In This Article

Editor’s Note: The following article was first published way back in Issue 1 of our magazine, and provides a broad entry-level overview of bug-out planning. Even if this info seems basic to you, it can serve as a simplified introduction for those who may have less prepping experience or no experience at all. It’s also a great reminder of the fundamentals, even for longtime preppers.

Natural disasters. Terrorism. The Apocalypse. There are dozens of disasters (a few fictional, the rest very real) that have given people cause to prepare for a bug-out scenario. Just remember, being paranoid is not an effective survival skill, but awareness, on the other hand, is. We must understand that being aware and prepared is simply being responsible.

So, no matter your level of experience or training, incorporating the following into your bug-out plan will provide you with a good starting point to survive almost any situation:

- Preplanning

- Bug-out bag

- Gear

- Evacuation plan

- Communications

- Security

The following is a primer on how to create your own bug-out plan based on these elements. Even if you already have an emergency plan in place, it’s always good to review it to see how to modify, adapt, or improve it for a variety of situations.

Preplanning

Start with honesty: Self-awareness is the single biggest factor. Make a list of the things you know you’re good at. Do you have first aid and CPR training? Are you well-organized? Do you have special skills? Practicing and improving your skills is all part of your preplanning. People buy a BOB (or bug-out bag), buy a map, pack some food and water, and they think they’re OK, when it’s TEOTWAWKI (the end of the world as we know it). Don’t be fooled by a false sense of security just because you have gear.

Adjust your attitude, cry baby! Have a good attitude. Yeah, no sh**, it’s going to be tough. By having the right mindset, you’d be surprised at what you can accomplish. It also helps lift the morale of those around you.

Get fit: What kind of physical shape are you in? Don’t think it matters? Put on your BOB and walk nonstop for 20 blocks. Anything hurt? How fast did you go, safely? Proper nutrition and regular exercise go a long way in managing stress and developing physical endurance.

Bug-Out Bags (BOBs)

There are many BOBs (sometimes called go-bags or survival packs) on the market. The truth is, in certain examples, it doesn’t matter how much you spend. Your practice and basic survival skills can turn an inexpensive bag into one that is more capable than its expensive counterpart. Here’s a brief description of the three types of go-bags:

The 24-Hour Bag: This small pack’s main function is to provide a few supplies for your immediate situation. This should include, but not be limited to, the following: knife and/or multi-tool, disposable plastic poncho, emergency Mylar blanket, small LED flashlight/headlamp, first aid items, high-calorie energy bar, water bottle, and signaling items such as a whistle.

The 36- to 72-Hour Bag: This is the most popular size on the market today. Most people think that a go-bag needs to be tactical-looking. However, many sport backpacks today are also multi-functional. Just make sure it fits comfortably when it’s filled. The supplies should last through three days.

Sustainability Bug-Out Bag: The major difference here is the added equipment, such as fishing kit, rifle and ammo, radios, solar panels, and so on, based on your skills and knowledge. The more stuff you carry, the heavier the bag. So, you would think a bag like this would be much bigger than the other two; the truth is the more skills you have, the less stuff you need. This is what it means to be self-reliant.

Survival Gear

As you pack your BOB, keep in mind the three 3s: three minutes without air, three days without water, and three weeks without food generally puts you in life-threatening territory. Here are the basic items you should have for your go-bag:

Bag: It should be reasonably comfortable when full and have adjustable shoulder straps, along with lumbar and sternum straps. The weight should be carried on the hips and not the shoulders. (For more on survival backpacks, see: “Back-Up-Pack” from Issue 1.)

Shelter: Most people think about bringing a tent. But, that adds a lot of weight. Instead, think about using a layer system. I have a lightweight waterproof bivy sack, lined with a Mylar bivy sack, followed by a wool blanket. The innermost lining is a 100-percent silk cocoon mummy liner. Contractor garbage bags or compact tarps can also go a long way and can be used in a variety of ways, especially with some paracord to form a quick ridgeline for an A-frame or lean-to shelter.

Water: There are many types of portable water filters and purifiers available. Don’t buy the cheap stuff. Most importantly, look at the ratings. You should have a filter that has been independently tested and proven to meet the NSF/ANSI P231 Guide Standard Protocol. Anything else and you might as well use your sock, which I don’t recommend, especially after a long hike. For the on-the-move type, straw-style filters like the Lifestraw or Sawyer Mini are handy. Water treatment tablets, drops, and pure household bleach provide the ability to kill the pathogens; however, they don’t filter the water. Also, having an extra stainless steel water bottle will help with the boiling process after collection, as well as act as portable storage within your pack. This enables you to collect, filter, and carry water. (For more on filtering water, see: “H2-Uh-Oh” from Issue 1.)

Fire: Have several different ways to make a fire, such as waterproof matches in a waterproof container, lighters, stormproof lighters, ferrocerium rods, flint and steel, and so forth. Don’t rely on a single source to produce fire.

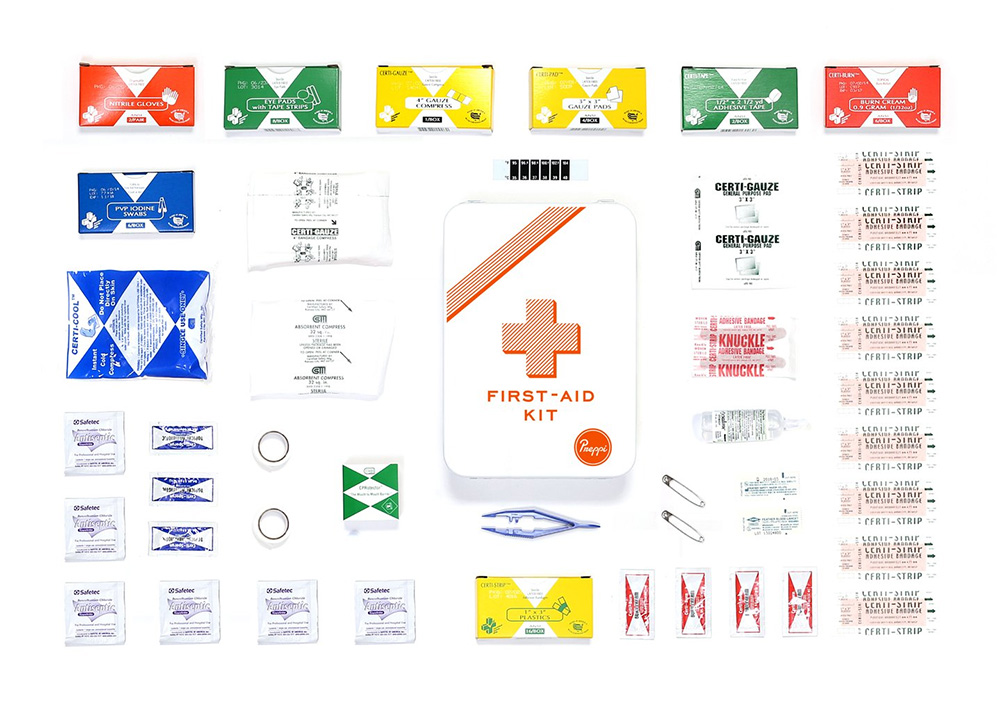

Medical Supplies: A basic first aid kit is a must. So are medicines or prescriptions that you or your loved ones need. This includes extra contacts and glasses. I have added a suture kit within my first aid kit, as well. (For more on first aid kits, see: “First Aid” from Issue 1.)

Clothing: Dress in layers. I have 100-percent silk long underwear and 100-percent wool long underwear in my bag, along with a wool hat, wool socks, and a pair of gloves. Raingear not only lets you stay dry, but it also provides protection from the wind and enables you to sit on wet ground. This can include a change of footwear.

Food: There are many different types of survival dehydrated foods on the market today, but be careful because most of them are loaded with sodium. You should have enough quality food in your pack to get you through the worst part. Once you run out of food, you may be able to scavenge for food in abandoned urban areas, but it’ll be a good idea to know your plants and how to hunt and trap. (For more on food, see: “Brown Baggin’ It” from Issue 1.)

Signaling: If you want to be found, think of bright contrasting colors, signal mirrors, flares, and strobes. Along with your signal fire are just a few simple methods to get noticed.

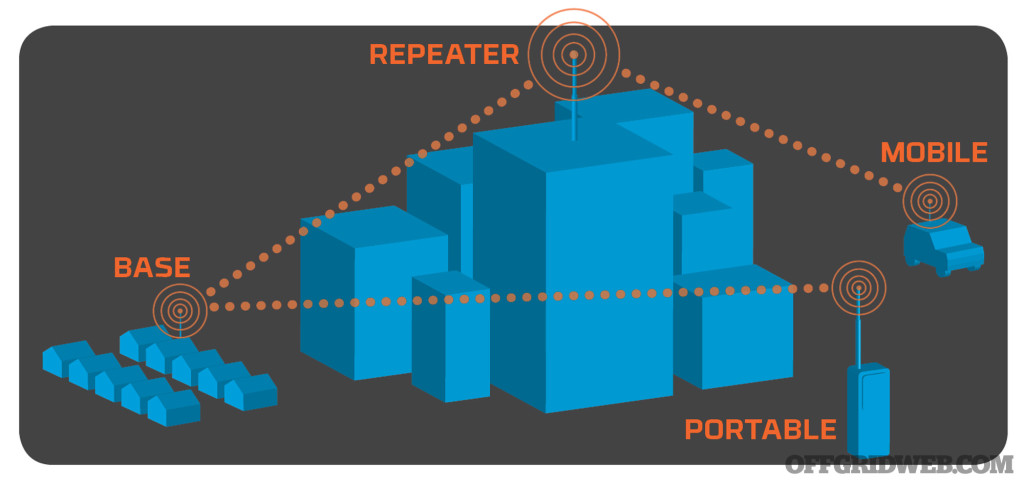

Communications: At TEOTWAWKI, your mobile phone will most likely turn into a paperweight. Consider walkie-talkies, two-way radios that are GMRS, CB radios, or ham radios. You’ll also need the ability to charge them, such as with lightweight solar-powered chargers. Make sure that the batteries of your electronic devices and flashlights are of the same type, so you can swap them out while the others are charging.

Organization: Each item should be placed in its own waterproof sack before being packed within the bag. I use different colors to indicate the contents. You should be so familiar with your bag that you can retrieve items in complete darkness.

Personal 411: Have all of the prudent names, phone numbers, and addresses of your loved ones on hard copy. Also consider taking your financial records, medical records, birth certificate, and passport.

Navigation: Bring a compass and three types of maps: a city street map, an atlas with city and surrounding area roads, and area topographical maps. Having a GPS is beneficial—until you lose signal or run out of power.

Covert Cache

A go-bag can only hold so much. So, you might want to consider stowing supplies, such as food, water, and clothing, in and around your meeting points. What do you have in your car? What’s at work? What do you have at school? One caveat: You have to have complete trust in the people who know of the locations of these caches.

The Event

It’s timing and manner in which your SHTF plan is activated that will determine its overall success. So, how do we determine the timing? It’s called awareness. Be aware of the signs of an impending disaster or threat.

A crisis can sometimes occur with little to no warning at all. Sometimes, we are given the luxury of time. The event itself will dictate your response. Crisis response requires a crisis mindset. Breathe and remain calm. Then, ask yourself these nine questions:

- Am I OK and is everyone else OK?

- What happened? (Get as much intel about the event as possible in the shortest amount of time.)

- Is it safe to be here?

- If I need to move, how far and how fast?

- Where is the wind blowing? (Watch for airborne threats.)

- What do I have with me?

- What time of year is it? (Winter will dictate a different game plan than summer.)

- Am I alone? (If not, find out who is nearby, what their condition is, and whether they need to be moved.)

- Based on the event, which direction should I go next?

The Exit Plan

Escape routes will be determined based on the event. So, give yourself navigation options. Lay a map on the kitchen table, and choose rendezvous points that everyone in your family is familiar with. You will choose points in all the cardinal directions (north, east, south, and west). For each direction, you should have at least three options: right in the neighborhood, at the edge of the city, and outside city limits.

Think about the paths that most people probably wouldn’t use. We are creatures of habit, so most most of us will travel in large groups during a mass exodus, which also means increased risks and threats. Find lesser known or even secret paths. Avoid bottlenecks. If there’s heavy traffic in a location during rush hour on a normal afternoon, you can bet there will be far more in a disaster.

Make it a habit to go to and come home from work, school, and play in as many different ways as you can. Get to know your city and its many different avenues, alleyways, and those little out-of-the-way points. Think about what’s available on the landscape that you could possibly collect along the way. Pay attention to your environment (in other words, be aware!).

Communications

Mobile phone networks will most likely not work in a long-term SHTF scenario, but within the first few hours after an event, you might get lucky. If so, you can initiate the plan with the most simplistic messages. For example, use three characters such as “A1A.” The first character refers to direction (A equals north, B east, C south, and D west). The second character means path of travel (1 means fastest and easiest, 2 means second fastest, and so on). The third character stands for rendezvous site (A is closest point, B is edge of city, and C is outside of the city).

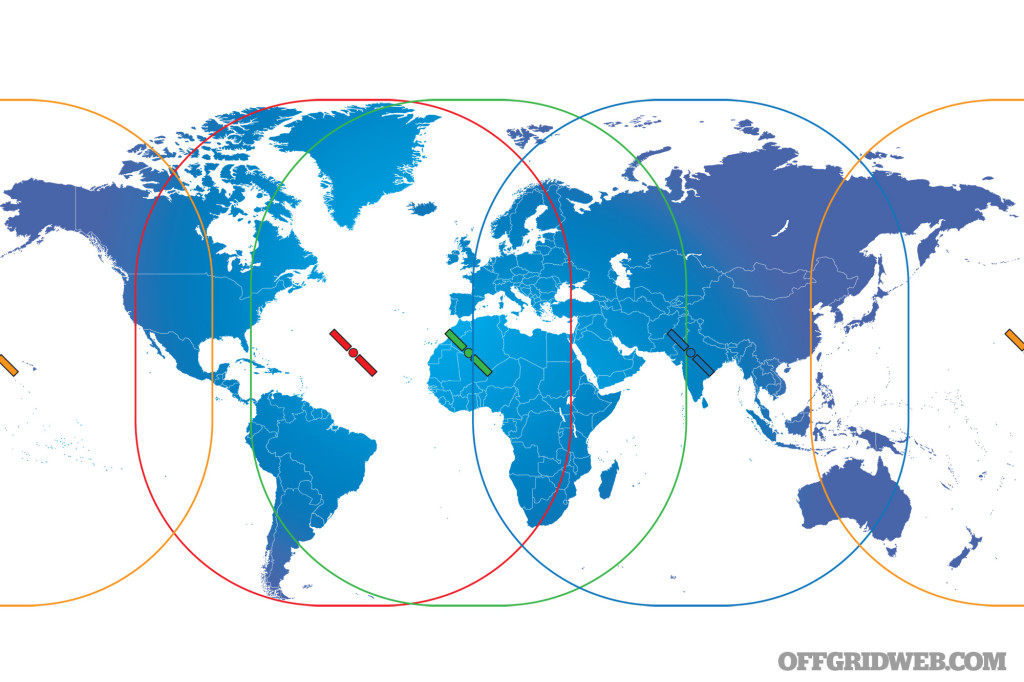

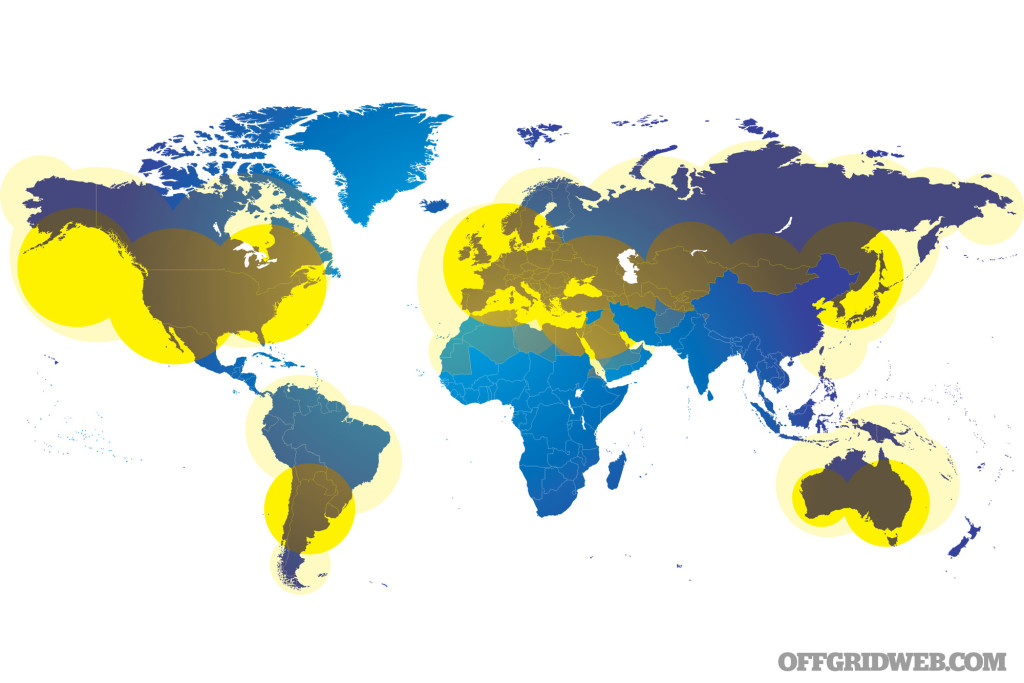

Consider other devices, such as walkie-talkies, which are good for a few blocks within city limits. GMRS-compatible radios have a greater range. CB radios and ham radios have the greatest range. I recommend ham radios. However, note that they require a license and people can listen to your conversations. Now you understand why we speak in code. (For more on ham radios, see: “Comms Are Key” from Issue 1.)

Other signaling options include lights, mirrors, light sticks, reflective markers, trail signs, and so on.

Security

Security in a bug-out scenario is broad, to say the least. Depending on the threat or the event, people could be hostile. It goes without saying that you should avoid conflict at all costs. That means being as stealthy as possible. This requires a skillset comprised of camouflage and movement. Camouflage is the ability to manipulate yourself within the environment to disappear. This is sometimes referred to as becoming a Gray Man or “going gray,” especially in the context of urban survival. It’s not the same as going to Wal-Mart or Kmart and buying some mossy oak-print clothing.

Ensuring your security is really dependent on the circumstances. If you can’t maintain ninja mode, you’ll need to consider self-defense tools. Obviously, firearms are ideal for both security and hunting. (For more on firearms, see: “Defensive Armament” from Issue 1.) There are also knives, axes, bows, and pepper spray — whether it is regular pepper spray, bear pepper spray, or a homemade concoction.

Don’t forget about the importance of verbal skills. You may be able to entirely avoid some conflicts through careful use of body language, a friendly tone, or more advanced social engineering techniques. Even if these don’t work as planned, they may give you an opportunity to escape or counterattack.

For long-term planning, consider joining a martial arts or combatives school, instead of a gym. I don’t mean some cookie-cutter romper-room or a McDojo, but rather a credible studio that teaches an authentic fighting system. Because you need to stay fit anyway (see “The Preplanning” section), you might as well train to be a badass at the same time.

Are You Ready?

It’s up to you to make this an effective SHTF plan. Start by talking your friends, family, and coworkers. If the current state of affairs concerns you, then more than likely it concerns people around you, too. Get together and make a plan based on what’s discussed in this article. You can accomplish a great deal with more people rather than less. Take a few classes and workshops, and get dirty. The journey to being prepared does not have to be long, daunting, or arduous. Make it fun; make it a game. But, practice for real.

About the Author

Shane Hobel, also known as White Feather, is the founder of Mountain Scout Survival School, based in Hudson Valley, New York. He holds various certifications, including Wilderness First Responder, CPR, and first aid, and he is a licensed guide by NY State Department of Environmental Conservation. Shane is also a certified instructor for the American Red Cross for water safety programs. Shane is a member of Tom Brown, Jr.’s elite Tracker Search and Forensic Investigation Team, which is dispatched whenever called upon to track and find lost children, hunters who became disoriented in the woods, or fugitives.