RECOIL OFFGRID Survival The Viral Truth

In This Article

The United States has seen its share of tragedy in the 21st century and since then, the nation that we call “home” has changed dramatically. Public health officials have been cautioning Americans since 2001 that a horrific pandemic has been lurking at our doorsteps to infect every world citizen. In fact, public health agencies around the world gave dire warnings about the horrors of H1N1, Ebola, SARS, and MERS, all of which were deadly in their own right, but failed to cause the level of death purported by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The fact of the matter is world citizens lucked out with those disease outbreaks. But that was then…

Once again, the landscape of our world has witnessed historical changes unseen since the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic, which was responsible for anywhere between 50- to 100-million deaths. Ironically, even though the Covid-19 pandemic is different than the Spanish Influenza, one does not have to dig deep to understand that many of the societal struggles we face with today’s pandemic are very similar to those witnessed during the 1918 outbreak. Modern society is larger, faster, and more prone to accepting conflicting information today than it ever has in the history of mankind. Since the inception of social and mainstream media, most world-residents remain in a constant state of confusion as to what constitutes fact over fiction.

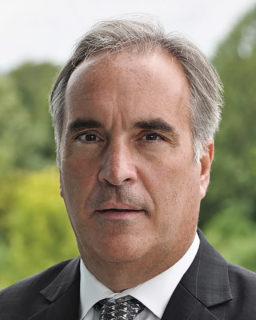

To help alleviate some of that confusion, RECOIL OFFGRID Magazine has brought together a few experts to examine the lines between fact and fiction surrounding the Covid-19 pandemic. Dr. Amesh Adalja is an expert in infectious diseases and emergency medicine from the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. He’s joined by Dr. Eric Dietz, director of the Purdue University Military Research Institute and Jeff Schlegelmilch, director of the National Center for Domestic Preparedness at Columbia University. Finally, Dr. Tim Frazier, faculty director of the Emergency Disaster Management program at Georgetown University, will combine his extensive field expertise to aid in the article’s search for answers with Dr. Robert Quigley, senior vice president and regional medical director of International SOS. All panelists will share their in-depth knowledge to help answer the question we are all asking: Is the truth about Covid-19 still out there?

“It’s always a good thing to re-evaluate where we’re going, and we should demand that of our elected officials and health professionals who are charged to keep us safe.”

— Eric Dietz

AHMESH ADALJA

AHMESH ADALJA

Dr. Adalja is a Senior Scholar at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security. His work is focused on emerging infectious disease, pandemic preparedness, and biosecurity. Dr. Adalja has served on U.S. government panels tasked with developing guidelines for the treatment of plague, botulism, and anthrax in mass casualty settings and for the system of care for infectious disease emergencies.

ERIC DIETZ

ERIC DIETZDr. Dietz’s research interests include optimization of emergency response, homeland security and defense, energy security, and engaging veterans in higher education. As a director of the Purdue Military Research Institute, Dr. Dietz organizes faculty to involve current and former military in Purdue research with focus on defense and security projects to increase Purdue’s involvement in national defense.

TIM FRAZIER

TIM FRAZIERDr. Tim G Frazier is a full professor and the faculty director of the Emergency and Disaster Management program at Georgetown University. Dr. Frazier’s research focuses on developing science that serves to impact decision-making in local communities through stakeholder engagement.

ROBERT QUIGLEY

ROBERT QUIGLEYRobert L. Quigley, M.D., D.Phil., Professor of Surgery, Senior Vice President and Global Medical Director, Corporate Health Solutions, International SOS Assistance & MedAire, Americas Region, is responsible for leading the delivery of high-quality medical assistance, healthcare management and medical transportation services. He’s the executive chairman of the International Corporate Health Leadership Council as well as the chairman of the Council for U.S. and Canadian Quality Healthcare Abroad.

RECOIL OFFGRID: What statistics are used to gauge the severity of a disease outbreak?

Amesh Adalja: There are a lot of statistics out there, and it depends on what your purpose is when looking at statistics and finding what is useful to you. When examining the spread of disease, the number of cases is one aspect to look at, but that has to be adjusted for how much testing is going on. There are places that are increasing and decreasing their levels of testing, so you have to look is the percent of positivity. In other words, how hard is it to find a new case, which is an important number to look at because it’s an indicator of what the community spread is. It’s important to keep in mind that patient deaths are a lagging indicator, so you’ll likely not see an immediate rise in deaths if you see an outbreak spiraling out of control. That’s also another marker to look at for the severity of the virus.

Eric Dietz: One thing to keep in mind is that all statistics are very different. The spread rate might be very high, but we may not care as much if the disease is not lethal. If the lethality is high, however, we’re going to have a significant concern. There are a variety of factors involved in determining statistics such as how fast it spreads, its lethality, and severity of the symptoms. Each one has its own quirks, especially as they relate to Covid-19 and new data emerges.

Tim Frazier: What’s critical at this point are looking at infection rates, the number of new cases from a day-to-day perspective to track the spread, and to track mitigation measures.

Robert Quigley: Metrics such as number of deaths, number of cases, rate of new cases all can certainly be valuable in gauging the severity of COVID-19 in any one jurisdiction. However, they are far from complete, and methodologies in interpretation can vary from region to region. The denominator (i.e. the total number of cases) can only be determined by testing. That said, the combination of limited testing resources and asymptomatic vectors (unknown to public health statisticians) makes calculation of the denominator next to impossible, so at any one time we only see a fraction of the actual cases, which would not permit accurate reporting on the rate of new cases.

The reality of the pandemic is that a lot is not fully known about the exact benefit of potential safety measures. Ventilation, air filtration, masks, and social distancing all have a positive effect in limiting the spread of the virus. There is a lot of modeling, retrospectively, to understand the value of each of these measures. When you’re dealing with an infectious disease, you are dealing with a variety of factors such as transmission through shedding, through vapor droplets, and so on. It’s important to understand that wearing a mask is not to protect me from you, but it’s worn to protect you from me. The precise value of masks is not known, but they are an important tool in the toolbox to lessoning the spread of the virus.

What source numbers are used to compile patient data for Covid-19?

AA: Most data is being collected by local and state health departments, and they are providing essential situational awareness. The data is vital to hospitals when they decide upon whether various elective procedures can fit within their capabilities, all of which are stressed due to the pandemic. It’s also important to note that all data is not iron-clad. There will be fluctuations in the data that are contingent upon several factors, which is normal in this field. Collected data, however, still gives an over-all view of the viral activity within our communities.

ED: I also look at peer-reviewed journals where other scientists have examined many issues surrounding Covid-19, develop their own analytical data, and then share that data with the community.

RQ: The public health authorities, such as the CDC and Johns Hopkins, responsible for collecting/interpreting/sharing data have COVID-19 dashboards, situation reports, and daily data tables accessible on their websites. Their data sources include all of these as well as regional ICU admissions, recovered patient numbers, local/national lab results, as well as data developed from morgues and funeral homes.

TF: The number of new cases is reported by medical facilities to local health departments, so health departments have the cases needed to compile a list of statistics to report to State Health Departments. For example, if someone has it and they don’t go to the hospital, then it won’t get reported. In all likelihood, the cases of Covid-19 in the Nation are under-reported and surpass the data we actually have on record.

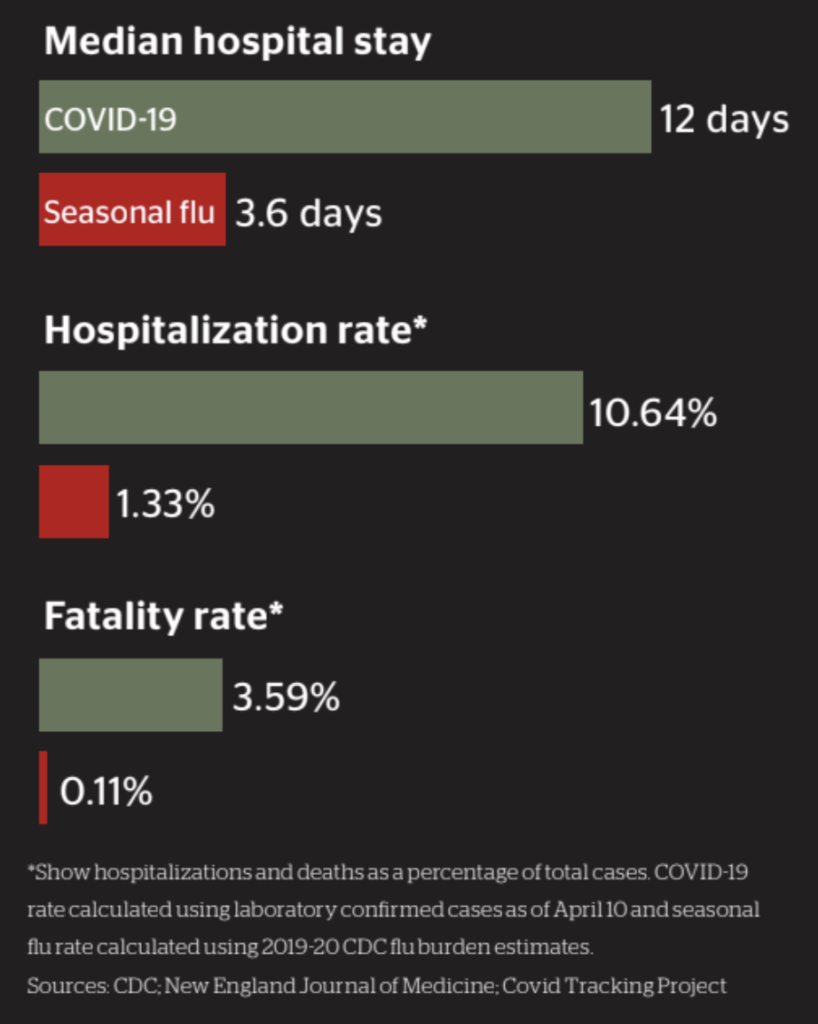

The key two differences between COVID-19 and influenza are the transmissibility of COVID-19, as well as its fatality rate. We’ve seen other Coronaviruses such as MERS, which has a high fatality rate but is not very transmissible. Flu is highly transmissible but does not have the fatality rate that COVID-19 exhibits. The ability to spread easily and kill a higher proportion of people are what separates COVID-19 from other common viruses and make it a deadly pandemic today.

What, if any, mechanisms are in place to prevent false or inaccurate reporting?

AA: Health departments should try to remove duplicates if someone had more than one test, or different types of tests, that came back positive. That should only be counted as one positive case and not two. We see this in cases where someone will be tested for the virus to be discharged from a nursing home, and then tested again to see if they are cleared to move back into the same institution. When you look at deaths, there is an adjudication process in which health departments will see if a death was caused by Covid-19 or was it incidental to Covid.

ED: The duplication of reporting is something that many of us are frustrated with right now. There does not seem to be a quality control part of the program that really understands how many in the nation are really sick. All that we know now is the number of positive cases that are in a geographic location, but we also know that same positive individual may have been tested several times. Each positive person might be contributing an amount of positive tests back into the pool of data which allows some to claim that there is much more disease than there might be. We need to get a handle on quality control before we progress with this pandemic or prepare for the next one that might put us in a more difficult position.

“There are a lot of slanted pieces of information out there, as well as “arm-chair epidemiologists” who are attempting to re-define data and reconceive notions.”

— Amesh Adalja

RQ: Laboratories, by no fault of their own, can only report results as they are generated. The false positive/negative rates are simply a reflection of the efficacy of their tools. Unfortunately, the testing tools are not standardized, so different labs will be expected to have different accuracy rates in reporting. Whether testing for antigen (SARS-Cov-2) or antibody (IgG), no test is 100% accurate. Tests need to be performed on a large number of samples and validated multiple times in order to get an estimate on specificity/sensitivity. Finally, because this virus is novel, more research is still required in order to define quantitative thresholds for accuracy in the short and long term.

TF: I would say that there is a level of inaccuracy on reporting and under-reporting. There is probably a range of error that we don’t know very well. There are deaths that are getting reported as Covid-related that aren’t Covid-related. I think that the challenge is to understand what the error margin is and being okay with a certain percentage of error margin in the reporting and under-reporting of cases.

There are echoes to the politics of 1918, such as the opposition to wearing masks. There are also stories of communities coming together to figure out how to beat both diseases. There is also a longer shelf life to the political science than there is to the health science when exploring the social aspects of both pandemics. However, during the 1918 outbreak, there were not nearly as many advances in the health industry, and it was based on old-school epidemiology which hasn’t changed much today.

It’s also worth mentioning that even in absence of game-changing therapeutics, there’ve been improvements in how we treat people with Covid-19. The transfer of information is tremendously quicker than it was in 1918, which makes data and peer-review dispersal among healthcare organizations that much quicker. The research and response measures are moving faster than they feel. Pandemics, much like the 1918 Spanish Flu, just take a long time to get through.

How does timing come into play when we study data? How soon is too soon for data to be considered valid?

AA: You must remember that when you see a daily case count from a county health department, that those are not the cases that occurred the day before. There are often going to be lag times in reporting, so you’re never seeing a snapshot of cases that occurred during that particular day. Usually those numbers reflect positive-test cases from a week prior. It’s not a highly precise number, and that’s not an attempt to fault anyone. It only reflects the nature of the data reporting process, especially during a novel virus outbreak. The data is collected not for data’s sake, but to gain a sense of the issue so we can institute the public health actions needed on an individual and community-wide basis.

ED: The issue we have surrounds the type of data we want and how do we want it characterized? We must figure out how we’re going to analyze data before we ever collect it. This is one of those cases in which the data methodology needs to be carefully thought through. It’s an ongoing problem that plagues every disaster that we’re faced in America, and we’re going to have to ask ourselves how we’ll distribute an eventual vaccine based on the data we’re receiving during this pandemic.

TF: Within a matter of days, the data finds where it needs to go and probably anything more than a week old is out-of-date at this point.

RQ: Timing is critical when interpreting scientific data. For example, testing infected individuals too early can produce false negative results. Reviewing epidemiologic and demographic data when the denominator is too low could produce an exaggerated “R naught” (viral reproduction rate) as well as an exaggerated mortality rate. The question isn’t “how soon is too soon,” but rather “when do we have a statistically significant sample size from which to draw a conclusion?”

More than half of Americans carry chronic conditions and we have an aging population that carry more than one chronic condition. Anytime those are present, you are at a higher risk for exacerbating those conditions with illness. Even if that was a smaller part of the population, we’re still seeing huge numbers of deaths that don’t need to happen. As a civil society, we have a responsibility to protect each other. If you go out to overly crowded locations, you’re potentially bringing the virus home to someone and introducing it to another environment. One of the reasons that the playbook from the SARS outbreak in 2003 isn’t working is because the virus is spreading before people are symptomatic or don’t show symptoms at all. We may not be sick but are shedding the virus, and the elderly person behind us in the grocery store could die from it. There are a lot of people out there who say that this pandemic is not so bad, but all you have to do is look to the refrigerated trucks to store dead bodies in when the morgues in New York City were overwhelmed with bodies.

What are some ways that the average person can distinguish accurate facts from misleading facts that are slanted one way or another?

AA: For the average person, it’s very hard to determine what is valid and not valid. People should stick to websites that have been validated to receive their information, such as the CDC or state health department, with the caveat knowing that those numbers will fluctuate depending on the type of data collected and when that data was collected. Regardless, it will be very hard for the general public or someone who does not have a background in this field to distinguish the accuracy of the information out there. There are a lot of slanted pieces of information out there, as well as “armchair epidemiologists” who are attempting to redefine data and reconceive notions.

ED: It’s a frustration that all of us have right now with the mainstream media who practice an overly politicized system of reporting in our nation. I think that any institution that’s relaying contradictory information to the public has a duty to let the public know, with a little more clarity, as to why we’re taking some of these measures during the pandemic. Since there are numerous information sources available to the public, it’s important for us to find those sources that are cited and verified so we can gather information that is trustworthy and consistent with our values. We also need to reevaluate our actions and that we’re doing things that are effective, and not because someone is trying to socially or politically pressure us into doing something that makes doesn’t make sense.

RQ: Scientific reporting and politics are incongruent. The reporting of clinical or scientific data should always be done in an apolitical forum to avoid any misrepresentation of the facts. Unfortunately, many search engines used today are not apolitical. The closest source of untarnished data may be the actual peer-reviewed literature.

TF: I would hate to say that this has been over-sensationalized, but I may steer clear from publications such as blogs and newspapers. The most accurate sources of information will be available from the CDC, which is very good at what they do, and they are going to give you the most reliable information that you will need. Local health departments will also give information that is specific to that particular county, so someone looking to track the spread of Covid-19 would do better to follow the information from those sources.

Right now, we have a generation with key developmental milestones. Even if there is a vaccine, it’s not going to be effective enough to quickly undo the precautions set in place right now. There is also some long-term trauma that Americans have faced, be that a loss of a job, isolation, emotional and physical grief that exacerbates mental health issues, and delays in developmental milestones for children that could follow them their entire lives. These are all things that we don’t fully understand the long-term impacts yet.

Even with the Covid-19 stimulus bills, we are racking up an enormous amount of National debt while climate change still occurs, and natural disasters are increasing. Wherever the pandemic goes, the trajectory of natural disasters is only going to increase, and the resources that we need to mitigate disaster in vulnerable areas is being depleted right now. All of these put a lot of pressure on the future.

There is also a silver lining here if we look for it. We’re better at remote work than we ever have been before because everyone is getting better at technology. We have to be. In that way, this pandemic is really accelerating aspects of our civil society and economy. This trajectory has been established, and I don’t think that we are going to go back to the way it was before Innovation is always hard to predict but is prevalent during times of necessity when solutions are needed. Covid-19 is no exception to that.

Are patients who have died for reasons other than Covid-19 still tested for Covid-19, and if so, why?

AA: There is some misinformation of what happens when you fill out a death certificate. A Covid-19 death, for example, can be complicated by things like diabetes or hypertension, so all three will appear as a cause of death on the death certificate. Medical practitioners are just trying to give as much a comprehensive picture of the cause of death as possible, so we list all co-morbidities on death certificates to gain a realistic idea of how someone died. It’s a frustrating conversation that we’ve been having with others because it detracts from the real work that should be done. Valuable time and resources are being spent to focus on conspiracy theories that are completely false. I would argue that when someone makes these types of claims, they should examine the excess deaths in cities that have been hit hard and compare it to one year ago. After comparing that data, it becomes very hard to argue that Covid-19 is not a deadly disease.

ED: We’ve gotten a lot better in understanding how this disease works, but there are still instances in which Covid-19 is attributed to deaths that shouldn’t be. I would understand testing for deaths in a nursing home to better understand how Covid-19 entered the facility. Nursing homes are a very dangerous place to allow the virus to enter, which are also prone to influenza-related deaths. As we go into flu season, I can see a greater need for testing to distinguish Covid-related deaths from flu-related deaths, but there still needs to be some checks and balances to ensure that deaths un-related to Covid-19 are not attributed to the pandemic.

RQ: This could happen for multiple reasons. There are times when pre-morbid testing results revealed a false negative. Also, antibody data can provide more demographic data for the public health authorities used for activities such as contact tracing. There have also been instances when the death occurred at home, and the deceased have not been tested in any healthcare facility

TF: There could be some who are tested for fear of that patient’s relation to a population mass for the sake of contract tracing, but I feel that those cases may be on a more limited scale than those who were suspected to die from Covid-19.

The short answer is that we don’t know. The long answer is mixed with a little bit of speculation and a little bit of information. There have been tests on tens of thousands of those who have recovered from Covid-19 who are not showing any signs of resurgence, so that is very reassuring. The bigger question is how long will the immunity to Covid-19 last? Covid may be like influenza, which replicates in a very messy way, so it tends to mutate, or “drift.” Therefore, we need a seasonal flu vaccine every year. So the question will be if people infected with Covid-19 will have a wavering immunity in which the virus weakens and they can get sick with it again, or will it shift so that they can get infected with a natural mutation of the virus? No one yet knows the answer to that, but the medical assumption is that even with a vaccine, people will still need a yearly booster shot.

Where do we go from here?

AA: We have normally lived in a world where we didn’t have to think about infectious diseases, but now we’re going to have to start looking at life a bit differently when we walk out of the door. Every activity that we do is going to have some sense of risk, whether that be contracting the virus or spreading it to someone else. It doesn’t mean that we stay at home forever, but rather be mindful of our activities and taking simple measures of protection. It will take some adjustment, but we have the tools to live safely and now it’s time to exercise those tools.

RQ: Getting beyond the pandemic will require herd immunity either from an effective vaccine or infection of the global community resulting in an R-naught value less than 1. In the meantime, mitigation efforts will require compliance by all, which include social distancing, mask wearing, and universal precautions such as proper handwashing.

TF: What we see in our field today is that everyone is their own emergency manager. They take pieces of information from a variety of sources, and they assemble that information to make their own decision. This makes it challenging because we are not always getting the most accurate information, and we don’t weigh the information from those sources. There is a lack of understanding of how this disease works, and simple things like washing your hands, not touching your face, staying away from crowds, and wearing a mask would really mitigate the spread of this disease.

ED: This is great time to remind everyone to thoroughly wash their hands and stay home if they’re sick. There is so much that we can do on a common daily basis that would turn out better if we just simply did those things. Our Nation is designed by intention to be safe and free, but our freedom is part of our safety. We’re free to get away from things that we don’t feel safe with, and we don’t want the government to tell us to certain things. At the same time, we must be able to make some of these decisions for ourselves. It’s always a good thing to reevaluate where we’re going, and we should demand that of our elected officials and health professionals who are charged to keep us safe. Our safety should not be something that we sacrifice for our freedom. Those two must go hand-in-hand.

Jeff Schlegelmilch is a research scholar and the director of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University’s Earth Institute. His areas of expertise include public health preparedness, community resilience and the integration of private and public sector capabilities, and has recently published his book, Rethinking Readiness: A Brief Guide to Twenty-First-Century Megadisasters.

There is a Chinese proverb which states that “nothing is to be feared, only understood.” Modern medicine has advanced rapidly in the past one hundred years and is on the brink of medical breakthroughs that teeter on the edge of miraculous. Diseases, however, continue to strike fear into our hearts as we struggle to understand them. History has proven that societal and political landscapes have been altered by disease outbreaks, and we are reminded of our humanity by the historical scars they leave behind, granting us lessons that we struggle to remember.

“What we see in our field today is that everyone is their own emergency manager. They take pieces of information from a variety of sources, and they assemble that information to make their own decision.”

— Tim Frazier

The Covid-19 pandemic will go down in history not only for its impact on our health and well-being, but maybe more so for its revelation of the deficiencies in our societal arenas. No individual’s health should be fodder for political gain, nor mixed within the spectrum of confusion sowed by those seeking gain from disaster. The health of the Nation does not play well as a social chess piece, but should be held in the highest of esteem as we navigate through the both the physical and civil treacheries of the Covid-19 pandemic. The fog of war created by the pandemic underscores that fear of the disease should be balanced by a healthy understanding of the threads that hold our great nation together…our humanity.

Mark Linderman is a Certified Emergency Manager (CEM) and 20-year veteran of public health. He instructs disaster preparedness courses for seven universities, including Indiana University’s Fairbanks School of Public Health and teaches Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication courses for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mark is considered a subject matter expert in the field of disaster-based communication and is a widely received public speaker and advocate for disaster preparedness. He channels his passion through his own blogsite, Disaster Initiatives, where he regularly interviews world-renowned survivalists, authors, academics, and government officials.

STAY SAFE: Download a Free copy of the OFFGRID Outbreak Issue

STAY SAFE: Download a Free copy of the OFFGRID Outbreak Issue

No Comments