RECOIL OFFGRID Survival Spy Week with Jason Hanson: Survival Lessons from a Former CIA Officer

In This Article

You’re standing in line at a crowded consulate in a foreign country when you get a sinking sensation that you’ve been flagged to be detained. As you begin to slink away toward the lobby, an agent calls out to you. You calmly and deliberately take stock of your situation, noting several Marines posting security and another agent readying handcuffs. You stop and raise your hands to a surrender position, which appears submissive while also being an effective fighting position.

Your eyes continue to scan as you’re surrounded by three men — a Marine and two in suits. As the Marine places his hand on your shoulder, you control him with a wrist lock, strike one of the others in the throat, elbow the Marine, and kick the other one again. You block an attack by the Marine and shove him back into the third man, who has drawn his service pistol. You quickly disarm him and throw him to the ground. As horrified and petrified onlookers scream and scatter, you’re off to the races.

If this is your idea of what being a spy is like, then you probably already recognize this piece of fiction as the U.S. Embassy scene from the action movie The Bourne Identity. In reality, the life of an intelligence officer can be quite mundane at times and thrilling at others, but the stakes are no less critical. In the interests of national security, a CIA officer may perform counterintelligence, conduct surveillance, recruit agents, or protect personnel and assets. They operate in dangerous and nonpermissive environments, persuade and cajole, evade capture, and are ready for anything.

While the likelihood you’ll need to do dead drops or fight assassins is pretty low, many skills and tactics from the world of espionage are directly applicable to everyday life. We attended a weeklong course, dubbed “Spy Week,” taught by former CIA officer Jason Hanson. After a stint as a police officer in Virginia, Hanson joined the CIA and served for seven years, mostly overseas, before leaving to focus on his family. He then did training and corporate work, reaching wider acclaim after appearing on the TV show Shark Tank in 2014 and securing a deal with celebrity investor Daymond John. Since then, he’s published several books, appeared on numerous TV shows, and expanded his training offerings.

Titillating title aside, Hanson’s Spy Week course was chock full of practical and useful skills. Read on for five key lessons we took away from this experience.

The best way to survive a life-threatening, dangerous situation is to avoid it in the first place. At Spy Week, Hanson stresses that situational awareness — paying close attention to what’s going on around you — is the most important skill for you to practice on a daily basis. This is preached over and over again, including in this very magazine, yet you need only look around any public place to see scores of people obliviously hunched over their smartphones rather than observing the world around them.

If you have good situational awareness, you’ll have a better chance at noticing pre-incident indicators (known in layman’s terms as “clues”) of a potential threat. Someone staring at you unnaturally may have picked you out as a possible target. If someone is pacing you — matching your speed, whether on foot or in a car — this is very unusual as well. Criminals might also work together as a team, with one attempting to distract you while another sneaks up on you. A pair might attempt to funnel you between them to trap you; two people walking together don’t usually open up to let someone between them.

Above: Paracord, handcuff picks and shims, zip tie (cut by paracord), duct tape, and handcuffs.

Pay attention to baselines — what’s typical and normal for people and places. This will help you identify when something seems unusual. For a place, you might return home and notice some items moved or doors ajar that you know you always close — someone may have been or might still be in your home. For people, someone might be acting strangely, wearing inappropriate clothes for the weather, or paying too much attention to you.

Perhaps you suspect that someone’s following you. You can conduct what’s called a surveillance detection route, an oft-used skill in the intelligence business, to recognize if you’re being followed or targeted. For example, let’s say you’re a young woman in a department store and notice a man sneaking furtive glances at you, making you uneasy. To make sure you’re not just feeling paranoid, you could walk to another section, such as women’s handbags, and see if he eventually shows up. Then, go to another one on the opposite corner of the building or on another floor, perhaps women’s shoes. If he appears again, he’s probably following you, and you should contact store security. Similar concepts apply when you’re driving your car.

If you find yourself in the unfortunate circumstance of being abducted, first of all, fight like hell immediately. If criminals successfully snatch and relocate you, your odds of a good outcome drop significantly. The first 24 hours are critical; you’ll quickly lose energy, strength, and spirit as time passes and as you likely get sparse helpings of food and water. At Spy Week, Hanson advises that any chance you get, leave as much DNA behind as you can, particularly in spots that aren’t normally cleaned. For example, bite your lip and spit blood out behind some furniture or leave a bloody fingerprint under a table.

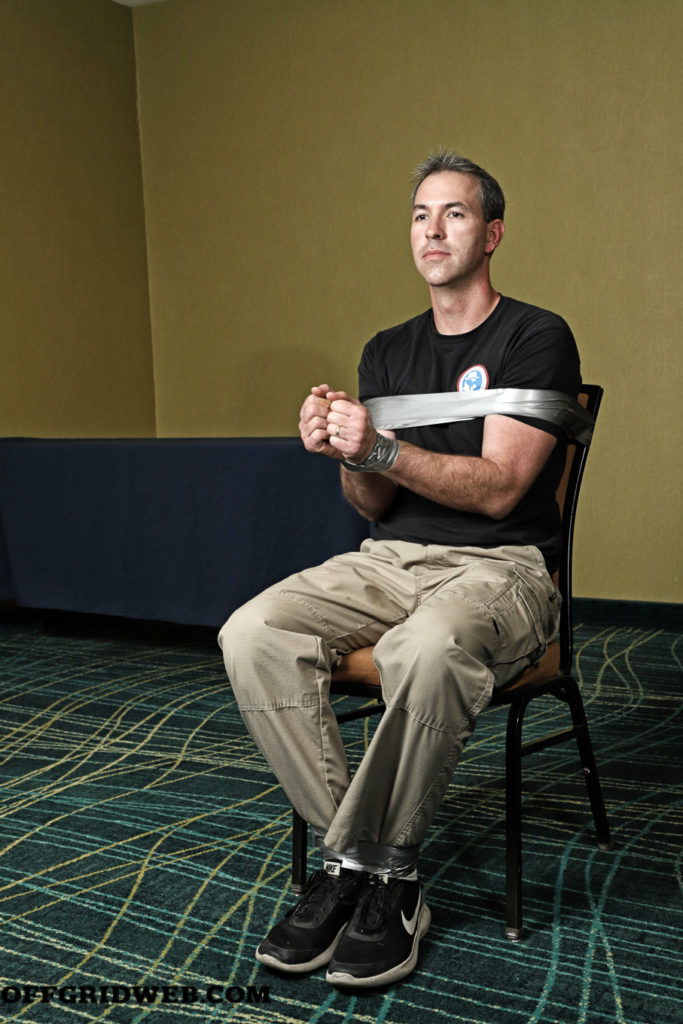

If you’re duct taped to a chair, jolt forward quickly, like you’re trying to put your head between your legs. If only one side of the tape around your chest breaks, spin your way out.

If you get an opportunity to escape, you may need to defeat restraints. Many victims feel psychologically crushed once they’re restrained; don’t despair, you can escape from many commonly used restraints.

Duct tape: This is one of the most prevalent restraints, as it’s cheap, easy, and readily available. Wrapping duct tape around someone’s wrists is quick and makes it easy to lead them around. Fortunately, duct tape is also easy to defeat; think of how effortlessly you can tear duct tape at a 90-degree angle. The key is to learn how to exert force on the tape to make it rip open. If your hands are in front of your body while you’re being taped, lean forward and press your forearms together; you’ll appear more compliant, and it’ll be easier to escape later. When your captors aren’t around, raise your arms above your head, like a church steeple. Then quickly pull your arms down and out to the sides past your hips, like you’re elbowing someone behind you. Alternately, you can also rub the tape on a sharp edge, like the corner of a door or furniture. If large amounts of tape are used, it’s applied in a figure-eight pattern, or your hands are taped behind your back, you may need to cut it with the cord saw method described below.

The tighter the tape and your wrists, the easier it’ll be to escape. While practicing these techniques repeatedly, wearing long sleeves will save your skin from getting thrashed. Raise your arms above your head, like a church steeple. Quickly pull your arms down and out to the sides past your hips, like you’re elbowing someone behind you.

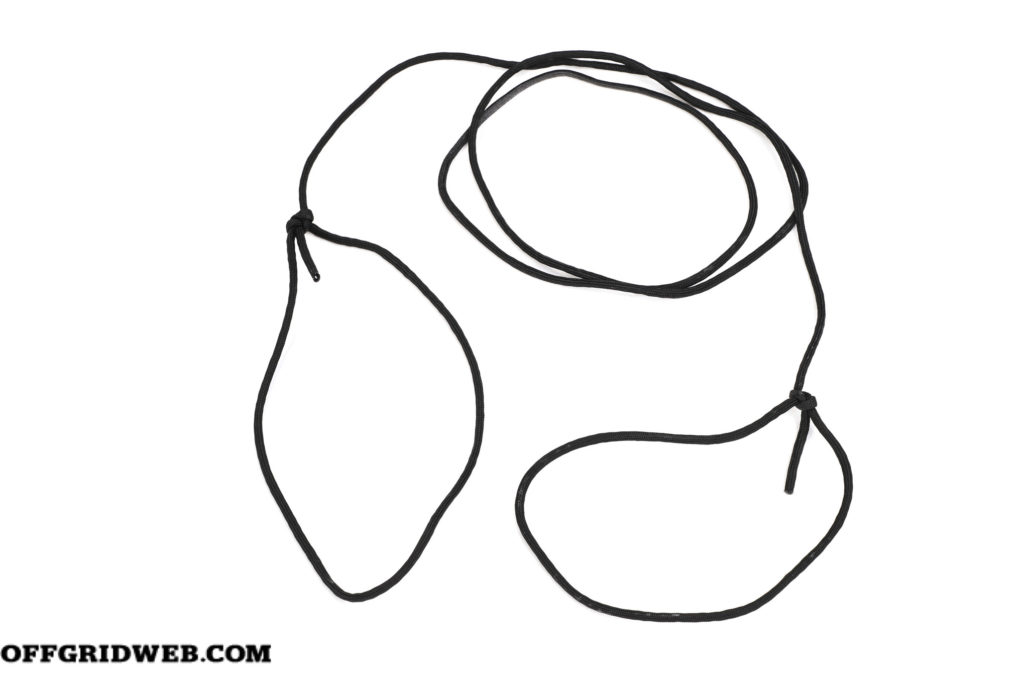

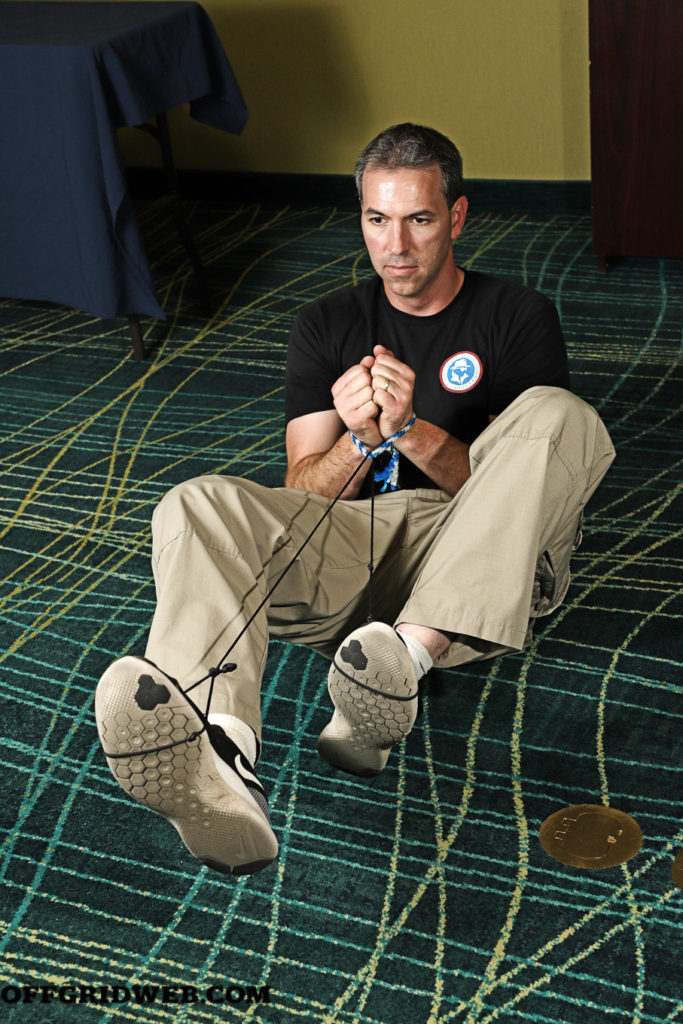

Zip ties: These are also frequently used and are harder to defeat than duct tape. For positioning and breaking free, follow the same steps as for duct tape; however, be sure to rotate the zip tie so that its lock is centered between your hands. You’ll need to exert a lot more force, get the angle just right, and it’ll hurt, so not everyone will be successful with this technique. There’s an alternative method, if you’ve stashed paracord, Kevlar thread, or other strong cordage somewhere accessible. Thread the cord through the zip tie, then tie loops on each end for your feet. Lean on your back and act like you’re bicycling. This will saw the cord clean through the zip tie. A similar kicking technique can be used if your hands are behind your back, but it requires more flexibility and patience.

You can use paracord or other strong cordage with two loops for your feet to saw through restraints.

Thread the cord through the bottom of the restraints. Secure the loops on your feet and move in a bicycling motion to saw through the restraints.

Rope: If you’re being tied up with rope, do the opposite as with tape or zip ties — pull your elbows against your body to keep them far apart, press your palms or fists flat together, and push your wrists apart. If you can do this, you’ll buy yourself more room to work with the rope. To get out, push your arms forward and straight, press your hands together, make knife hands, and shimmy your hands back and forth. After suffering through rope burn and scraped skin, you may eventually be able to pull your hands free. Alternatively, you can use paracord to saw through the rope, as with zip ties.

Above: While being tied up with rope, pull your elbows against your body, press your hands flat, and push your wrists apart. This will give you more room. Then, push your arms forward and straight, make knife hands together, and shimmy your hands back and forth to work them out of the rope.

Handcuffs: These are less common among criminals, but it’s good to know how to deal with handcuffs. It requires prior preparation — you can make your own pick or shim. Picking is harder; straighten a bobby pin and bend a quarter inch at a 45-degree angle at the end. Insert the leg into the keyhole with the bend pointing toward the center line of the handcuff and the scoop pointing up. Pull down and to the side to disengage the ratchet. Alternately, make a shim out of a hair barrette. Remove the middle part of the barrette, then bend and break off the fat end, leaving a V shape. Smooth out the cut edges and open the hinge, making it into a long shim. Insert the shim into the handcuffs where the ratchet’s teeth go into the cuff. Push the cuff further closed a bit while you push the shim in as well; be gentle so you don’t over-tighten the cuff on your wrist. This will allow the shim to block the teeth on the cuffs, and you can open them. Note that shimming is only possible if the cuffs aren’t double-locked, which prevents the cuff from closing over the shim.

Above: Insert the shim into the handcuffs where the ratchet’s teeth go into the cuff. Handcuffs have teeth on a pawl that secures the ratchet as it closes over your wrist. Use a thin shim to prevent the pawl’s teeth from engaging the ratchet.

The skill of getting others to do what you want is as old as the hills; social engineering is a fancy way of describing that psychological manipulation. Even if this evokes a negative connotation for you, it’s a crucial life skill. Whether being a parent or child, a boss or worker, or simply getting things done in the world, you influence the behavior of other people all the time. You’re also influenced by others. Therefore, developing a keener understanding of cognitive biases and how emotions affect decision-making can help you persuade others when needed. It can also help you recognize and mitigate when others are trying to take advantage of you.

Gaining a sense of whether people are fibbing or telling the truth is an immensely valuable skill, which Jason Hanson calls being a human lie detector. Most people aren’t very good at lying, so there are a number of indicators that you can watch for; you need to have a baseline, to give you an understanding of their basic, normal mannerisms to compare against. If you notice several indicators, that’s a clue to be wary. Here are several examples:

First 3 to 5 seconds: Someone who’s formulating a lie will often pause, stammer, get nervous, or stumble over their words after you ask the question.

Indirect answer: A guilty party may not answer your question directly, instead referring to wonderful things they’ve done to imply they’re an honest person.

Pointy feet: Our feet tend to point in the direction we want to go. If the person you’re talking to has their feet turned away from you, they may be lying, have something to hide, or at least want to get away from you.

Over-staring: Someone who’s lying may stare too hard at you, looking intently and unnaturally at you, hoping to convince you to believe them.

Overreaction: If you confront someone who’s lying, they can overreact to an extreme degree. This is often seen with infidelity; when a cheating spouse is accused of having an affair, they can become outlandishly enraged and flip out at the perceived lack of trust.

Head shake: Head movement that’s mismatched with what’s being said is a well-known tell, such as Lance Armstrong famously saying “yes” while shaking his head “no” during video-taped testimony on his drug use. Additionally, head movement usually comes before the words, so someone who says “yes” before their head starts nodding may be lying.

We spend a lot of time in our vehicles. A study in 2019 estimated that Americans spend an average of almost 8.5 hours per week driving. With all the potentially dangerous situations that you might encounter while driving, honing your survival driving skills is important. During Spy Week, we learned and practiced several key techniques:

Above: In one exercise, Hanson would throw a cone in your way at the last minute, forcing you to quickly change directions.

Secure your car: This is an obvious one, but always make sure to lock your doors and keep your windows up for maximum security.

Leave enough space: Ensure you can always see the tires of the vehicle in front of you, so you have enough space to get around them if necessary.

Evasive maneuvers: Learning effective car control will help you be able to flee from threats. We learned about managing weight transfer and braking in a straight line before adding steering input — any grip you’re using to stop is grip that can’t be used to turn. We did exercises to crystallize these principles, with cones set up in a slalom course as well as a roadblock drill, both forward and in reverse.

Downed driver: If the driver in your vehicle has been incapacitated, you can take over from the passenger seat. Firmly push their right leg out of the way and step over the center console, but be careful about hitting the gear shift. Shove your left leg into the driver’s footwell to work the gas and brake pedals. With your left hand, grab a handle or the back of the seat to stabilize yourself, and steer with your right hand.

Above: To take over for a downed driver, firmly push aside their right leg. Shove your left leg into the driver’s footwell to work the pedals. Stabilize yourself with your left hand and steer with your right.

J-turn: In that rare situation when you’re blocked and need to quickly escape backward, you can execute a reverse 180. Place your left hand at 9 o’clock on the steering wheel. Put the car in reverse and accelerate backward to at least 20 mph. When you want to do the J-turn, snap the wheel with your left hand around to the 3 o’clock position while taking your foot off the gas. The car’s nose will quickly spin around. Shift into drive and rock on.

Ramming a car: In the even more unlikely chance that you need to break through a blockade, you can ram a car. Aim for the rear of the vehicle near the gas tank, which is lighter than the front. Approach at roughly 20 mph, don’t lift off the gas and don’t hit the brakes as you make contact and push your way through. This technique shouldn’t be undertaken lightly, as modern unibody cars can sustain quite a bit of damage and your airbags may deploy.

Above: To break through a blockade, aim for the rear of the vehicle near the gas tank, approach at about 20 mph, and push your way through.

In RECOIL OFFGRID, we’ve frequently covered topics related to fighting with and without a weapon, and employing knives and guns. Hanson stresses competency with hand-to-hand, knives, and firearms as important components of self-defense, and a couple days during Spy Week are devoted to them. His curriculum covers similar frameworks to other excellent courses that we’ve written about before, with solid and modern firearms principles, practical self-defense concepts, and knife work grounded in the Filipino martial art of Kali. So, with limited space in this article, we won’t go too deep into specific techniques here.

With both rifle and handgun, Hanson covers the fundamentals of marksmanship, including grip, stance, sight picture, trigger control, and follow-through. We ran drills on shooting from various positions, recoil management, transitions, multiple targets, movement, reloading, and more. We worked in and around vehicles, then shot one with various weapon systems and observed how little protection the body of the car provides.

Above: Car doors are easily perforated by gunfire.

We trained defenses against typical abduction techniques like wrist grabs, choke holds, and bear hugs, or if you’ve been taken to the ground and mounted. Then, we layered in knives. We looked at key knife targets, including arteries such as the brachial, carotid, and femoral, the heart, intestines, mandible, abdominal aorta, and perineal area. Angles of attack can be horizontal, vertical, thrusting, or diagonal in various directions. We did flow drills with partners to practice motions, attacks, and defenses, in particular; redirection. Unfortunately, if you ever need to defend yourself against a knife, the likelihood of getting cut is very high. We all took a swipe at a piece of pork with a small knife to see how much damage it can cause.

As always, avoiding confrontations and breaking contact as soon as possible are far preferable to getting drawn into a fight of any kind. But you need to be prepared; carry a gun and a knife whenever possible, or a tactical pen otherwise. Building and maintaining proficiency in these areas requires training, practice, and dedication. Hanson urges that you make it a continuing priority.

None of the topics we covered at Spy Week are rocket science. But like many things in life, effective application of proper fundamentals is the cornerstone of excellence. The CIA understands this better than just about anyone, with hard-won, bloody wisdom gained from experience in the trenches, metropolises, and back alleys all around the world. Thus, it trains its operatives accordingly with best practices from a variety of disciplines.

Above: During Spy Week’s Trunk Challenge, you’re handcuffed or duct taped and stuffed in the trunk of a car. Disoriented and in the dark, you have to free yourself.

Hanson’s Spy Week course isn’t cheap, but his clientele tends to be affluent, and he provides integrated one-stop shop training for all these important topics across a weeklong experience. He also provides all necessary gear for those who need it. You can also select one of his shorter, more narrowly focused courses. Our Spy Week class was attended by several business owners and contractors, a longshoreman, a private investigator, a bail bondsman, a Master-class competitive shooter, and a former Blackhawk crew chief from the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment, among others. Many came as married couples, another as a father-son combination, which is great to get the whole family synced up.

Take a page from the CIA’s book — cultivate these skills and qualities, and unleash your inner spy.

Find Out More at: spyweek.com

STAY SAFE: Download a Free copy of the OFFGRID Outbreak Issue

STAY SAFE: Download a Free copy of the OFFGRID Outbreak Issue

No Comments