RECOIL OFFGRID Survival What If Your Family is the Victim of a Mountain Lion Attack?

In This Article

Illustrations by Robert Bruner

It’s a beautiful summer day, so you decide to go for a family hike/picnic in the nearby Cleveland National Forest with your spouse and two children (ages 10 and 7). You’ve hiked this area before and are relatively familiar with the various hiking paths that lead to scenic areas with natural hot springs, where you plan to stop for a picnic. The hike out and back with a stop for lunch should take about four hours total. You pack plenty of water, an insulated bag full of food, and comfortable clothing before heading out to a trailhead off Ortega Highway between San Juan Capistrano and Lake Elsinore, California. The last thing on your mind is being the victim of a mountain lion attack.

This area of the Cleveland National Forest is vast, and although you have a cell phone, reception is spotty in many areas, U.S. Forest Service and park ranger presence is limited, and you’re at least a 45-minute drive from any hospitals. You’re also aware there have been recent mountain lion attacks in the area, so you’re conscious of the location of nearby Forest Service fire stations in case something should happen and you end up in desperate need of medical attention.

Situation type

Mountain lion attack

Your Crew

You and your family

Location

Southern California/Cleveland National Forest

Season

Summer

Weather

Warm; high 97 degrees F, low 63 degrees F

The Setup: It’s early afternoon when you arrive at your destination. You decide to hike through a known, but uncommonly traveled trail that goes to the San Juan Hot Springs, a relatively secluded area. The hike will take you inland by a few miles, but you feel the beauty of the destination is worth the extra effort. After walking for about half an hour, you stop to take a breather and rest your feet.

The Complication: As you gaze around and estimate how much farther you have to travel, suddenly you hear a blood-curdling shriek from your youngest child who had been standing a short distance away. As you turn in that direction, you see a large mountain lion walking off into the brush carrying your child by the neck in its jaws. It climbs an oak tree about 150 yards from where you are and settles on a branch about 7 feet off the ground with your child gasping for air.

In a panic, you reach for your phone to find that it says, “No service.” Calling for help from this location isn’t an option. What do you do? Should one person run for help while the other attempts to free your child? Will attempting to confront the animal and free your child risk greater trauma or possibly death, making a bad situation worse? If you had a weapon, would it be too risky to use it? What steps can you take to protect your child and escape?

Having spent the first three of my 28-year California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) game warden career patrolling this region within the Cleveland National Forest, I’m intimately familiar with mountain lion presence and encounters in western Riverside County and throughout the rest of California. The CDFW reports there are between 4,000 and 6,000 mountain lions residing in California and have verified 17 mountain lion attacks on humans between 1986 and February 2020.

An additional four fatal mountain lion attacks occurred around the turn of the previous century. Of the modern era’s 17 attacks, 3 were fatal, and 8 victims were children under the age of 11. While these statistics are alarming, the relatively low number of mountain lio attacks over this 34-year period tells us the likelihood of getting attacked by a mountain lion is extremely low, especially given the millions of outdoor recreationalists adventuring throughout mountain lion habitat on a daily basis throughout the Golden State.

Preparation

Adequate first-aid supplies (in both your pack and vehicle) for any outdoor contingency are critical, especially when going into an area known for lion attacks. Trauma gear for gunshots, broken bones, and deep puncture wounds that generate heavy arterial bleeding are a must. The following essential trauma items are always in my pack and vehicle for redundancy to cover any trauma medicine contingency: hemostatic gauze (QuikClot/Celox) pack, at least one Israeli bandage, two C.A.T. tourniquets, 4×4 gauze bandages, and a roll of first-aid adhesive tape. Having these supplies on hand is critical, as is the knowledge to deploy them efficiently and correctly should the need arise. Well before this hike, I’ve trained the entire family how to use these tools properly and refreshed them again on these skills since we’re going into a known mountain lion habitat.

Other essential items in our vehicle are plenty of water; electrolytes and two water purification devices; an emergency space blanket; food (at least two days’ worth in the event of an unplanned overnight stay in the backcountry); a fire-starting tool; a sharp multipurpose knife and sharpener; a compact semi-auto pistol with integrated white light and laser combination (chambered in a caliber adequate to stop a wild animal attack with controlled expansion hollow point bullets); an extra pistol magazine; a handheld GPS device with onX Hunt topographical map program installed; a flashlight/headlamp; extra lithium batteries for all the devices carried; sunscreen; a wide brim “boonie” style hat; light jackets; and other layering clothing. I also carry an Iridium satellite phone in my pack for remote backcountry areas without cell coverage.

Food storage in both our vehicle and especially in our backpacks while in the field is of concern in this region not only for mountain lions, but other wild animal species too. Breaking food items down into quart or gallon Ziploc bags significantly dampens, if not eliminates, fresh food smells on the trail. Remember most wild animals’ sense of smell is exponentially better than humans, so eliminating this preventable animal attractant where possible is essential.

Because of recent lion attacks in the region, I’ve analyzed the topographical maps for the area we’re exploring and chose a route on a marked, well-defined, and open trail with good 360-degree visibility surrounding it. While mountain lions can attack anywhere, they’re more comfortable and likely to do so in densely wooded areas where they can stalk close to their prey undetected. We’ll stick to more wide-open trails on this hike and not make it easy for them to attack. In the event of an attack, we’ve also identified at least two (primary and secondary) evacuation routes back to our vehicle utilizing open, high-visibility trails where possible.

Since I prefer to carry at least my pistol in austere backcountry areas, our family needs to be familiar with the firearm possession laws in the Cleveland National Forest. Firearms are generally allowed to be possessed on National Forest lands throughout the U.S. only during legal hunting seasons. The exception to this restriction is that those with a concealed carry weapon (CCW) permit may carry their firearm on U.S. Forest Service lands year-round. This hike is happening during a peak summer month when hunting seasons are closed, but fortunately I’m able to carry my pistol under the provisions of my CCW permit. Remember that rules may vary throughout the nation, so be sure to check firearms carry regulations in the area you intend on exploring.

Given confirmed mountain lion presence and reported attacks in our chosen hiking area, we must review measures to prevent an attack from happening in the first place as well as the most effective response if an attack occurs. Prevention starts with the following guidelines: Hike in numbers, as attacks are less likely in a group. Don’t let small children wander off the trail unattended. Keep your kids in the middle or front of your group to prevent a cougar ambush from the rear. Avoid areas with freshly killed animals, as cougars often stash their kills to eat later and will defend their meal. Leave the area immediately if you come across cougar kittens — lions will defend their young. Small dogs can attract or invite cougar attacks, so unless you have a large, situationally aware K9 with extensive backcountry experience, it’s best to leave them at home.

If encountering a mountain lion, don’t run away. Running may trigger an attack. Never turn your back to a lion; maintain constant eye contact with the cougar while making loud noises, yelling, and waving your arms as you deliberately gain distance from the animal.

If the encounter turns into an attack, don’t play dead. Fight back using your hands, legs, and anything else that can be used as a weapon. If you carry a firearm and have the proper ammunition, training, experience, and mindset to effectively neutralize an attacking lion, a gun can be a very effective tool to stop an attack. Before using a firearm, however, you must make sure the situation allows for a safe shot (position of animal, safe backstop, crossfire with other people, etc.) before pressing the trigger. Because California mountain lions are protected mammals on both public and private property and can only be dispatched for public safety reasons (verified attack or potential attack) and/or in depredation cases (livestock, pet loss, etc.), be prepared for the investigation that’ll ensue if you have to dispatch an attacking lion with your firearm.

While using pepper spray may stop an attack some of the time, I’ve seen and heard of numerous cases where it didn’t. Given this, be ready to use any available defensive weapons like rocks, sticks, knives, and other instruments. Several cougar attacks have been thwarted by striking the animal with improvised weapons including bicycle tire pumps, soda cans, water bottles, and even an entire mountain bike in one notable case. Bottom line, don’t give up. Exhaust every defensive tool within reach to survive the attack.

On Site

Identifying mountain lion and other animal tracks and scat along the trail is also critical. These indicators verify if a threat exists and tell us not only how recently, but also how frequently that threat is in our region.

Realizing medical assistance will be a long time in coming, trauma gear is readily accessible in my pack, and I have emergency response numbers (USFS, Cal-Fire, and sheriff’s 911 dispatch) preprogrammed in our Iridium satellite phone. For added family protection, I’m first on the trail with my handgun holstered and quickly accessible. Behind me is our 7-year-old daughter, followed by our 10-year-old son with my spouse at the back of the line, also armed with a handgun.

The safest hiking method for preventing a mountain lion attack, this formation also gives us the largest and most deterring presence possible. If we unfortunately come across a lion or other predator along the trail, my family will stay behind me while I cover the animal’s approach with my pistol. We’ll stay close together, moving around and away from the threat as a unit while waving our arms and yelling at the lion to make the largest and most intimidating presence possible as we gain distance away from the stalking predator.

Crisis

When our youngest child is attacked, dragged off, and pinned between a lion’s jaws in the tree above us, we respond quickly and deliberately. With severe puncture wounds to our child’s neck, the lion stationary in a tree above us, no cell coverage, and help at least an hour away, it’s up to us to save our family.

Keeping our team together and behind me in a safe cover position, my spouse activates the satellite phone to call for help while watching our back for other predators in the area. I move into position for a broadside shot, ensuring our child isn’t in the line of fire before engaging the lion with enough shots to the cat’s vital zone to stop the threat and force the release of our child. Cougars are thin-skinned animals and having dispatched several public safety/depredation mountain lions throughout my career with my duty pistol, I see these shots neutralize the cat effectively as it drops from the tree.

With the lion and our child on the ground, I ensure the cat is neutralized and begin assessing wounds for severity before starting treatment immediately on my child. She’s conscious, yelling in pain, and bleeding from the back of the neck, but fortunately the puncture marks indicate no damage to the spinal cord or carotid artery. I stop the bleeding using a QuikClot gauze pack, 4×4 gauze pads, and a compression wrap, while maintaining spinal precautions. Given the chance of unseen spinal damage or concussion, hiking out to safety isn’t an option. We’ll need a helicopter evacuation. As I maintain trauma care, airway, shock, and concussion protocol monitoring with our 11-year-old’s assistance, my spouse is on the sat phone with a 911 dispatch center giving our exact location through GPS coordinates. She conveys identifiable landmarks around us for an inbound helicopter crew to easily spot. She requests a helicopter that has a medic, hoist, and Stokes litter system aboard to evacuate a non-ambulatory victim quickly — capabilities very few air ships have for these types of emergencies. Following the call, my spouse photographs the scene with her cell phone camera. I monitor our child while maintaining scene security, keeping our family far enough away from the lion carcass and surrounding area to avoid inner perimeter contamination for the pending wildlife attack investigation.

With two small children, the possibility of an animal attack, especially a mountain lion attack, is always on our minds whenever we head out for an adventure. We often hike in mountain lion country, so while we want to have fun on our hike, we’re also on high alert. With more and more people getting outdoors and encroaching on nature’s territory, predators are taking more chances.

Preparation

Whenever we head out for a hike, we pack the essentials: snacks, water, a small survival kit, a first-aid kit, sunscreen, and bug spray. Both my husband and I each conceal-carry our respective firearms; we also each have a folding knife. In instances where we aren’t allowed to carry firearms (like many places in California), we carry bear spray and an air horn, in addition to our knives. Bear spray has been known to deter mountain lions and bears. An air horn has also been known to spook predators. In addition, our Jeep is stocked with a large first-aid kit, food, water, and a ham radio.

Before heading out, I always do some research on the area we’re about to explore, which would include researching the local animals. Knowing what’s out there will allow me to know what I’m looking for as far as tracks, scat, etc. If I’m unfamiliar with what tracks or scat an animal makes, I’ll search for that at the same time. I’ll even download pictures onto my phone so I can compare while out in the wild.

When doing research, I also look up self-defense laws, specifically when it comes to animal and mountain lion attacks. In California, the law allows you to defend yourself against a wild animal attack if there’s danger of an immediate attack.

On Site

Whether we’re in mountain lion country or not, we always tell our children to stay close to us and in turn, we stay close to them. In general, we try to keep our kids in between us, so we always have eyes on them, as well as the surrounding area. Plus, big cats like to come from behind, so we wouldn’t want our children to bring up the rear. Of course, because they’re children, oftentimes we have to continually remind them and/or guide them back between us as we walk.

If we were to spot a mountain lion early, we’d be as loud as possible — scream, stomp feet, jump up and down, wave arms, and so on. We’d stand our ground and show our dominance. Whatever you do, don’t run!

Crisis

Despite our best efforts, there may be times when we stop to rest or inspect a specific area, momentarily letting our guard down. If this were to happen and a mountain lion took the opportunity to attack one of my children, taking action immediately is critical. One parent would remain behind with the other child and attempt to call for help, while the other would move in to rescue the child who’s being dragged away by the mountain lion. One parent leaving wouldn’t seem prudent in this instance, as the other parent may need assistance with the animal or the wounded child.

Whether or not I knew my child was conscious and aware, I would yell to them to scratch, kick, punch, claw, do whatever they could to hit, hit, and hit some more. Of course, they’re afraid and hurt, so they might be unable to do anything at all. However, fighting back is generally key to breaking free from a mountain lion attack.

Reaching for my phone wouldn’t be my first priority — my priority is to get my child free and rush them to safety. My adrenaline would be pumping, I’d be scared, angry, and I’d put all that energy into stomping, screaming, being as loud as possible, throwing sticks, throwing my gear, throwing rocks, throwing anything I could get my hands on. I would also use my air horn to scare the animal away. If none of that worked, I’d take the bear spray out and begin to spray it as close to the animal’s face as possible. There may be residual bear spray that’d affect my child, but if I don’t get my child out of the clutches of the mountain lion, then a little bear spray in the face is the least of our worries.

If nothing worked, I’d attempt to climb the tree to scare off or attack the animal. If I couldn’t climb the tree, I’d call my husband over to help boost me up to the mountain lion’s level and begin an aggressive attack.

Once the mountain lion releases my child, we’d break out the gauze from our first-aid kit and begin to apply pressure. At the same time, we’d be rushing back to the parking lot/headquarters, all while one of us would continue to attempt to call for help. Our adrenaline would still be pumping so we’d be moving fairly quickly.

If service wasn’t available as we continued back to our Jeep, or we simply couldn’t reach anyone, as soon as we got to our Jeep, we’d call for help via our ham radio. Even as we reached out via ham, we’d be driving to the nearest facility that could provide medical attention, which may be a ranger’s station, hospital, or clinic of any kind. If at any point we were able to reach someone via radio and they couldn’t reach us, we’d ask where the nearest facility is to our location so they could direct us. In this situation, time isn’t our friend, and we need to find help immediately while continuing to apply pressure to the wound and treating it to the best of our medical knowledge.

Hiking with the family is a lot of fun, but there are also a lot of dangers that we need to be prepared for. Animal attacks may sound unlikely and are statistically rare — some sources say around 160 annually throughout the United States, but those 160 people probably never expected to be attacked, either. With proper research and preparation, anyone can be prepared for the worst-case scenario.

Conclusion

People forget that the wilderness is just that, an untamed area of our world where survival of the fittest is the norm, and the natural order of things is for larger animals to prey on smaller ones. As we push further and further into rural areas, the hunt for food can often turn to human victims. No one ever thinks it’s their turn, but assume that the hills have eyes and prepare accordingly for animals that have a level of stealth and strength honed by millennia of evolution.

Success and survival in this case, or in any other animal or mountain lion attack scenario starts with comprehensive preparation before going afield. The careful selection of the right gear for the adventure is also critical, and being ready to take appropriate and decisive action when the unthinkable happens is paramount to surviving any animal attack. Know the potential dangers in the outdoor environment you plan to explore, be prepared, never take Mother Nature for granted, and enjoy the journey.

Morgan “Rogue”

Morgan “Rogue”

Morgan “Rogue” resides in Texas with her husband, daughter, and two dogs, with their second daughter on the way. Her family is always venturing into the wilderness and challenging themselves, as well as others, to love the outdoors. Through Rogue Preparedness, she works toward making the world a more prepared place, where people can feel confident in knowing that they possess the skills, knowledge, and items to get them through any emergency or disaster. She educates and entertains on her YouTube channel, website, and social media platforms, as well as in-person events held in Texas. You can find Morgan at roguepreparedness.com

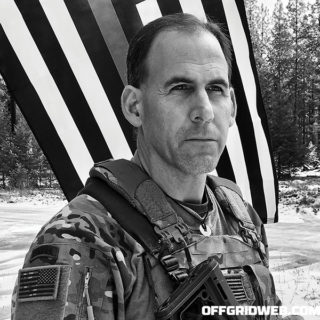

Lt. John Nores

Lt. John Nores

Lt. John Nores (ret.) is a worldwide conservationist who has investigated environmental and wildlife crimes for 28 years as a California game warden and was awarded the Governor’s Medal of Valor for lifesaving and leadership efforts in 2008. Nores codeveloped and led the California Dept. of Fish and Wildlife’s Marijuana Enforcement Team (MET) and Delta Team (the nation’s first wilderness special ops unit and sniper element) aimed at combatting the marijuana cartel’s decimation of our nation’s wildlife, wildlands, and waterways. His latest book, Hidden War: How Special Operations Game Wardens are Reclaiming America’s Wildlands from the Drug Cartels highlights the team’s first six years of operations (2013 to 2018). Nores hosts RecoilTV’s Thin Green Line film series, cohosts the Thin Green Line and Warden’s Watch podcasts, and has been featured on several other podcasts.

STAY SAFE: Download a Free copy of the OFFGRID Outbreak Issue

STAY SAFE: Download a Free copy of the OFFGRID Outbreak Issue

No Comments