugh while making pottery from river clay. (Photo Credit: Phillip Irizarry)

The soundscape shifted as we went deeper. What little noise pollution existed this far from Leticia quickly faded, replaced by the rasp of insects and the occasional throaty call of a bird I couldn’t name. Sounds traveled surprisingly far, and our native guides spoke quietly to avoid disturbing the peace. Every so often, the path narrowed to the point where we had to turn sideways, pushing through vines that clung to the fabric of our clothes.

A Yucuna village emerged from the forest where the air smelled of woodsmoke and roasting cassava. Surrounding the village, large gardens were planted in the shade of young trees, the result of slash-and-burn cycles timed to the forest’s rhythm. Alberto pointed out crops tucked beneath the canopy, shielded from the equatorial sun until they were ready to thrive on their own.

By the time we reached the river bend that would be our camp, my legs felt heavy but alive. Hammocks went up between trees, each with its own tarp roof. A tributary snaked past, its surface dimpled by insects, hiding stingrays, caiman and otters beneath.

That first night, under the triple canopy’s darkness, I saw the forest floor glowing. Fallen leaves had been colonized by bioluminescent fungus, each emitting a pale green light. It was like standing above a second night sky, stars scattered at my feet.

Founder of the Tanimboca Nature Reserve, Goran, was our liaison between city and jungle. None of this would have happened without his expertise.

Peter showed us how to swing a machete so the blade did the work instead of our shoulders. He made us practice until the motion was clean and efficient. Quini introduced us to the medicinal plant achote, smearing the cool red paste across our faces. It carried the faint scent of fresh earth and stained the skin until the next wash.

Alberto led us upriver to gather materials: black palm for blowgun barrels, palm leaves for weaving, and burro vines for lashings. He found palm heart in the wild, slicing it free with a practiced hand and passing around the tender, coconut-flavored core. Quini found a resin, quick to catch fire, and capable of many other uses.

Back in camp, Tupa taught us to weave baskets from palm fronds. Her hands moved with effortless precision, each strip folding over the next in steady rhythm. She also guided our group through the days-long process of making pottery from mud found near the edge of the river. Alberto mentored the group on how to construct a Yucuna-style blowgun, sew machete sheathes from tree bark, and creating simple-but-effective fishing bows.

Each night, the river called us back, sometimes for bathing, sometimes for fishing. Spear fishing in the dark was nerve-wracking. The riverbank was slick, stingrays could be underfoot, and occasionally the beam of a headlamp would catch the gleam of caiman eyes.

The jungle rewarded patience. Move too fast and you missed everything that mattered.

While our group was out exploring the jungle, Juaneho ensured everyone was well fed when we returned to camp. (Photo Credit: Phillip Irizarry)

Rituals came without fanfare, woven into the fabric of each day.

Rapeh was the most frequent, a reminder to clear the mind and align intention before entering the forest. For me, it felt like a mental sharpening stone, stripping away the fog.

Dressed as the “Mariwin,” a forest demon, Quini would be nearly invisible if not for the red clay mask disguising his face.

The Sanaga ceremony, an eye-drop made from another important medicinal plant, came before a hunt. The root tincture burned so intensely I had to clench my jaw, blinking against the tears. In that moment, I was instructed to speak the traits I wanted during the upcoming hunt: the sharp gaze of a hawk, the patience of an anaconda, the ferocity of a jaguar. When the burn eased, the forest looked as if someone had adjusted the contrast, colors richer, shadows deeper.

On our penultimate day, Quini emerged from the tree line transformed, skin blackened with charcoal, red clay mask, ferns tied to his limbs. He was dressed as the “mariwin,” a demon of the forest. In silence, he struck each of us with palm spines until they broke the skin. The sting was immediate, but so was the surge of energy that followed. In their villages, this was performed on a regular basis, for children, elders, everyone. Pain was a teacher, and the lesson here was that the mind could overcome the fear of it.

Some marks were permanent. On one morning, we were given the option of receiving a tattoo, ink made of charred resin, dual palm spines the needle. I chose to accept it, three simple lines, a symbol of acceptance into this close-knit group of travelers.

In Alberto’s “moloca” — a large palm thatched building for the tribe to gather — a tuxedo cat wound around my legs as I stood in the building’s cool shade. I knelt to scratch its head, and a small Yucuna girl joined me. She said nothing, just smiled, her tiny hand brushing the cat’s fur alongside mine. We didn’t need translation for that moment.

Getting a Matis tattoo was an option that some of us took advantage of. We received the tat on our arms, but the Matis typically have them on their cheeks and foreheads.

Around the fire, conversations ebbed and flowed in interesting directions. A question in Spanish answered in Portuguese, translated into English, then back again into Portuguese or Matis. We laughed as much at the misfires as at the jokes.

One night we ate stingray, its meat tender and salty, like pulled pork from the river. Another day brought grilled grubs, their outer skins crisp, the inside nutty and rich. On our last morning Alberto had harvested a small caiman from the river for breakfast. I learned that in the jungle, trying something new wasn’t only about the experience, it was also a sign of trust.

Above: Creatures, like this scorpion, that would be next to impossible to see under the illumination of a headlamp, show themselves in stark contrast under a UV light. (Photo Credit: Jamie Boggs)

Danger shapes the common Western view of the jungle — snakes that can kill with a single bite, insects that spread disease, predators lurking in the water. Those threats exist, but they’re not the whole truth.

Rather than unmitigated chaos, the jungle is order of a different kind. Every plant, every animal, every sound has a place and a meaning if you’re willing to learn it. The people who thrive there move through it with an awareness that most of us never develop. They don’t rush. They don’t force. They wait for the right moment because they know the wrong one can be fatal.

I learned that lesson firsthand on the riverbank at night, spear in hand. The mud was slick, the water hiding all manner of dangers under the silt. One misplaced step could have meant serious injury. My instinct was to move quickly, to cover more ground, but I forced myself to slow, placing each foot deliberately. When I matched the pace of the locals, I began to see more — the shimmer of fish just under the surface or the wandering spider lurking near the bank.

Our primary guide, Peter Magnin, stands triumphantly over a freshly caught stingray. It made for a tasty dinner!

Even as someone with a background in survival and preparedness, I realized that my training had been built around goals: Find water, build shelter, make fire. Here, the goal was to exist within the environment without breaking its rhythm. That mindset shift is one I’ve carried home, because it applies everywhere. Rushing is rarely the best way forward.

Technology is inexorably changing that relationship. Starlink dishes and cell phones are appearing in villages that once communicated only by runner or river. Younger generations leave for cities, trading the knowledge of their elders for the speed of modern life. These cultures are still here, still vital, but the window to learn from them firsthand is narrowing.

Leaving the jungle wasn’t a clean break. We packed camp in the morning under a sky heavy with the first real rain of the trip. It fell in steady sheets, drumming on the tarps and splashing into the river. Goran tells us the jungle is sad that we are leaving. Hiking back to the road took half the time of our journey in, our bodies had finally adapted to the heat and humidity. Still, stepping into open ground felt strange after days under the canopy.

The truck that picked us up stopped at a roadside shop where chilled beer waited in sweating cans. It was the first cold drink we had in over a week, and it tasted like victory. Back at Tanimboca, we had lunch and said goodbye to our indigenous guides. Before we went our separate ways, through Phillips’ translation, Quini said, “Because of airplanes, the distance between us isn’t that far. We’ll always be just a few hours away.” It was a bittersweet moment that punctuated just how kindly we had been treated by our hosts over the course of the trip.

Villagers assist us as we toast coca leaves to make mambé, a ceremonial mix of herbs used to honor their ancestors and the jungle itself. (Photo Credit: Jamie Dakota aka “Chuii”)

That evening, we went into Leticia to watch the green parrots. Thousands of them fly in from the jungle at dusk every single day at the same time, filling the trees in the central park with a living, chattering canopy. From there, we wandered into the Three Frontiers festival that just happened to be taking place at the time. Street vendors sold grilled meats, fried plantains, and ice cream. Music spilled from every corner.

The next day, we took a boat up the Amazon River to Monkey Island. Along the way, we spotted gray dolphins leaping through the current, and — if I wasn’t mistaken — the rolling pink back of a river dolphin breaking the surface.

On our last night, Goran hosted a farewell feast at the Reserve. Juaneho prepared Colombian barbecue, smoky and rich, while locals performed traditional dances to the beat of exciting music. The air was thick with the smell of food, drinks, and the raucous sounds of new friends sharing their most exciting moments of the trip.

Saying our goodbyes was more than a farewell. It was a reminder that closeness isn’t measured in miles, but in shared moments, mutual respect, and the willingness to step into each other’s worlds without judgment.

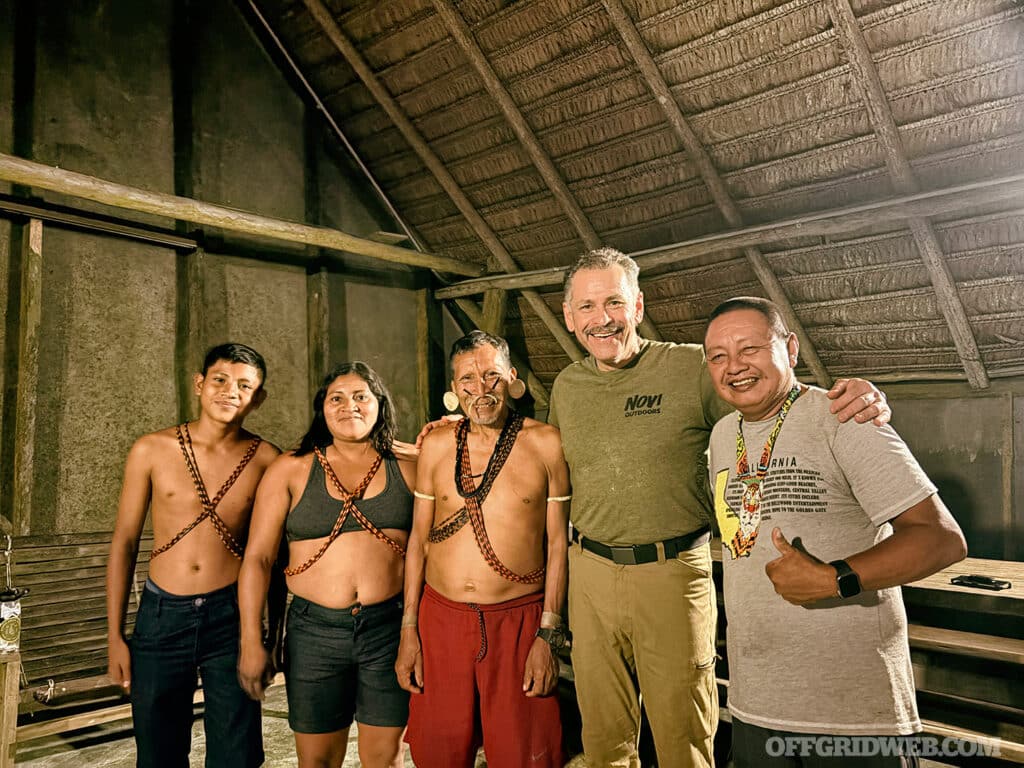

From left to right: Tumi, Tupa, and Quini of the Matis; adventurer and elected expedition interpreter, Phillip Irizarry; Ticuna tribesman and Tanimboca guide, Victor. All of whom helped make this expedition unforgettable. (Photo Credit: Phillip Irizarry)

If you’ve ever dreamed of pushing past the edges of your comfort zone, of learning survival not from books, but from people whose lives are woven into the land itself, you don’t have to imagine it. This journey was made possible by Bushcraft Global and the Tanimboca Nature Reserve, two teams dedicated to connecting people with the wild in ways that are authentic, challenging, and transformative. These organizations not only teach modern adventurers the skills to thrive in extreme environments, but also ensure that the traditions, stories, and techniques of those communities are respected and preserved.

For me, this trip began as a survival adventure and ended as something far deeper.

It quickly became a lesson in humility, patience, and reciprocity. For anyone willing to take the leap, the Amazon is still there, waiting to teach. Some lessons you can’t learn in books, on screens, or in classrooms. Some truths only reveal themselves in the glow of a dying fire, in the soft-spoken language of an elder, deep in a green cathedral that has endless wisdom to share.

Don’t miss essential survival insights—sign up for Recoil Offgrid’s free newsletter today!

Check out our other publications on the web: Recoil | Gun Digest | Blade | RecoilTV | RECOILtv (YouTube)

Editor’s Note: This article has been modified from its original version for the web.

STAY SAFE: Download a Free copy of the OFFGRID Outbreak Issue

STAY SAFE: Download a Free copy of the OFFGRID Outbreak Issue

No Comments