This article originally appeared in Issue 7 of our magazine.

There are a few Latin phrases that speak perfectly to the prepping lifestyle. Probably the most applicable is “Praemonitus praemunitus,” which transliterates roughly to “forewarned is forearmed.” Essentially, it means that having advanced warning gives you a tactical advantage. The better your situational awareness, the more informed your decisions can be and the more likely you are to maintain your safety and security.

In a crisis event, using unconventional methods to increase your situational awareness and information-gathering abilities may become a necessity. What was that explosion? Was it a fuel tanker blast or a terrorist attack? Is the smoke toxic and which way is it blowing? How is it affecting my prearranged evacuation routes? Sometimes, those key questions can be answered quickly by Google or your local TV news station. But what if the grid’s down or you can’t get a mobile phone connection? This is where the use of a personal unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) comes into play. We’re not talking about the big military drones that look like scaled-down fighter jets seeing hard use in the Middle East and around the world right now. Rather, we mean the thriving market of smaller drones that are more easily set up in any off-grid scenario.

We’re not advocating an overreliance on gadgetry when SHTF. After all, most of the content you find in OFFGRID centers on how to survive and thrive based on your skills and ability to adapt, not on the price tag of your kit. However, when it comes to getting a tactical advantage over a marauding horde who failed to prepare, we’re all in. And you’ll be surprised to find that some drones aren’t that expensive, don’t require much training, and in a survival situation can perform amazing feats that you couldn’t possibly do yourself.

Drone Utility

EdStock/istockphoto.com

Above: Coming in all shapes and sizes for a variety of uses, drones can be almost as long as a fighter jet or small enough to fit in the palm of your hand. Here, a German Army soldier prepares a EMT Aladin for a reconnaissance mission.

First, let’s define what a drone is. Usually when someone says “drone,” a mental image pops up of a MQ-1B Predator or MQ-9 Reaper cruising at 20,000 feet, dropping bombs on terrorists. These models are fixed-wing aircraft with push propellers, almost the same size as fighter jets, operated remotely by Air Force pilots (who could be halfway across the world). But the personal drones we’re focusing on are almost miniature in comparison. They’re small multi-prop machines that fit into a 2-foot-square footprint, can be operated by a tech-savvy child, and never stray more than 1,000 to 1,500 feet away.

So, you might still be asking, “How does this figure into my SHTF plan?”

Well, most people’s emergency plan of action is often limited by how far you can see at any given moment. Putting a camera on a drone not only expands your vision to a bird’s eye view, it also allows you to build a defensive perimeter based on real-time reconnaissance. Without a camera-equipped drone in the air, the only way to increase your awareness is to send out a scout. That might not be a scary thing to do if your survival group is made up of former Marines, but what if your crew consists of only you, your wife, and your 10-year-old son? Do you put one of them in a potentially sticky solo situation, or do you leave them to fend for themselves at basecamp while you survey the land yourself? A tough choice either way in this scenario.

Above: Drones can be flown into caverns, over water, and into industrial complexes alike to search for help, victims, or supplies.

Your personal UAV can be also used to:

- Get “eyes” on inaccessible locations

- Monitor approaching weather

- Summon aid when in distress or stranded

- Deliver small supplies to remote areas more quickly than on foot

- Observe in real time any approaching threats from other groups

- Cover more area when searching for lost members of your group

- Reduce your wandering time by helping you quickly and accurately locate sources of water and food

You’re limited only by your creative abilities to adapt this technology to any situation.

Off-Grid Considerations

OK, so we’re now sold on the true utilitarian value of what some might consider nothing more than the latest must-have tech toy. With more onboard computers, GPS integration, and other customizations suited to your specific needs, a commercially available drone is far from a trendy toy. And with the rising popularity of these vehicles — thanks to their use in Hollywood productions and companies like Amazon researching the technology for same-day (possibly even same-hour) deliveries — personal UAVs are quickly becoming more reliable and ready-to-fly options. The buyer is no longer relegated to figuring out the engineering and science of flying a camera 400 feet overhead.

Before getting into the specifics of each component, let’s shoot the elephant that’s sitting in the corner and squelch some of the naysayers:

Concern No. 1

But drones are electronics! What if the grid goes down?

Personal UAVs run on rechargeable batteries so, yes, you’ll need a means of recharging them. Fortunately, solar-powered charging kits are readily available, and a conventional generator will do the job. Besides, you have other emergency items that require rechargeable batteries (e.g. flashlights, walkie talkies, etc.), and these are no different.

Concern No. 2

If GPS satellites are offline, how is your drone going to fly?

The Global Positioning System is only necessary for a few functions, such as auto-pilot assist and mission route planning (see below). Every personal UAV can be flown manually without the aid of GPS.

Concern No. 3

By using a drone, you’re sending up a flag, disclosing your position to bad guys.

This is only a concern if you’re in a defensive position and there’s an imminent threat. Even then, being able to get a real-time broad picture of your surroundings puts you at a far greater advantage than hunkering down waiting, not knowing the magnitude and position of the threat. However, the large majority of crises don’t involve Hurricane Katrina-level looting and pillaging. Statistically, you’re more likely to use a personal UAV to search for food, help, or a clear bug-out path.

Drone Rules

As is often the case, innovations come first — then are followed by regulations. Just like many other emerging technologies, drones have developed exponentially in the past decade, but U.S. lawmakers are slow to catch up. It’s legal for civilians to own and use drones for recreational use, but there are certain restrictions (e.g. drones can’t fly higher than 400 feet and must be kept in view of the operator). To find out more information and to stay updated on the drone rules, visit www.faa.gov and www.knowbeforeyoufly.org.

Eye in the Sky

There are three key components to a personal UAV: the motor configuration, the camera/first-person-viewing system, and the GPS autopilot.

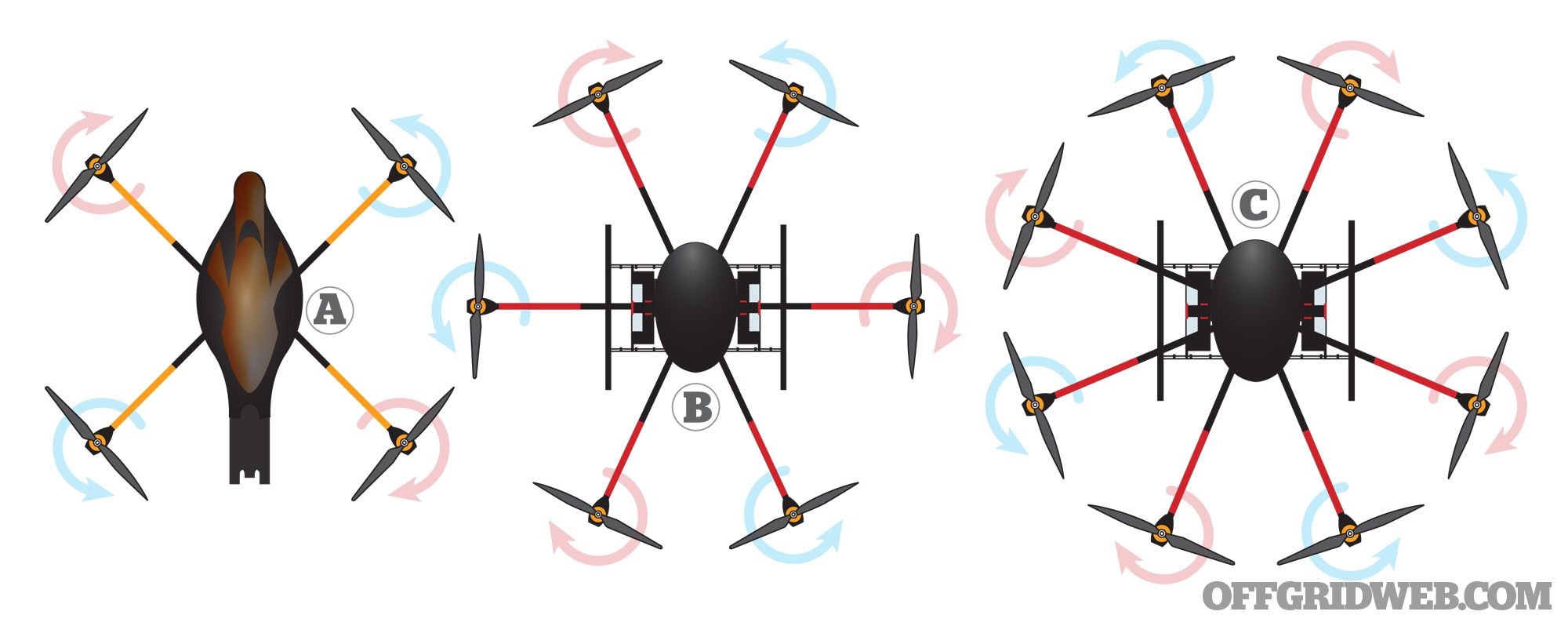

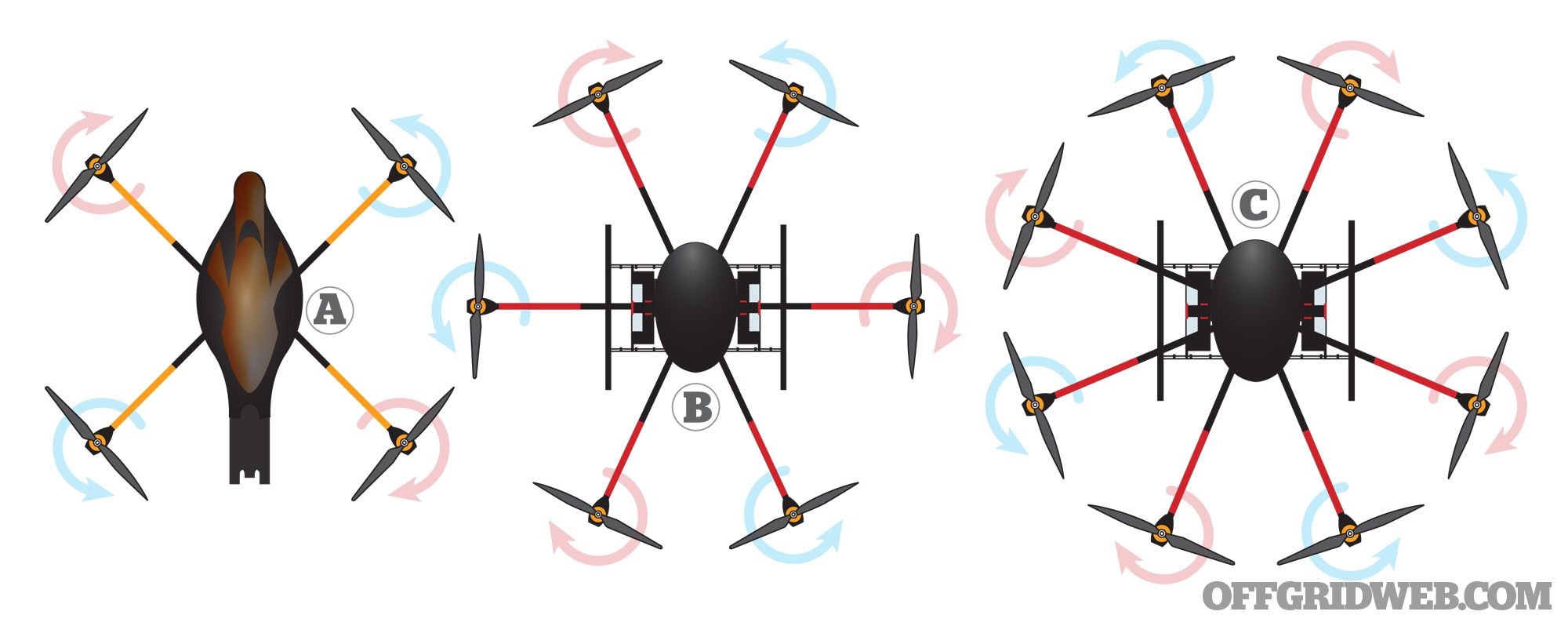

A) A quadcopter is a drone with four propellers.

B) The six-bladed drone is also known as the hexacopter.

C) Octocopters have eight propellers and are generally more stable in the air — but also weigh more and require bigger batteries.

The size and flight characteristics of the personal UAV are largely determined by number and configuration of the motors (each with a propeller). If there are four motors, it’s a “quadcopter,” six means it’s a “hexacopter,” and eight an “octocopter.” The rule of thumb is the more blades spinning, the more stable it is and the more weight it can lift. The flip side is that the aircraft will also be bigger and require a heftier battery.

Most commercial drones act as a platform for sending a camera skyward. The overwhelming king of “sky cams” is GoPro. Sure, there are other action cameras out there, but most everything in the market is set up for the GoPro. The camera is mounted to the drone via a gimbal. Without getting too technical, a gimbal keeps the camera still and absorbs any shakes or sudden changes in direction whenever the personal UAV is in motion.

Now you’re asking, “My camera is up there, and I’m down here. I don’t want to wait to download video from a card. I need real-time intel!” Luckily, there are a couple of options. GoPro has an app that lets you monitor what your camera sees. This is a short-range option, and sometimes the video is sketchy and the feed can be unreliable. Fortunately, there are many drones available with full first-person-viewing (FPV) functionality. That means you’ll see what the camera sees in real time, no delay, and in full color. Using FPV is critical in personal aerial surveillance. Unless you can have immediate visual feedback, you’re just buzzing around blind and gathering information that may be obsolete by the time your bird lands.

Air Traffic Control

These multi-copters aren’t just a hunk of plastic with a camera flying around aimlessly. These are sophisticated, but low-maintenance machines. You needn’t have any skill as a pilot to fly these babies. Each has a bevy of computers and sensors crunching out algorithms to keep you going flat and straight. Accelerometers adjust the speed of the props individually to keep your drone level in flight. If you feel like your flying is getting a little squirrely, just take your hand off the controller and the GPS system allows you to hover in one spot hands-free until the battery wears out. Still, it will behoove you to practice flying your drone and become familiar with it, lest you pilot it into a tree or building under the stress of a real-life situation.

Speaking of low batteries, most personal UAVs will return to the point of origin when the battery starts to run low. You can also recall your drone with the flip of a switch.

Drones such as this DJI Phantom 2 Vision+ pair easily with a smartphone app for mission planning and camera view.

The most useful Skynet-like feature of these machines is their ability to run a mission with no inflight input from a pilot. The autopilot works in conjunction with a smartphone or tablet. Since it’s a closed connection between the device and the drone, no cell service is required. An app that looks like an enhanced version of Google Maps calculates your current position via GPS (so the satellites have to be accessible). On the map you literally draw the area you want your personal UAV to fly in then tell it if you want it to fly along a specific route or perform a grid search, how high you want it be, and where the camera needs to be looking (all very intuitive menu-driven tasks). Once the UAV gives you the go sign, just step back, hit execute, and your personal UAV goes about its mission, leaving you hands-free so you can focus on the video feedback.

The only other thing needed is the means to power your multi-prop. Being as prepared as we know you are, you probably already have a power-replenishment plan in place for key electronics like flashlights and communication devices. Now, it’s just a matter of slipping your fly-boy into that plan, be it stocking up on the right rechargeable batteries, packing a solar-powered charger, or firing up your portable generator. Keep in mind, UAV batteries often have special connectors, but they do charge just like any other battery.

Closing Thoughts

The phrase “knowledge is power” is a cliché because it’s universally true. In this case, a drone can make you more powerful in a disaster when everyone else is powerless (figuratively and literally), scrambling around like headless chickens after the grid goes down. You could say that a bird in the air is worth two, maybe three, scouts in the bush. Even though it’s more expensive than other categories of survival gear, a personal UAV can provide priceless information and peace of mind.