RECOIL OFFGRID Survival What If You’re Stuck in a Country Consumed by Political Turmoil

In This Article

It’s 2021 and many travel restrictions have lifted, offering people the opportunity to finally vacation internationally or visit other countries for business. Although it may have seemed like COVID was the only big concern when considering foreign travel, political turmoil can be just as contagious, unpredictable, and deadly as a conventional disease. Whether it’s the 8888 Uprising in Burma, 2016 attempted coup in Turkey, or recent presidential assassination in Haiti, situations can often unfold with little to no ability to estimate how it’ll impact national stability or treatment of foreigners.

Despite whatever planning you may have thought was adequate and thorough, your overseas travel may put you in the wrong place at the wrong time with only local resources to assist you in seeking safe haven. If you were stuck in a country that was suddenly reduced to chaos and the political rhetoric on the ground shifted blame to people of your nationality, how would you deal with potentially being labeled as a threat to the local government? Risking capture could result in interrogation, imprisonment, or even death.

Situation Type: Traveling Abroad

Your Crew: Yourself

Location: Southeast Asia

Season: Autumn

Weather: Humid; high 88 degrees F; low 63 degrees F

The Setup: You take a trip to Southeast Asia, a region you’ve traveled to many times in the past, to visit a plant that manufactures goods for your company. You plan to spend a few days visiting with your associates there, but you only have a marginal understanding of the local language, culture, laws, and key facilities, such as the American embassy. Protests have been frequent in the area during the last few weeks, and most have culminated in a few arrests before crowds were dispersed by police. This time feels different. Over the next few days, you begin to worry as police presence and the size of the protests seem to be escalating. The national news is continually blaming Western influence for the corruption and continued civil unrest. As if the guilt by association couldn’t get much worse, you’re also informed that all foreign diplomats are in the process of being expelled, embassies are being forced to close, and all foreigners — particularly Americans — are being explicitly named as subversives by the government.

The Complication: You wake up a couple days before your flight home to the sound of gunshots outside your hotel. Peeking out your window, you can see a column of military vehicles moving down the street, with uniformed troops marching alongside. Citizens are fleeing in fear. You turn on the TV, and the American news channel in your hotel room is saying that protests have morphed into an attempted coup that was crushed by the government. In response, the government is now detaining and questioning any foreigners.

After speaking with a few other Americans in your hotel, you learn that the government is intermittently shutting down internet access, similar to what went on during the Arab Spring and more recently in Myanmar. You’re also informed that secret police are beginning to monitor hotels for foreigners, and that access to the airport has been compromised by a military blockade. As an American, you fear your passport may put you in jeopardy. The prison conditions are terrible, and you’re aware that many people have been incarcerated in this country indefinitely without even having a trial.

What do you do? Who can you call? Do you have any rights whatsoever? The language barrier proves an even greater obstacle to navigate. What steps can you take to explain the situation believably and receive assistance from family, the State Department, or anyone else who can help you out? We’ve asked security expert Danny Pritbor as well as international media correspondent Miles Vining for their recommendations on how to deal with the situation.

Years ago, a mentor and longtime friend shared a quote that stuck with me throughout my years of service: “Movement without observation equals death.” At the time, the context was in reference to a low-light firearms course, where he was explaining the constant need for situational awareness. To be effective in the tactical environment, you need to process and prioritize data rapidly — in other words, stay “switched on.” As my career progressed, and the areas of operations shifted from domestic to international, I realized the saying couldn’t be truer. But based on my experiences, I’m going to add to the quote, “Movement without observation and preparation equals death.” I, along with countless others serving in operational roles, often in hostile environments, have learned some hard lessons, usually after the action takes place, and many times after lives are lost.

Prior to an overseas trip, I conduct a risk assessment. Using open-source satellite imagery, I get an overview of the area. First, I locate my hotel, the airport, and worksite. Secondly, I start to identify where my friendly locations are, like the U.S. Embassy or allied embassies. Other key locations are hospitals, alternate airports, or maritime ports.

I identify my primary routes and secondary routes to frequently traveled locations. I research information on activities such as crime, terrorist actions, and government/civil unrest. My focus is initially on the city or town I’ll be traveling to, then working outward to the provinces and country. I pay close attention to the entire region as well; neighboring countries may have turmoil that can bleed over and affect the area of travel. By taking these steps, I establish where and when these significant acts are taking place and pinpoint the highest risk. Then, I can take steps to mitigate the risk.

For example, I advised a group of college-aged individuals who would be traveling through parts of North Africa. They wanted to take the train, which was the common mode of transportation. There was a low to moderate threat of terrorist activity in the region. After the group attended our travel security course, they quickly understood that the train would make them vulnerable to “time and place predictability” as well as place them in a crowded environment where women are often sexually assaulted. Because they understood the risk, they developed an alternate plan which allowed for greater flexibility in how and when they traveled.

Now that there’s an understanding of the risks and situational awareness of the environment, I develop what’s called a “base monitored movement plan.” It’s pretty simple: I have someone back home who is my base monitor. I share my communications and travel plans with them. For example, I’ll check in every 24 hours at 6 p.m. local time on primary communications, which I’ll have listed as a text from my cell phone (alternate is an email; contingency is satellite text via Garmin inReach Explorer+).

For any missed check-ins, I establish a shorter window. If I miss my 6 p.m. check-in, I attempt again as soon as possible; but if it’s midnight with no contact, my base monitor will need to consider calling the listed emergency contacts of the area I have listed in the plan. When civil unrest takes place, airports are the first to shut down. Haiti is the prime example of this and Egypt during the Arab Spring. I build options for alternate means of departures from the country. Along with my alternate communications plan, I take into consideration establishing evacuation plans which include air, land, and sea (or other body of water) options.

What I typically do is have a pro word — a shorthand procedure word representing a predetermined meaning — designated for each city and/or evacuation plan. Should I need to affect a specific plan, I’ll send the pro word to my base monitor, and they know which plan is in effect. That way I keep my travel plans off communications.

As a traveler, I carry two lines of gear. In principle, each line consists of the following categories: medical, communications, and personal defense. I add to these, but don’t omit any of the three. This system has served me and others well by ensuring an overlap of these critical items. If I were considered a resident or living abroad, I’d expand my lines of gear to a third (vehicle) and even a fourth (residence) line. Important note: the lines shouldn’t appear military/tactical, so leave the MOLLE and Velcro-covered bags at home.

The first line is carried on my body. For medical, I carry a pressure bandage, usually a 4-inch Israeli bandage, stripped out of the package. I remove it from the primary marked packaging to give it a sterile look (no government markings) to avoid any questioning should my bags get searched. The bandage is packaged in a second, clear unmarked wrapper to keep it clean. I also carry a CAT Tourniquet in a non-tactical color (i.e. orange). Both these items are carried in an ankle med kit and/or cargo pockets.

My primary form of communication is my cell phone. On it, I have my navigation and various communication applications. These apps require cell signal or Wi-Fi. Many of the navigation apps can be used offline, without cellular signal. (We could go down a rabbit hole with digital security, so that’ll be left for another time.)

Carrying weapons abroad is always tricky. Personal defense gear will have to be a personal decision; choose items that can be explained and have a plan to do so. I try to stay within the law of the land, making every attempt to avoid scrutiny when crossing the border. I carry a SureFire Tactician flashlight and often opt to travel without my name-brand fixed blades. Once on the ground, I’ve been known to head over to a night market or hardware store for items such as a screwdriver or paring knife. I make a sheath out of cardboard, duct tape, and string (for a lanyard). These items can be disposed of in a hurry, or if questioned, I can provide a reasonable explanation as to why I have the items. The bottom line is I have a plan for personal defense.

It’s important to note, I discreetly stash my passport in my first line. This is just in case I get separated from my second line/go-bag. During stressful situations people have been known to leave go-bags behind. I usually bring emergency cash ($2K to $5K) and/or items that can be used to barter with. Credit cards will not be useful during lawlessness and disorder. These items are hidden away in my first line.

My second line is a medium-sized backpack or messenger. I carry additional medical, communications, and items for personal defense. For medical, a full-sized individual first aid kit (IFAK) along with a booboo kit (Band-Aids and over-the-counter meds). Communications consists of Garmin inReach Explorer+ (satellite texting unit), spare batteries, charging cables, and 20,000 mAh (minimum) external battery pack. Additionally, I have a couple of headlamps, a spare flashlight, batteries, snacks, baby wipes, gloves, water purification tablets, copies of my passport/documents, compass, and rain gear.

An often-overlooked aspect of foreign travel is “denying evidence.” Understand that your social media footprint provides a great deal of information about who you are, what you do for a living, and where you stand politically and religiously. If you’re detained by the local authorities, and questioned about why you’re there and who you work for, what will they find on your social media feed? Many cultures operate on what is called a “shame and honor” system. Will your feed depict you as an honorable person? I want my social media to support my reasons for being there.

If questioned about who I am and what I’m doing there, I should be able to provide a short, legitimate statement (SLS). For example, “I work in the textile industry, and I am visiting companies A, B, C, regarding our manufacturing needs.” If I’m in the textile business, then my feed should reflect that. No political statements, pictures of the wild night of partying, provocative behavior, and statements that would be considered disrespectful to the local religion. I’m mindful that I’m in their country and U.S. civil rights no longer apply. In other words, I have a solid “backstop” and show that I’m honorable.

If my business requires multiple trips to a location, I work toward improving my initial plans. Once on the ground, I hone in on the patterns of life: what government officials dress like, what the checkpoints look like, where the checkpoints are located, traffic patterns, interactions between locals, just the day-to-day routines. The purpose is to determine what “right” looks like, so I know what “wrong” looks like. I build my network of strategic relationships, determining which locals can be of assistance, especially should I need to implement an evacuation plan or need a safe house.

Perhaps my contacts in shipping at the textile factory can assist with a water evacuation via the port if necessary or a trusted official can help me lay low for bit. I work to make sure the evacuation plans developed back home are a reality on the ground. This will require familiarization of routes and scouting key areas. As my network of strategic relationships expand, I work to develop additional emergency communications plans and possibly implement a mesh network such as GoTenna Pro or similar.

If I’m located near an embassy, I arrange a meeting with the Regional Security Officer to introduce myself and explain my travel and/or company’s purpose. Just as with the local relationships I mentioned, I work on building relationships with the embassy staff to get invited to functions and stay informed.

Don’t ignore the danger signs! There’s usually a buildup to civil unrest and critical incidents. If you have your head on right and paying attention, you should be able to make your exit prior to any major shutdowns or disruptions. If you find yourself pinned down in your hotel room or somewhere in the “open,” you need to determine the best option based on the information on the ground. Remember, movement without observation and preparation equals death.

In the tactical community, there’s a great deal of emphasis on the hard skills, like various shooting and combative programs. There’s nothing wrong with having these skillsets, but keep in mind hard skills will be used after the “bang” takes place. For today’s world traveler, there should be an equal amount of time dedicated to honing soft skills, which focuses on mitigating risk and avoidance. A few of the topics to study are: Situational Awareness, Medical/TCCC, Surveillance Detection, Active Shooter Response, Security Driving, Actions on Contact, Digital Security, Building Risk Assessments, and Base Monitored Movement plans. Learn more about how to train for these in my author bio at the end of the article.

If knowledge is the lightest piece of gear one could put in their travel bag, then interpersonal communication skills has to be the second lightest. The most important point I’d like to stress is that the crisis prompt is essentially a man-made problem that requires human solutions. If you can’t build tangible relationships and connect with other people on a personal level, no amount of survival gadgets are going to get you out of a bind of this magnitude in a foreign country.

One thing we shouldn’t fool ourselves with is being some sort of Jason Bourne or James Bond figure who sneaks through the shadows of a foreign locale. Looking to historical precedent, it needs to be pointed out that for many of the great “Western” explorers who have conquered Everest (Edmond Hillary), crossed the Empty Quarter of the Arabian Peninsula (Wilfred Thesiger), or ran humanitarian missions into war-torn Burma and Syria (David Eubank), there has always been an equally competent or even more ambitious local counterpart/guide who has helped to navigate the human and terrain environment. This is why every successful news crew in the world has behind-the-scenes “fixers” whenever they go into foreign countries.

So, when it comes time to deal with a crisis, don’t think for one second that you won’t need the assistance of the local populace. In fact, to not take local cooperation into account is to doom yourself to failure. Whether it’s an actual guide, a driver getting you across the city, a shopkeeper to provide you with food and water, or a friendly translator, you’re going to have to negotiate, barter, explain, and even beg with people who don’t share your language, nationality, religion, or values. How successful you are at this process could mean the difference between going to a foreign jail or going home.

For communications, I usually want to have several types of data and cellular service. Ideally, I have a local SIM card, an international SIM card, and preferably two cell phones. One phone I like to call my “dirty” phone, where I download and interface with all the host countries’ applications and registrations. The other one, my “clean” one, I try to keep separate with my personal information, my more confidential calls, etc. Beyond cellular phones, some very good devices that exist are satellite pagers where I can get GPS coordinates, send SMS messages via satellite, and even push preset emergency messages to designated recipients. Spot X is one such company that has very economical packages. For a full communications capability, I no longer need to lug around a bulky Pelican case with the ubiquitous folding antenna sat phones that barely work half the time. SatSleeve from Thuraya is a very compact clip-on device that simply connects to my iPhone or Android device via Bluetooth. But with these two types of devices, I need to take into account the fact that, if I’m held in a foreign country already suspicious of my intentions, finding unregistered satellite communications technology in my luggage is a solid indication that I’m some sort of spy.

In regards to more gear, I like to be as efficient and self-sufficient as possible. My electronics need to be compatible with the host country’s outlets and voltage; if I can power them myself via solar chargers that’s a plus. I like to bring a repair kit consisting of Shoe-Goo, gaffer’s tape, and a sewing kit to fix small tears and issues that might come up. But much more important than gear, I need to realize what I have, and be able to replace these capabilities in-country with local amenities. I should be browsing local stores to see what might work better or is equal in comparison to the kit I’m bringing in. Amazon isn’t going to be there for me when I need it the most. I don’t want to be a hostage to my equipment, and I need to adapt when items fail.

With communications, I have to assume that everything I’m transmitting is being bugged, censored, or recorded some way or another. Applications such as Signal are great, but it doesn’t make a difference if the host country is able to covertly download software to your phone that monitors your keystrokes. Prearranged brevity codes are good to develop with family members and friends, but they have to be kept simple and dummy proof. For example, one brevity code I’ve used with my spouse is in referencing the third floor of our apartment if I were to get into a bind, but still have communications. Of course, our apartment doesn’t have a third floor, it only has two, but that’s the point. I can call her and say, “Would you mind looking through my hockey sticks in the third-floor storage room,” in response she could make up the flow of the conversation, but instantly realize that something is very wrong in my part of the world.

Whenever I’m in a new location overseas, I need to try and seek out whatever environment I’m in, both the physical and the human terrain map. For the human terrain, I want to know who is in the area every day. The security folks, restaurant employees, gym employees, and receptionists. Can I establish a rapport, even a friendship that might be able to help me? Knowing my physical environment is critical as well. What roads, pathways, buildings, and structures show up on maps that don’t exist anymore, and vice versa. Offline mapping applications such as Maps.Me, or OsmAnd are fantastic when the network is down, but a thorough scouting should still be in order. On one occasion when I was climbing a hill in China, I came cross a patchwork of small-gauge power lines anchored on steel poles only knee-high. Sure, I could low crawl underneath them, but that wouldn’t have been an efficient route if I needed to get over that hill in a hurry with gear. Satellite images of the hill showed a bare surface.

When I’m staying in an unfamiliar sleeping location, I want to consolidate my belongings in a way that still allows me to efficiently get to them and use them, but also so that I can easily work from them. I can’t live in a state of hyper-preparedness, but I also don’t want to get caught with all my overseas worldly belongings littered across a hotel room. What I try to do is minimize the number of places where I keep my belongings. I pick three or four locations in a room and stick to them — the closet, the bathroom, my bedside table, and maybe a desk. I use my existing bags as organizers and wardrobes for my belongings.

Having a designated go-bag is definitely nice, but let’s keep things in perspective here. I’m in a foreign country, I need all my belongings. I don’t want to just survive; I want to thrive with all my equipment. Maybe I bounce out of that hotel room with my sweet go-bag and end up having to hunker down somewhere in-country for weeks at a time because the borders are closed due to the volatile political situation. If I have the liberty of 20 to 30 minutes in my room, wouldn’t I have wanted to at least attempt to gather the rest of my belongings, which should’ve only been in several locations to begin with?

That being said, I need to come up with a realistic evasion logistical plan. If I’m starting with no time at all, I can only leave with what I have on my person. That should be my passport (and a small laminated copy thereof in another location on my body), shoes, what I’m wearing, an ability to see at night, whether that’s a headlamp or a handheld light (which also works nicely as a blunt force weapon), my mobile device and a way to charge it, and a jacket (which can double as a blanket). This sounds simple, but let us imagine a scenario where you’re in your hotel or around the corner from it, and you cannot access your room due to a hostile takeover, a police barricade, or an angry mob rampaging and looking for foreigners (CWO Bryan Ellis was killed in this manner during the 1979 U.S. embassy riots in Islamabad).

Our second time slot is going to be that several-minute window where we can get our go-bag, throw a couple extra necessities in, and scram out the door. Now, we have a more nuanced approach to how we can live out of that bag for a limited period of time.

Our third time slot will be half an hour to perhaps an hour. You know a crisis is ongoing and you have to leave. If we can leave with all our belongings, let’s try for that. If we’re limited to our go-bag and maybe a secondary small bag, that works too. Now we can prioritize what we can jettison or keep when it comes to space. This would also be a good time to organize bags on priority, starting with what’s on your person first. If you have to jettison all your bags, what do you need to ensure stays with you? If you have to jettison one or two, which ones are they going to be, based on priority? We probably don’t want to chuck our laptop, power banks, and hard drives, but that suitcase with souvenirs, extra clothes, or items we can probably get locally anyway could probably go.

When I’m in a foreign country that might be third-world, totalitarian governed, and even at peace, I’m working with the notion that everyone I meet already assumes I’m a spy, an agent, or some kind of intelligence officer for the United States. I’ll actually never be able to rid myself of this assumption. But I do have the ability to either lessen the spy bias or increase it. By owning or carrying tactical items — even something as innocent as a C-A-T tourniquet, for example — the assumption of being an agent has been heightened. If I try not to lie and try to be honest with authorities, the spy assumption might be relaxed. How I present myself through my physical belongings, demeanor, attitude, and actions will bear a tremendous amount of weight in the minds of those whose authority will determine whether I can get on a plane back home or rot in an overcrowded jail. Now isn’t the time to be coming up with a cover identity or a supposed origin story.

When I’m questioned, I want to stick to the facts. I don’t need to be opining about which side I support in the country, what I think about the deteriorating situation, or the United States’ role in the mix. What’s my business, what I am doing, what items I’m carrying, where I want to go, and how I want to leave.

Bribes are an incredibly tough subject overseas. They’re just as likely to get me in trouble as they’re able to get me out of trouble. Especially with bribing official authorities, because that adds more fuel to my case of being a no-good foreigner in someone else’s country. If I were to attempt a bribe, I’d try to relegate it to small, tangible actions that can be completed soon and in my vicinity — bribing a guard to open a gate, a ticket manager to change a ticket. I’m in no position to make open-ended, complicated, behind-the-scenes negotiated agreements that’ll lead to my release. This isn’t my turf, and I don’t know the human terrain with the right relationships in positions of power. What kind of language I use is especially key as well. Many authorities who take in bribes regularly don’t like to refer to it in such crass terms. Instead of saying, “Can I pay you to open this gate,” maybe try, “I would like to give you a bonus for your hard work,” or “If you can help me with something, I can monetarily return the favor.” An outright bribe of “I’ll pay you a certain amount to do this for me” might end up insulting someone severely. Put on your best thinking shoes and work some diplomacy.

When looking at international organizations for help or escaping to neighboring countries, I’ll have to tap into pre-existing networks somehow. There are numerous emergency travel insurance companies out there that work in ways that can be very beneficial. This doesn’t mean they’ll be fast-roping into your compound with an armed extraction team, but it does mean they might be able to arrange plane tickets with travel agencies they’re friendly with, or have folks in those countries come and provide places to stay or advice. Global Rescue and Ripcord are two such companies, but there are several out there.

The key to any of these situations is going to be your intuition and people skills. Work through some of these scenarios with an assumption of being stripped of everything you know apart from your clothes, then revisit how you would handle that situation. The gear is great, but your interpersonal skills need to be one step ahead. Stay cool, calm, and collected, build up your sources, verify your news, act with confidence, and go with your intuition.

Pay attention to escalating problems in any area you plan to visit. A population’s confusion and overall disposition about a situation can be easily exacerbated by mass media and sudden turmoil. Check the U.S. State Department website for travel advisories prior to venturing abroad. Having redundant forms of communication to relay information to anyone back home, multiple escape routes, and friendly local contacts are just a few necessities that could mean the difference between survival and incarceration.

No one needs to know anything about you other than what you look like to form inaccurate and dangerous assessments that could put your life in danger. Although the reality may be that regional unrest has nothing to do with you personally, the perception on the ground may be that it does. Don’t assume this situation is only specific to other countries. You may have to apply these lessons to a domestic situation if civil stability continues to decline.

[Editor's Note: Illustrations by Cassandra Dale.]

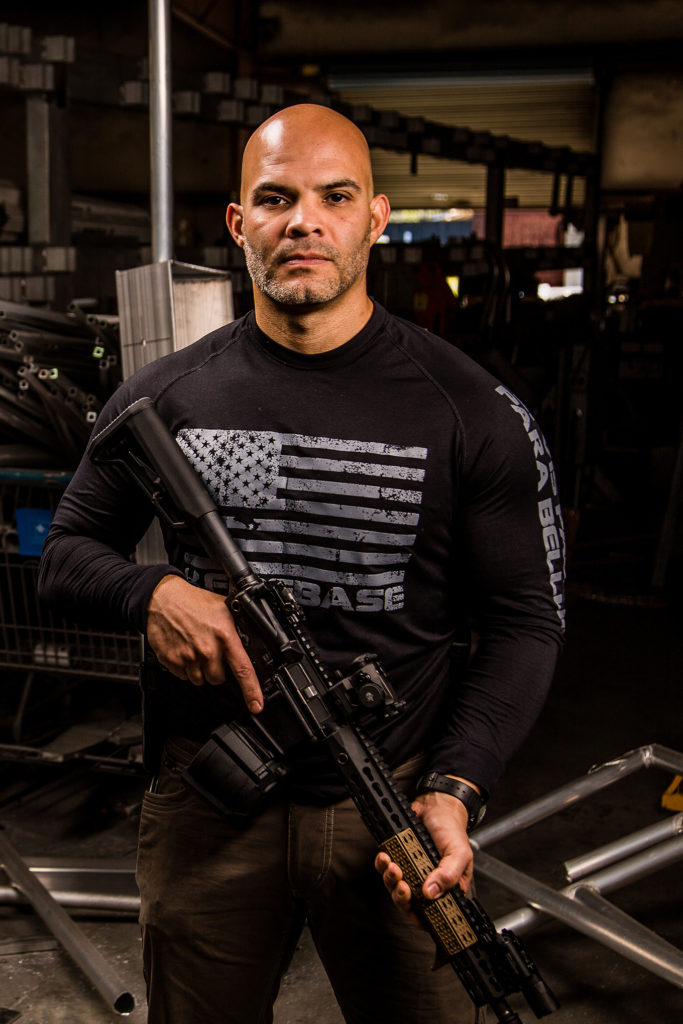

Danny Pritbor, director and owner of Firebase Combat Studies Group, currently serves as a Department of Defense contractor. Danny’s career spans over 29 years with service as a U.S. Marine, law enforcement SWAT officer, Department of Energy and Department of State contractor, federal agent, and private security consultant. He’s served worldwide in various war zones and high-threat areas. His company partnered with Panoplia to develop a nine-hour, online training program called Soft Skills and Tactics. It consists of three parts, nine lessons with 45 topics covered. In conjunction with the online course, Firebase offers a two-day security training program that consists of lecture, hands-on, and a field training exercise with stations that push participants to take charge, make decisions, and problem solve. For more information on the online SST program, please visit to panoplia.org. You can also reach Danny at firebasecsg.com.

Danny Pritbor, director and owner of Firebase Combat Studies Group, currently serves as a Department of Defense contractor. Danny’s career spans over 29 years with service as a U.S. Marine, law enforcement SWAT officer, Department of Energy and Department of State contractor, federal agent, and private security consultant. He’s served worldwide in various war zones and high-threat areas. His company partnered with Panoplia to develop a nine-hour, online training program called Soft Skills and Tactics. It consists of three parts, nine lessons with 45 topics covered. In conjunction with the online course, Firebase offers a two-day security training program that consists of lecture, hands-on, and a field training exercise with stations that push participants to take charge, make decisions, and problem solve. For more information on the online SST program, please visit to panoplia.org. You can also reach Danny at firebasecsg.com.

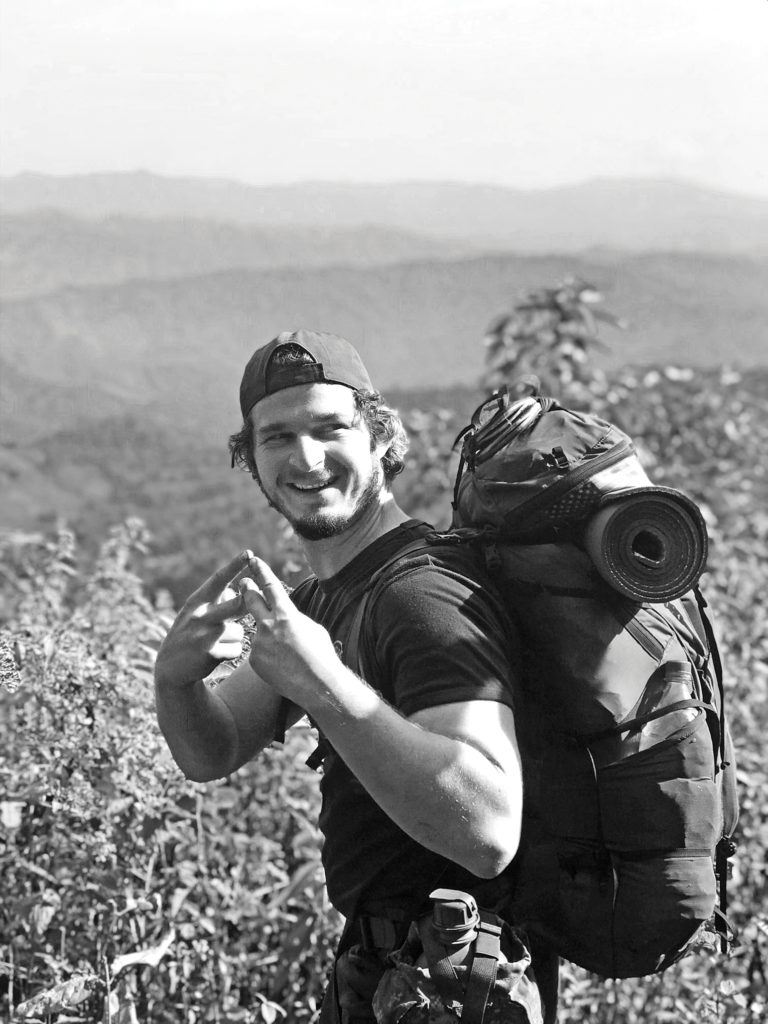

Miles Vining spent his childhood and teenage years growing up in Thailand, Burma, and Malaysia, returning to the region after his service in the Marines to work with an international relief group that works in conflict zones in Iraq, Syria, and Sudan. He also worked in digital media with a local Afghan company in Kabul. Beyond RECOIL, his work has appeared in Small Arms Review, The Firearm Blog, the TFB TV YouTube channel, and Strife Blog. Currently, he’s the editor of Silah Report, an online resource group focused on researching historical and contemporary small arms and light weapons from the Middle East and Central Asian regions. Learn more at www.silahreport.com.

STAY SAFE: Download a Free copy of the OFFGRID Outbreak Issue

STAY SAFE: Download a Free copy of the OFFGRID Outbreak Issue

No Comments