Photos by Tammy Cobb

I don’t know anyone who doesn’t end up with a stack or two of newspapers or advertisements in their recycling bins each week. Even if you don’t subscribe to the daily paper in your area, odds are there’s at least one free newspaper that is delivered regularly along with a seemingly endless supply of ads, coupons, and classifieds. Some folks call this the local fish wrap. The point is just about everyone has unwanted printed matter lying around.

You could, and should, recycle what you don’t need. But in here we’re presenting some ways you can repurpose it around the house, focusing on survival or self-reliance–related purposes.

Before we get into the projects though, let’s talk for a moment about newspaper. Not all newspaper is created alike. There’s newsprint and there’s glossy paper. The glossy paper is what is typically used for advertising. Ya know, the shiny, full-color ads that are designed to draw you into the stores so you’ll buy more junk you don’t need or can’t afford. Toss that stuff right into the recycling bin. We have no use for it here. What you want is the actual newsprint.

If for some unknowable reason you’re that odd person who receives absolutely no newspapers at home, but you still want to try out some of these projects, you have a couple of options. You could ask a friend, relative, or neighbor to save some paper for you, of course. Or, you could head down to the local newspaper office and ask about “end rolls.” These are rolls of clean newsprint that only have a bit of paper left. Trust me, each end roll will have plenty for our purposes here. Some newspapers give them out for free, others might charge a small fee.

Incidentally, if you have kids or grandkids, roll out enough clean newsprint for them to lie on, then trace around their entire body and head. They’ll have a blast using crayons to draw life-size versions of themselves. It also makes for great wrapping paper for the holidays, just dress it up with some markers or stickers.

Plant Pot

This is a great project for the kids to do on those days when they complain about being bored. It requires newspaper, a bottle, and soil. There is a product on the market called a Pot Maker that works outstandingly well for this project. I highly recommend it. The mechanics of the project are the same whether you use the Pot Maker or a bottle. A wine bottle works great, but if that’s not available, any bottle of similar size will work. The ideal bottle will have a concaved bottom.

Cut the newspaper into strips about 6 inches wide. The length will depend upon the size of your bottle. The strip will need to wrap completely around the bottle twice.

Wrap the strip around the Pot Maker twice. Fold that loose newspaper in and crimp the fold around the bottom edge of the dowel. Slide the pot from the dowel and fill with soil. The soil helps the pot keep its shape so be sure to fill the pots even if you don’t plan on using them right away.

Once the seedlings are ready to be transplanted outside, you don’t have to remove the pot. Just dig the hole and drop the whole thing in. The newspaper will decompose just fine.

A plant pot made of newspaper is cheap and easy to make. Plus, you don’t need to remove or replace it later...

Seed Tape

If you’ve ever planted carrots or lettuce, you know just how frustrating it can be to deal with those itty-bitty tiny seeds. We always just end up sprinkling the entire seed packet into a trench, resigning ourselves to the knowledge that we’ll just be thinning the seedlings once they sprout and thus wasting quite a bit of seed. But, with a little effort ahead of time, you can use newspaper to cut down on the amount of seed you end up using in a season, thus extending your supply. Plus, you won’t be doing nearly as much thinning as the plants grow.

Start by cutting the newspaper into strips about 1 inch wide. Length is up to you, but I find it easiest to work with strips no more than 18 inches long. Next, make a glue using 2 tablespoons flour and 1 tablespoon water. The mixture should be fairly thick.

Read the instructions on the seed packet to find out the recommended plant spacing. If you don’t have the original seed packet, do some research online. For our purposes, we’ll say it’s 1 inch. Lay out your newspaper strip and use a ruler and pencil to mark the seed spacing. Leave room on one end of the strip so you can label the strip.

Dip the tip of a toothpick into your glue, then use it to pick up one seed. One at a time, smear the glue and seeds on the strip at the spaced marks. Let the strip sit out until the glue has fully dried. Use a marker to label each strip with the type of seed. Roll up or fold the strips to store until needed.

To use, simply dig a trench in your garden to the appropriate depth, lay in your seed tape, and cover with soil. Water thoroughly, and you’re done!

Garden Bed

If you have the time to wait, newspaper can be a tremendous asset in creating a new garden bed. Put down a few layers of newspaper over the entire surface of the planned garden bed, weighing the paper down with rocks or logs. Let this sit for a season and all of the grass and weeds will die off. This makes it much easier to till up the ground and get things ready for planting.

Fire-Starter

Having a reliable way to get a fire going can be critical to survival. Sure, there are all sorts of fire-starters on the market today and most of them work rather well. However, if you have a stack of newspaper and a few old candles, you can make fire-starters that work just as well as some and even better than most.

Roll a few sheets of newspaper together so the end result is about 1 inch thick. Use jute twine or some other type of cordage to tie the roll together at several points. Cut the roll into sections, each a couple of inches long. Be sure you have at least one loop of twine around each of these sections.

Submerge each of these sections into melted wax, and then set out to dry for a few minutes. To use, simply light the jute twine as though it were a fuse. You could also scrape a bit of wax away from a corner and light the paper directly. These fire-starters burn a good long time.

Toilet Paper

It isn’t nearly as soft as Charmin, but it’ll do in a pinch — and far better than trying to decide if those leaves look like poison ivy or not. You can make the experience a little more tolerable by repeatedly crumpling up the paper so it softens the fibers a bit.

Fire Log

As should be obvious to just about everyone, newspaper burns quite well. It is, after all, just wood pulp. There are gadgets and gizmos out there that will turn shredded paper into bricks or logs for burning. That’s all well and good, but the method I’m going to describe requires nothing more than a small tub of water and a dowel.

Fill a basin or tub with warm water and just a squirt of dish soap. Separate the newspaper into sheets, then pile them in the water and let them soak for an hour or so. Drain the water and lay the sheets out in sections, overlapping them a bit. Begin at one end with the dowel and roll it along, wrapping the newspaper around the dowel. Keep adding paper until the log is about 4 inches thick or so. Slide out the dowel and your log is complete.

Lay the logs out to dry, which can take a few days to a few weeks depending on climate conditions. I wouldn’t suggest using these exclusively in your fireplace or wood stove, but they can help extend your supply of firewood by using them here and there. They won’t light right off a match, but will catch just fine off of some kindling.

These will produce a bit more ash than regular logs, but the benefit of increased fuel for the wood stove with little impact on your wallet will probably outweigh the inconvenience of one more bucket of ash to empty each week.

Improvised Weapon

Newspapers for self-defense? What are you going to do, paper cut them to death? OK, newspapers wouldn’t be my first choice for a weapon, nor my second, third, or even fourth. But, as a last resort, it’ll do the job. How?

Take about five sheets of newspaper and roll them up as tightly as you can. The resulting baton will be strong enough to be used defensively against certain attacks. Offensively, you could swing it like a small club, but it’s way stronger at the ends. Better to thrust the baton’s tip into a bad guy’s eyes, throat, or groin, or use the butt-end to hammer on vulnerable areas. Either way, your newspaper baton will certainly get an assailant’s attention.

Sort of a variation on this theme is the Millwall brick. Roll the newspaper as before, then fold it in half. That’s it, you’re done. The striking surface is the fold. The more newspaper used, the harder and heavier the brick will turn out. You can make the weapon a little more lethal by adding a few nails to the business end of the brick.

This simple tool is the namesake of London’s Millwall Football Club, whose fans were notorious for hooliganism. In the 1960s and 1970s, they allegedly used Millwall bricks to raise hell because pretty much every other improvised weapon had been outlawed. Where there’s a will there’s a way, right?

As a last resort, a rolled-up newspaper (and its Millwall brick variation) can be a decent improvised weapon when...

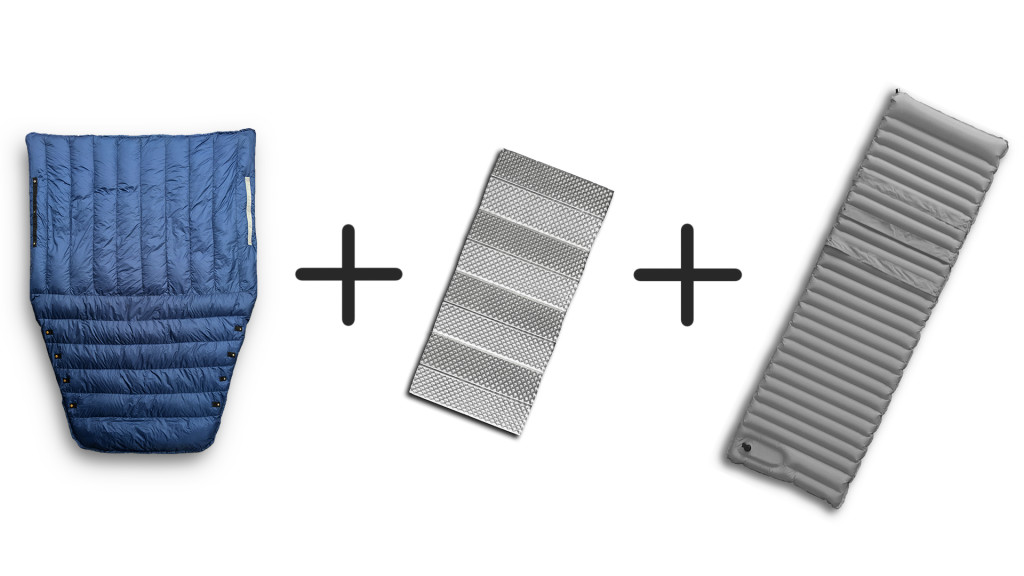

Insulation

You’ve no doubt seen the cliché in the movies of the homeless dude stuffing newspaper into his coat or pants, right? Guess what, it really does work to keep you warm. Newspaper, just like most of the puffy coat fillers you find on the market today, add dead air space between you and the outside chill. Your body heat warms that dead air, which is what keeps you from shivering. You may feel like the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man, but at least you’ll be warm.

Newspaper also works as an insulating material around the home. When you find a cold draft coming in from the side of a window or door, stuff the crack with newspaper. It might not look all that awesome, but it works. Keeping out the cold outside air can be very important if your only source of heat is the fireplace during a power outage.

If frozen pipes are a concern, wrap them with newspaper. You can also run the taps at a light trickle to help keep things from turning to ice.

Boot Dryer

Wet footwear can be a serious issue and could lead to frostbite or worse in bad conditions. You can use newspaper to dry out your boots and shoes. Stuff loose crumples of paper into the boot until you can’t fit any more inside and let it sit overnight. If the boots are really soaked, replace the paper with dry crumples after a couple of hours, then let it go until morning.

Conclusion

Even though they rarely carry good news these days, there is little in life more ubiquitous than newspapers — even in this Digital Age. Newspapers are so common we often overlook it as a useful resource. The true survivalist, though, tries to utilize everything and anything to achieve his or her goals. The survival uses of newspapers don’t end here, as their limit is really just your imagination.

About the Author

Jim Cobb is a recognized authority on disaster preparedness. He has studied, practiced, and taught survival strategies for about 30 years. Today, he resides in the upper Midwest with his beautiful and patient wife and their three adolescent weapons of mass destruction. His books include Prepper’s Home Defense, Countdown to Preparedness, and Prepper’s Long-Term Survival Guide. Jim’s primary home online is www.SurvivalWeekly.com. He is also active on Facebook at www.facebook.com/jimcobbsurvival. Jim offers a consulting service as well as educational opportunities at www.DisasterPrepConsultants.com.

More From Issue 13

Don’t miss essential survival insights—sign up for Recoil Offgrid’s free newsletter today.

Read articles from the next issue of Recoil Offgrid: Issue 14

Read articles from the previous issue of Recoil Offgrid: Issue 12

Editor’s Note: This article has been modified from its original print version for the web.