RECOIL OFFGRID Survival Could It Happen Here? Civil War Survivors Recount Lessons Learned

Over my years as a war reporter and war crimes investigator, I am often left in awe of the individuals I meet who have survived the most unfathomable things humans do to each other. I’ve sat with people who’ve had their body parts surgically removed by aggressors, women who have been raped until they can no longer move, and children whose tiny bones have been cracked and crushed without mercy.

But for those who survive, the silver lining that shines through them is as miraculous as it is tragic. I’ve often been struck by how these ordinary people, with no formal training or skills, are forced to become extraordinary at the drop of a hat — or a bomb. The resilience to withstand the pain (both physical and psychological), to push through the darkness, and to find the thread of hope in the bundle of misery has left me both perplexed and inspired.

In documenting the lives of a few of these individuals, I hope to shine a light on just how strong the human mind can be when it comes to holding on. I hope to illuminate our ability to prepare for and push through a crisis as it dawns. And above all, I hope to instill what it means to rise above being a victim and into the terrain of survivor, and to seek inner peace long after the torment and war has subsided.

One moment, Samer Scher was one of the multitude of passionate political college students flooding the wide and dusty streets of Modamiyeh, Syria, chanting for free and fair and elections. The next moment, gunfire from forces loyal to the Bashar al-Assad regime ripped through the open air and those he knew and loved fell to the ground.

As panic and lawlessness erupted in the cool spring afternoon, just like that, Samer knew that their peaceful revolution had fallen down the rabbit hole of a violent war — a war from which he and his country would never return.

Above: Samer Scher

Above: Samer Scher

“All we wanted was a future. Back then, if you didn’t have a link to the regime, you couldn’t get a good job; you had no future,” Scher, now 29, lamented from the safety of his small home on the outskirts of Berlin, Germany. “Animals had a better life than we did. We did not just want to receive decisions. We wanted to be part of the decision-making process.”

But from that very first barrage of bullets on the first day of their peaceful protests, the bloodshed and distrust only deepened. At any moment, anyone suspected of being part of the cadre opposing the Damascus overlords could be ripped from their homes and never seen again. Scores would be thrown into jails in the bowels of the earth, where they were subject to rape and torture. Many would be burned and blown apart, as bombs slammed into their bedrooms while they slept.

Samer, who was working as a volunteer medic at a local clinic, anxiously accepted that it was only a matter of time before the brutal enforcers came for him too. He had already seen bullets wedged into the eyes of screaming children and shrapnel searing the flesh of babies as they breathed their last breaths. He was left with the memory of a quiet conversation with a close friend, only to see that very friend shredded into pieces the very next day as a result of a shell slicing his body.

After three terrifying days of heavy fighting on the edge of his besieged hometown between the Free Syrian Army (FSA) rebels and Assad’s Army — a conscripted military — Assad’s forces breached the blockade and stormed in. It was August 22, 2012.

Above: A Syrian National Army tank near the combat zone in Damascus, September 2013.

Above: A Syrian National Army tank near the combat zone in Damascus, September 2013.

“I stayed in my home; there was nowhere to go,” Samer, who speaks softly with glazed eyes, continued. “It was a matter of chance — maybe the regime would come for your home, or maybe they would go for the home next door.”

Yet after nights of sleeplessness, Samer’s fogged eyes made out the shadows of soldiers peeking through the holes of his thin walls. Then, the soundtrack: gunshots cracking, footsteps, and the sounds of his front door crashing to the ground. He felt boots pelting against his limp body, splintering his bloody mouth, and then the chilling threats that they were going to shoot him.

“They were humiliating me, calling me a dog, a terrorist, insulting my family. Every one of those men — about 25 of them — were all taking a hit,” Samer said as if sifting through a graveyard of memories. “It was an unimaginable fear; I thought they would arrest me and take me to an intelligence branch.”

First, the soldiers carted Samer around the apartment building like a human shield — holding him up in case anyone opened fire as they knocked down a door. At one point, they propelled him into a bathroom, and when he turned around, he was staring down the barrel of an AK-47 at close range.

“I begged them to spare my soul, that I was just a college student,” Samer recalled.

But a bullet catapulted through his rib, another into the bottom of his arm, then another cleaved below his shoulder. Samer said the only pain he felt was the pain of fear. Facedown in a pool of crimson, he counted three more bullets entering his body and a seventh shattering the wall right by his head. He remained motionless for what felt like an eternity until the laughter and chimes of “he’s dead” faded out.

Above: Rebels in the fight against ISIS and the Syrian regime. Photo courtesy Rojava Information Center.

Above: Rebels in the fight against ISIS and the Syrian regime. Photo courtesy Rojava Information Center.

Samer managed to drag himself down a flight of crooked stairs and phone a friend for help. However, his miraculous tale of survival would only become dizzying as the war intensified into chemical attacks and mortar showers — until one day in 2015. He was given passage to flee into neighboring Turkey, an opportunity he felt would be his last chance at life. From there, he boarded a rickety boat to Greece and then moved through to Germany. Today, he’s trying to move on with life and studies, yet not leave behind the Syrian war that protracts into its eleventh year.

“I don’t know why I survived. I would say it is God’s will. I ask myself why me, and still, I have no answer,” Samer said.

Physically, he’s no longer able to lift his right arm. Psychologically, Samer is awash with an unrelenting desire to keep fighting for his country — this time with his voice.

“I’m going to run for parliament in Germany,” he noted, his strained face thawing into a wistful smile. “That’s the best I can do to protect my future family.”

Jennifer Zeng’s crumble into suffocating oppression under the fist of China’s Communist Party (CCP) was beleaguered from the beginning. She entered the world in the Sichuan province in 1966, the year that the Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution — the great sociopolitical purge to cement communism — began.

Since her father was part of a secret “intellectual” crowd, he was always on the oust of Beijing’s militant leadership and subsequently ostracized. This meant that Jennifer was born in a clinic where her parents couldn’t afford to pay bribes for the best medical care. As a result, a blood transfusion gone wrong in her first few days of life left her with hepatitis C.

Ironically, it was that liver-ravishing condition that would, decades later, save her life. Her early life was plagued with mandatory “re-education” classes on the fringes of an isolated town, forcibly separated from her mother. Any minor change her father wanted to make, from work to moving to a different house, couldn’t be done without government approval.

“My childhood was very lonely. And because my family was looked down on by society, I was discriminated against — even the school would not let me play with other kids,” she said wistfully, her eyes darting off into another world. “We had to be very careful, and life was very hard.”

She didn’t know then just how much harder it would become.

It wasn’t until 1997, when Jennifer was in her early 30s and working in Beijing, that she stumbled upon furtively distributed books about an emerging spiritual adherence called Falun Gong. It was a belief system outside the purview of the authoritarian leadership. For two years, she’d meet other practitioners to pray and meditate under the shroud of secrecy.

Then, in the summer of 1999 — after hearing that other Falun Gong believers were being apprehended — Jennifer went to the State Appeals Office to plead their case. But authorities abruptly rounded her up too. She was stuffed into a detention center for 48 hours, and her name etched into a black book that would haunt her for many more years.

Inside the labor camps, time was double-edged. The seconds of torture were elastic — stretching on, with one always waiting for the tenuous band to snap. But the longer she could keep propelling through, the closer she felt to making it to the other side.

Jennifer was arrested for the second time in February 2000. This time, she was dragged out from her workplace — an investment consultant company — and viciously interrogated at a labor camp in China’s Da Xing County. Before officials drew her blood, she informed them that she had hepatitis C. While she was left to starve over the coming weeks, many around her — including her cellmate — dropped dead from forced feeding.

That’s when Jennifer realized that the organs of Falun Gong practitioners were being nightmarishly harvested to meet the demands of a government-run for-profit organ industry. She was eventually released from this torturous captivity, but not for long. That April, heavy-handed police officers plucked Jennifer from her sleep just after the witching hour with no explanation.

It was only days later that she learned authorities had intercepted an email she had written to her parents, explaining her zest for the Falun Gong faith despite it being outlawed by the CCP. While some criticize it as being something of a cult, Jennifer maintains that her Falun Gong practice is rooted in meditation and compassion.

But for weeks that swelled into months, Jennifer’s life in yet another labor camp would fall to the hands of that faith.

“Every day was a struggle between life and death. Most days, we were forced to squat for 16 hours, with our hands behind our heads like dogs. Police would immediately apply electric batons to anyone who fainted to wake them up,” she said. “On the other days, we were made to stand motionless in our cell for those 16 hours.”

When Jennifer refused to renounce her religion as “evil,” prison guards lugged her into a filthy courtyard and whipped her raw with electric rods until she lost consciousness. Yet, the worst pain wasn’t physical. It was watching once bright-eyed humans descend behind the curtain of madness.

“At night, you would hear the screams of those being tortured. Sometimes, I felt that I would collapse and lose my sanity. That was the most terrible fear for me,” Jennifer continued. “You could see the moment when someone would lose their sanity — when they couldn’t handle the mental torture anymore. Their eyes changed. Their minds went somewhere else.”

As soon as she was set free months later, Jennifer knew that China was no longer home. The only way she would survive was to be somewhere safe enough to tell the world what was happening to the Falun Gong practitioners. She had to make the excruciating decision to leave her 10-year-old daughter and husband behind and flee first to Australia as an asylum seeker in 2001. Years later, Jennifer relocated to the United States, where she has continued her advocacy as an independent writer.

For now, watching China continue to assault minorities from the Muslim Uighurs to the Buddhist Tibetans from afar is like observing a slow-burning home from behind a frosted glass window. The nightmares haven’t stopped, but Jennifer leans on meditation and deep breathing until the fear fades away. It’s those pillars of benevolence toward all forms of life that pull her through the darkest of days.

“That is the greatest gift, the best skill that I can give myself,” she says with a smile.

For M Tu Aung, 46, life has always existed as an endless cycle of running — running from danger, running into the unknown, running to lands far away and then running in circles in the hopes someone might hear his cries and prayers.

Above: M Tu Aung outside the Chinese Embassy in DC in April 2021, protesting the military takeover in Burma. Above: Photo by Hollie McKay

Above: M Tu Aung outside the Chinese Embassy in DC in April 2021, protesting the military takeover in Burma. Above: Photo by Hollie McKay

“We had to run whenever the military would come in. They would try to kill all the people, they would set fire to the villages and burn down the churches,” recalled Aung. He was raised in the predominantly Christian Kachin State of Burma — also known by its 1989 regime re-title Myanmar — during a time of socialist military governance. “If you could not run, if you were not fast enough, you would be taken by the Burmese Army. Many times, people were killed, and yet we could not stop to bury the bodies — if they caught you, they would kill you. Some of my family members who were running beside me were caught.”

Burma has been burned alive by endless conflicts and persecution since the British handed the country back its independence in 1948. Given the endless wars, Aung never knew his biological parents and was adopted as an infant. He also never knew a life not beset by killing fields.

“They (Armed Forces) wanted all the property for themselves. We always had to run and leave our village and property behind. Everything would be ruined; the Army has no regard for human life,” he continued. “Every day, we lived in fear. We worried, day and night, they would come.”

Above: Photo by Hollie McKay

Above: Photo by Hollie McKay

Even if there were peaceful moments inside the threads of the jungle, idyllic in their stillness, they were beset by biting anxiety. There were no warning signs, Aung said, just a crackle of gunfire and howls of panic whenever the troops would force their way in.

“What I remember most about my childhood is how the soldiers would just come into our villages and take anything they wanted. And they would take the people — sometimes 15 or 16 years old,” he whispered.

Like many from the region, the more painful the topic, the more the survivor laughs — an uncomfortable defense mechanism to mask the invisible wounds nested into memory.

“The Burmese Army would kill and torture — and they would rape,” he said slowly. “I remembered the faces of the young girls and women who they would take away to rape. We didn’t know exactly where they were taking them, but the ladies — most of them — never came back.”

Aung believes he only survived a tumultuous upbringing because his adoptive parents moved him to Rakhine State when he was 15, a state that — back then — was somewhat less butchered.

A decade ago, Aung was granted asylum in the United States with the wild hope for a better life. He studied for an MBA and opened a small business in Maryland. He fell in love with another refugee from Burma, married and had three children, and is heavily involved in the local community of Baptists churches.

Above: Photo by Hollie McKay

Above: Photo by Hollie McKay

But it’s the place he left behind that occupies his mind during most waking hours. He exhibits a dogged devotion in reaching out to the powers of Washington as an active leader in the Nationalities Alliance of Burma, a network of ethnic nationalities organizations based in the United States.

“It has always been about a ‘burmainization’ of the country, of everyone else not in the military circle being treated as second class,” Aung lamented. “The Burmese military wants us out to protect themselves. It is why they are killing protestors and civilians every day.”

Some of Aung’s frustrations have stemmed from the notion that little has been conveyed to the public about the suffering of Christians in Burma. Most of the world is painfully aware of the persecution that the Muslim Rohingyas have endured in recent years in the Rakhine State he settled in as a teen, with many forced to flee into bordering Bangladesh. Aung said Christians have also been slaughtered and have had their houses of worship razed into nothingness, but have been “weak” at conveying the situation on social media.

Above: Photo by Hollie McKay

Above: Photo by Hollie McKay

“The ethnic cleansing has been happening since long before that of the Rohingya people,” Aung stressed.

Watching his homeland once again be dipped in chaos and blood following the coup in February 2021, in which the military wrestled power back from the first civilian government, Aung feels the urge to keep running. He’s calling for the international community to step in and support a transitional government in that illustrious chase for a free and fair election, calling for the people of Burma to decide their fate.

And despite 10 years in the United States, Aung clings to a life of trauma that reminds him he may never truly know what it is to be safe and secure. He leads a minimalist life with no stockpiling — when all one knows is to run, less is more — and his body is engulfed by chills at the mere sight of any uniformed soldier.

“Even here in the U.S., I just don’t want to see a soldier. It scares me,” he notes with a nervous giggle. “All that is really left, all we can do, is pray for protection. That helps us a lot.”

Then, there’s the case of Mohammed Soltan, 33, in which the torture of the unknown still visits him at night. His father “disappeared” months ago into the depths of an Egyptian prison. Last year, intelligence officials informed him that prison guards broke his dad’s jaw and his teeth, yelling that it was his son’s “treachery” for which he must pay the price.

Yet Mohammed, a former Egyptian political prisoner himself, refuses to be silenced. He also refuses to wear the weight of guilt that his dad is suffering because of his vocal activism against the military leadership in Cairo.

“I won’t take that on,” Mohammed said defiantly. “That is on them.”

Above: Mohamed Soltan poses for a photo at his sister's home in Fairfax, Va., on Friday, August 21, 2015. Soltan spent over two years in jail in Egypt including a year on hunger strike. (Photo by Zach Gibson / The New York Times)

Above: Mohamed Soltan poses for a photo at his sister's home in Fairfax, Va., on Friday, August 21, 2015. Soltan spent over two years in jail in Egypt including a year on hunger strike. (Photo by Zach Gibson / The New York Times)

His father and five cousins are being housed in the recesses of the very same underground prison Mohammed was thrown into in August 2013.

But his journey of political activism was one of default. He grew up in what he describes as simple, rural American life in the Midwest — white picket fences, sprinkler summers, and frosty winters. But when the 2011 Arab Spring erupted in Egypt, the place of his heritage, Mohammed wanted to experience what he hoped would be real change in the region.

“I remember watching the protests in my history class at Ohio State University and just knowing that I needed to be there,” Mohammed recollects. “I left the airport and went straight to Tahir Square. It was February 11, and longtime President Hosni Mubarak stepped down. It felt like the whole trajectory of my life had changed. It seemed like a dream. The young people of Egypt had spoken, and we had taken our country back.”

Only his dream of freedom fast descended into a nightmare. After completing his studies in the U.S., Mohammed moved with his father to Egypt in March 2013 to build a life working with the newly elected Mohamed Morsi leadership. However, just a few months later, Egyptians poured into the streets to showcase their displeasure at Morsi, setting up a succession of clashes.

After a few days of demonstrations, the country’s former defense minister Gen. Abdel Fattah el-Sisi oversaw a controversial takeover of power. That part of it had been relatively sudden, Mohammed said. There had been no warning signs to get out early. It seemed that the transition would be one decided by the people … until it was not.

“I was very scared that the military was coming back and interrupting a democratic space. We had hoped there might be a referendum,” Mohammed continued.

The summer flared with the heat of protests and confusion swarming the streets, both in support and in objection to the Army’s government overhaul. Mohammed had been live-tweeting about the chaos erupting around him at Rabaa Square when a bullet zipped past his head. But before he could breathe relief at the near miss, another bullet tore through his arm.

While attempting to tend to his wound without access to proper medical care, Egyptian authorities burst through his home. They were initially looking for his dad, who wasn’t there. So instead, Mohammed was taken away in what would amount to months of beatings, cigarette burns melting his unwashed flesh, the cracks of his bones breaking and the gut-wrenching feeling of his left shoulder dislocating from his deltoid muscle.

He remembers nails being pressed into his wasting frame during regular torture sessions, and the way his angst would spew into anger every time authorities attempted to force-feed him. Each time, he’d immediately tear the IV drip out of his weakening body.

While behind bars, Mohammed launched a hunger strike that stretched from months into more than a year.

As an American, Mohammed had a robust government on his side that was able to demand his release. After 22 months — including 489 days on a hunger strike, wrapped in despair — he was set free into the sunshine on May 31, 2015. But as any torture survivor will tell you, there’s never really a place one can call home. After that, authorities retaliated by arresting five of his cousins and his father.

Along with the deep pangs of knowing that his dad is still out there in the darkness of the dungeons, alone and in misery, Mohammed still frantically jumps at the sound of keys shaking or doors slamming — sounds that signified the guards coming into his cell for another round of caustic games. His stomach violently rejects heavy meals, and being alone comes with a bundle of distressing solitary confinement reminders.

“I have to keep speaking to myself,” he said. “It’s how I can assure myself that I am still alive.”

The work is far from over. Mohammed’s life now is stuffed with pushing for the release of other political prisoners around the planet, in what he characterizes as “paying it forward.”

“I didn’t think that I ever would get out of prison, and I know that any of us can die at any minute,” he conjectured. “But I have this second lease on my life to fight for others, and that’s the lens through which I view everything. That is why I will be forever grateful.”

The upheaval of one’s life isn’t always at the behest of one’s own government. Sometimes, the lack of stability and internal corruption of leadership lays the groundwork for external influences to swoop in and unleash havoc on an innocent populace.

That’s an eerie narrative that Victoria Nyanjura knows all too well. She was just 14 years old when insurgents, under the canopy of Joseph Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), stole her and some 138 other girls from their Catholic boarding school in the Kole district of northern Uganda. These events unfolded in the dead of the night on October 9, 1996.

There had been rumblings weeks earlier that the rebel outfit might invade, yet nothing had come of it. When it happened, it came as a scalding shock — grenades detonated in the dark, wild-eyed fighters rattled the gates until they broke, and then there were the screams. The piercing screams that Victoria will never forget as she glanced up into an abnormally bright sky.

“I tried to hide under the bed, but they found me and took me. I didn’t know what was happening,” she observed, in a small yet stern voice that signified her propensity to push through. “I did not know whether they would let me live or die. But that was the start of all my misery.”

Kony’s name and his trail of terror didn’t become apparent to most Americans until 2012, when the abuses of his self-styled militias were brought to light in a viral video focused on recruiting child soldiers. But for eight years, many moons earlier, it was all Victoria lived and breathed. Thirty of the 139 girls were handpicked and dragged away to be bush wives to the insurgents. Nyanjura was plucked and tied up with banana leaves so she couldn’t run, and immediately she knew with a sinking feeling her life would never be the same.

“Every night, they are having their way with you, and there is nothing you can do. Everything about captivity is about survival. You either survive, or you perish; there is no in-between,” Victoria said. “Often, you would see someone fall to the ground and think they must be resting, but when you get closer, you realize they are gone.”

Above: Victoria Nyanjura

Above: Victoria Nyanjura

Her years of survival were pockmarked by sucking raindrops and dew for water, secretly gathering wild fruits and hoping that they would not be poisonous, sitting in the sunshine with a body so bruised and swollen, and sobbing to live. Other times, she was sobbing to die.

Victoria’s “husband” was eventually killed in the fighting against Ugandan forces, and for years more, she held her two small children — a daughter and a son — tight and quietly prayed and wept for the will to keep forging ahead. The LRA distinguished itself by slicing off victims’ limbs, lips, and noses — a symbol to instill terror in communities and scar survivors for life, making them forever dependent on others to get by.

“There were times that I begged to God to let me die, that things would be better if I were not there,” Victoria confessed. “I begged if I died; I wanted my children to die too. I wanted us all to perish together.”

One day, Victoria snapped. By that point, she was 22 years old, and much of her life had existed in the confines of captivity, on the tightrope of death and destruction, in the shadow of the grossest miscarriage of justice. She could not take it for one moment longer. With that, Victoria swept up her two children and set off a daring escape that entailed weeks of weaving through a boundless maze of jungle and gray sheets of tropical rain, over hills and into valleys of the dead — praying that she wouldn’t be shot at or re-captured, or step on a land mine embedded in the muddy tracks.

Eventually, Victoria made it to a displacement camp, where she was forced to confront the stigma of surviving sexual violence and shielding her young from the origins of their conception. Now 39, Victoria recently completed a master’s degree in global affairs, focusing on international peace studies, at the University of Notre Dame.

Yet last year, she chose to return to Uganda not only to start explaining to her now-grown children what had happened, but to support other women and survivors of traumas with her own non-governmental organization. Victoria admitted that she struggles to have any sense of a typical romantic relationship and accepts that the healing process is jagged with steps forward and steps back.

But her voice is resilient, with a fierce protectiveness of her children. She will never let happen to them what happened to her.

“In captivity, I called my daughter Hope. There was no other name I could give her because I just had to have hope that God would get us home,” Victoria added. “For anyone in a tough situation, I would say never give up on life. Never give in, never give up. You have to have hope for a better tomorrow.”

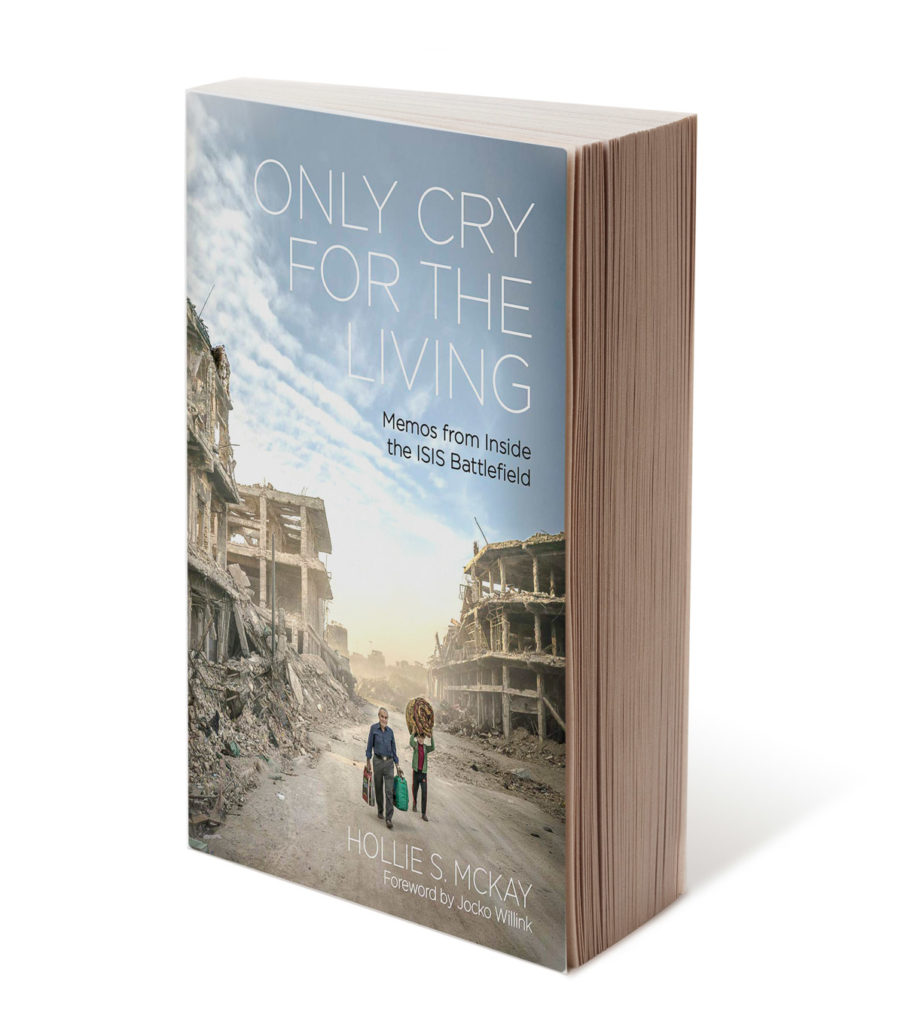

Memos from Inside the ISIS Battlefield

Get your copy of Hollie McKay’s latest book by going to gundigeststore.com/living.

STAY SAFE: Download a Free copy of the OFFGRID Outbreak Issue

STAY SAFE: Download a Free copy of the OFFGRID Outbreak Issue

No Comments