RECOIL OFFGRID Survival Cold Water Safety: Avoid Common Mistakes in Freezing Temperatures

In This Article

Water features such as lakes and oceans tend to vary in temperature based on latitude and depth. Even Caribbean Sea bottoms near the equator can reach temperatures as low as 36 degrees F. Luckily, humans rarely venture that deep. Rapid immersions in cold water, however, are still dangerous and can quickly become life-threatening if not prepared. Let’s discuss what you can do to increase your chances of survival.

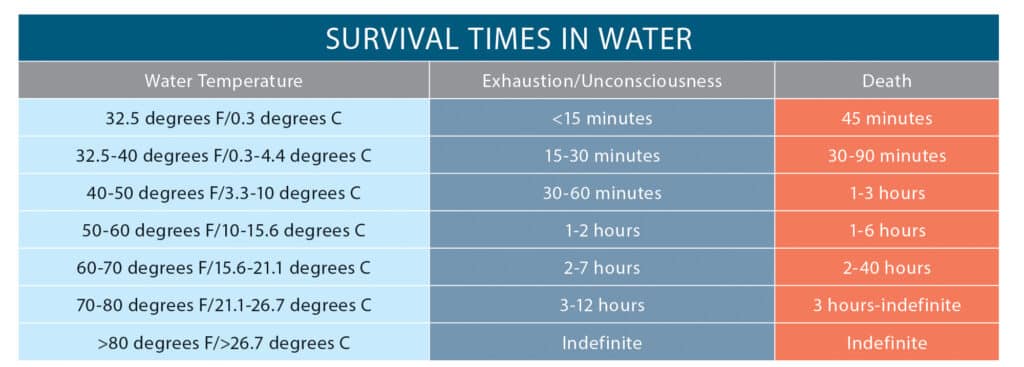

If water temperatures remain above 70 degrees, a victim may survive quite a while. Once below 68 degrees, survival is unlikely beyond a certain time limit. Even less time exists before exhaustion leads to an inability to remain conscious. To an extent, this varies according to the circumstance and from individual to individual. You could die of hypothermia off a tropical coast if immersed long enough. Body size and build, fat content, clothing, flotation aids, and even psychological makeup play a part.

Above: Cold water survival chart.

The ill effects of exposure to cold are called “hypothermia.” Hypothermia occurs when body temperature drops below 95 degrees F (35 degrees C). When exposed to cold, the body’s muscles shiver to produce heat. This functions only to a point, after which the victim may appear confused and uncoordinated; as the condition worsens, speech becomes slurred, and the patient will become lethargic and uninterested in helping themselves; they may fall asleep. This occurs due to the effect of cooling temperatures on the brain; the colder the body core gets, the slower the brain works. As hypothermia progresses, organs fail, and the victim expires.

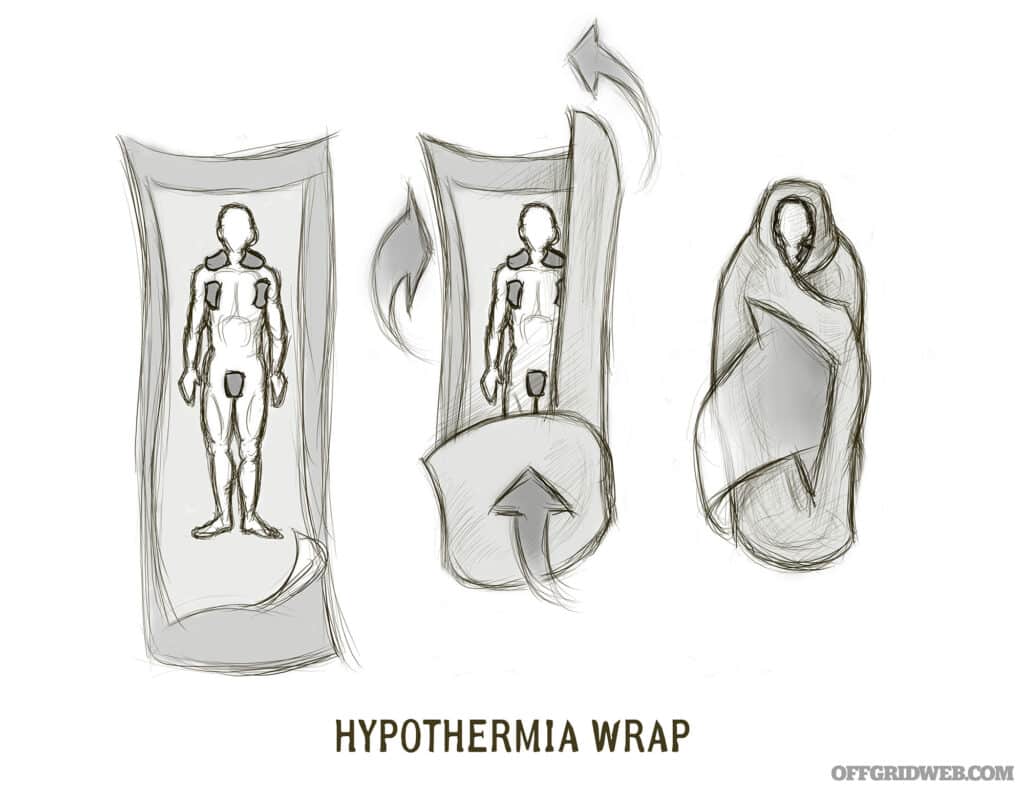

Those suffering from general hypothermia must be removed from the cold and warmed immediately. If the victim must remain on the ground, place a barrier underneath and cover with warm blankets.

Above: Typical hypothermia wrapping technique.

If they can’t be moved to a warm place indoors, place warm dry compresses in the neck, armpit, and groin regions. These are areas where major vessels come close to the body surface and can move warm temperatures to the body core more efficiently. Warm fluids may be given to those who are awake and alert but may be dangerous in those who have altered mental status. Although controversial in some circumstances, a rescuer might “spoon” with the patient and cover with blankets to share body heat.

Assume that anyone encountered in cold weather with altered mental status is hypothermic until proven otherwise.

The body loses heat to the environment whenever the ambient (surrounding) temperature is lower than about 68 degrees F. Much lower temperatures cause heat to radiate away more quickly. This happens in water more rapidly than in air due to its increased denseness. As such, when the body’s surface comes in sudden direct contact with cold water, it conducts heat from the body many times faster than cool air.

Above: Always wear a life jacket while boating, especially on large bodies of water.

Events that involve a rapid immersion in cold water include capsizing boats, going overboard in storms, and even falls through the ice during winter hikes. All of these could lead to fatal consequences if the victim fails to act rapidly to mitigate the risk of drowning and hypothermia.

If your boat sinks and you find yourself in cold water, you’ll need a strategy that’ll keep you alive until you’re rescued. Failure to follow this advice decreases the amount of time you have before the effects of hypothermia take hold:

Wear a life jacket. Whenever you’re on a boat, wear a life jacket. A life jacket can help you stay alive longer by 1) enabling you to float without using a lot of energy and 2) by providing some insulation. Jackets with built-in whistles or a beacon light are best, so you can signal that you’re in distress.

Above: A sudden dunk into cold water initiates a “gasp reflex.”

Keep your clothes on. While you’re in the water, don’t remove your clothing. Button or zip up. Cover your head if at all possible. The layer of water between your clothing and your body is slightly warmer and will help insulate you from the cold. Remove your clothing only after you’re safely out of the water. Then, do whatever you can to get dry and warm.

Get out of the water, even if only partially. The smaller the percentage of your body exposed to cold, the less heat you lose. Climbing onto the hull of a capsized boat or holding onto a floating object will increase your chances of survival, even if you can only partially get out of the water.

Position your body to lessen heat loss. Use a body position known as the Heat Escape Lessening Position (think H.E.L.P.) to reduce heat loss while you wait for help to arrive. Just float and hold your knees to your chest; this will help protect your torso (the body core) from heat loss.

Huddle together. If you have fallen into cold water with others, keep warm by facing each other in a tight circle and holding on to each other.

Above: Groups in cold water should huddle together while facing each other.

Don’t use up energy. Unless you have a dry place to swim to, do not exhaust yourself swimming.

In many parts of the country, lakes freeze to the point that it may be difficult to identify a safe trail to hike. Indeed, a field of newly fallen snow may camouflage a water feature with a thin coat of ice.

Above: After a snowfall, you might not even know you’re walking on lake ice.

Ice must be at least 4 inches thick to handle the weight of an average human. Having said that, this “safe” thickness may be undermined by flowing water just below the surface, which weakens the underside of the ice. Safety is never guaranteed when it comes to walking on the ice.

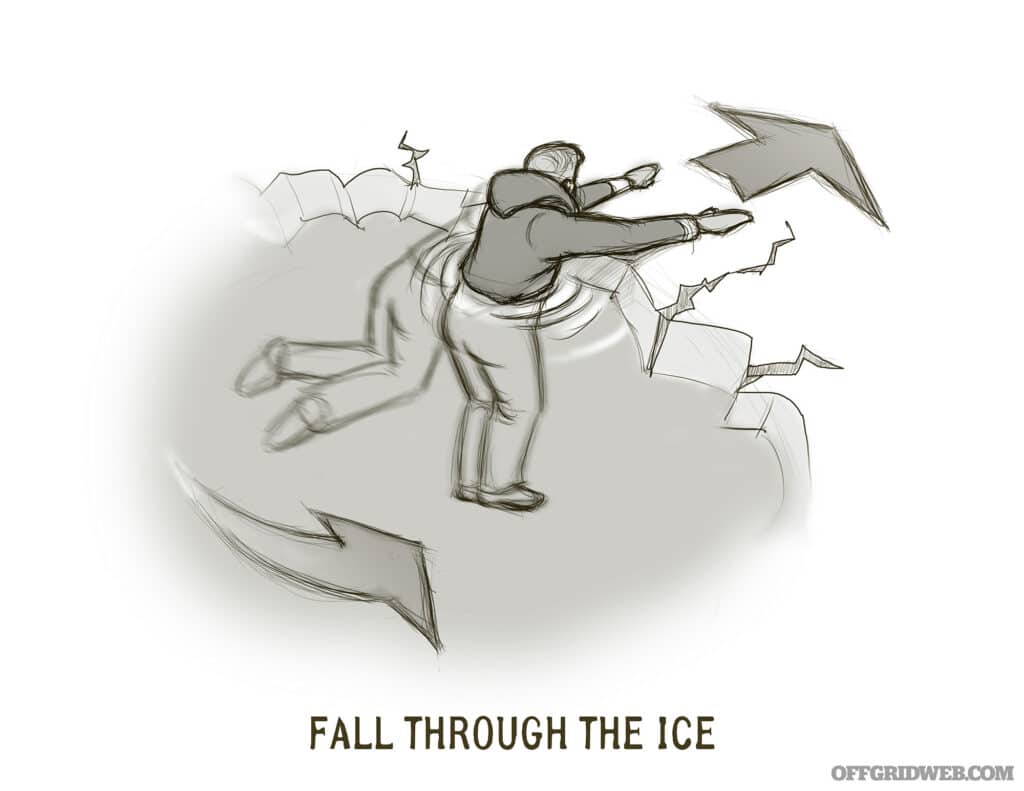

If you end up on thin ice and fall through, your body will react to the sudden immersion in cold water with an increased pulse rate, blood pressure, and respirations. This is known as the “cold shock response” (also called the “gasp response”). Drowning can occur as your body reflexively takes a breath and hyperventilates as you go underwater. Life-threatening cardiac events can also occur due to the sudden increased workload on the heart. Both are common causes of death in these situations.

Although this situation is difficult without a rescuer with rope or other equipment, it’s important to make every effort to keep calm. You still have a few minutes to get out before you succumb to the effects of the cold. Your main enemy here is panic.

If it’s possible, place your hand tightly over your nose and mouth as you go under. This will minimize the amount of water you inhale with the cold shock response. Then, get your head above the water by bending backward and, once in the air, taking a deep breath.

Tread water and quickly get rid of any heavy objects that might be weighing you down. Keep your clothing on, however; there are air pockets between layers that are helping you stay buoyant.

Now, turn in the direction where you came from; the ice was strong enough to hold you there. With any luck, it still is.

Spread your arms on the surface of the ice. If you have an ice pick (a useful item for anyone hiking on the ice), dig it into the ice as a handhold for support. Then, try to lift out of the ice while kicking your feet to get some forward motion. At the same time, try to get more of your body out of the water.

Above: Spread your arms on the surface of the ice.

Lift a leg onto the ice and roll out onto the firmer surface. Do not stand up, though — you’re not out of danger. Keep rolling in the direction that you were walking before you fell through. This will spread your weight out, instead of concentrating it on your feet. Then, crawl away until you’re sure it’s safe.

Start working to get warm immediately. The wisest hikers will have a change of clothes in a waterproof container available. This allows you to always have something dry to wear if you get wet. Other important items include a fire-starter; get one that works even if wet.

When it comes to predicting the safety of walking on ice, the color may give you a clue as to safety:

Light gray or black ice – This is a sign of melting, weak ice, even in freezing temperatures. Ice can melt even if the air temperature is below 32 degrees F (0 degrees C). This ice will not hold your weight.

Above: Black ice won’t hold your weight.

Mottled or slushy ice – Thawing ice which may appear thick might be mottled in color. This ice may be deteriorating in its center and base. Consider it unsafe for walking.

White or opaque ice – This ice may be caused by snow thawing and refreezing in layers. Porous air pockets in-between usually indicate a questionable ability to hold weight.

Bluish-clear ice – Ice that is high density and strong is often bluish-clear in color. It is the safest ice to be on if at least 4 inches thick.

Above: Blue ice is considered to be strongest.

Areas of contrasting colors indicate an uneven thickness and should be avoided. Larger bodies of water take longer to freeze, and saltwater usually needs colder temperatures, depending on the concentration of salt and other factors (28 to 29 degrees as opposed to 32 degrees F).

It’s important to understand that survival rates are higher when traveling in groups. If walking on a frozen lake, members should always proceed in single file and be separated by several yards. This will guarantee potential rescuers are at hand if someone falls through the ice.

Above: Just because its cold outside, doesn't mean you have to be uncomfortable.

When it comes to preventing cold-related injuries, it’s useful to remember the simple acronym C.O.L.D. This stands for Cover, Overexertion, Layering, and Dry:

Cover: Protect your head by wearing a hat. This will avoid the loss of body heat from your head. Instead of using gloves to cover your hands, use mittens. Mittens are more helpful than gloves because they keep your fingers in contact with one another, conserving heat.

Overexertion: Avoid activities that cause you to sweat a lot. Cold weather causes you to lose body heat quickly; wet, sweaty clothing accelerates the process. Rest when necessary and frequently self-assess for cold-related changes. Pay careful attention to the status of elderly or juvenile group members. Diabetics are also at high risk.

Layering: Loose-fitting, lightweight clothing in layers do the best job of insulating you against the cold. Use tightly woven, water-repellent material for wind protection. Wool or silk inner layers hold body heat better than cotton does. Some synthetic materials, like Gore-Tex, PrimaLoft, and Thinsulate, work well also. Especially cover the head, neck, hands, and feet.

Dry: Keep as dry as you can. Get out of wet clothing as soon as possible. It’s very easy for snow to get into gloves and boots, so pay particular attention to your hands and feet.

Joe Alton, MD, is a physician, medical preparedness advocate, and three-time Book Excellence Award-winning author of The Survival Medicine Handbook: The Essential Guide For When Help Is Not On The Way. He’s also an Advanced Wilderness Expedition Provider and member of The Wilderness Medical Society. His website has over 1,200 articles, podcasts, and videos on medical preparedness.

STAY SAFE: Download a Free copy of the OFFGRID Outbreak Issue

STAY SAFE: Download a Free copy of the OFFGRID Outbreak Issue

No Comments