Five seconds. Only five seconds had passed. But it felt like five hours as your mind slowly processed what had happened. The booming sound outside of your home, the rattling of the old single-pane windows, the screaming you heard on the street — all of it let you know that something horrible had struck.

You were just a kid when the Sept. 11 attacks happened, but it had a major impact on your childhood. Maybe today it was happening again.

Terrorism is the new Cold War. Many of us today worry when the next big ISIS or ISIS-inspired attack will occur and in what form it will take. Some of us are so concerned that we’ve taken measures to be prepared for it. But what happens when it’s time to leap from theoretical plans to a state of action? In this edition of What If?, we pose the question: What if a dirty bomb explodes in your hometown?

This would invariably create a cascade of unpredictable events. To explore as many possible outcomes and viewpoints, RECOIL OFFGRID asked three different survival writers whether they would hunker down or hit the road. For this installment, we have Candice Horner, a U.S. Marine Corps veteran, registered nurse, and competitive shooter with experience in federal law enforcement. Next is Mike Seeklander, a former law enforcement officer who’s also a Marine Corps combat veteran, firearms instructor, and a martial artist.

And for contestant number three, our editor asked me to craft a story as well. I’ve been teaching people how to survive almost everything for the past 20 years, and I’ve written New York Times-bestselling survival manuals.

And now it’s time to find out just how prepared we really are.

The Scenario

SITUATION TYPE

Terrorist attack

YOUR CREW

You (mid 20s) and your 3-month-old baby

LOCATION

Baltimore, Maryland

SEASON

Autumn (October)

WEATHER

Cloudy, 63 degrees F, with slight wind

The Setup: You’re an electrician in your mid 20s. Recently separated from her deadbeat mom, you now have sole custody of your infant, Ashley. With your babysitter (your mom) on vacation, you also take a two-week vacation to spend some quality time with Ashley in your townhouse in the Federal Hill neighborhood. In the shadow of our nation’s capital, Baltimore can be a rough city — you consider the government dysfunctional, the infrastructure in disrepair, and the crime rate impressively high; but it’s home.

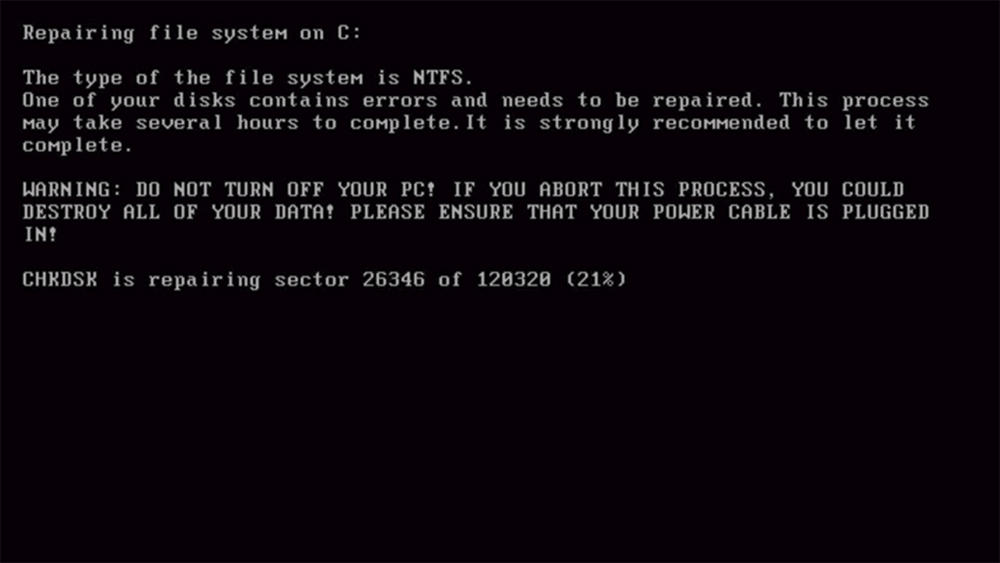

Just as you introduce Ashley to the glory of televised Ravens football, you hear a distant boom followed by some rumbling. Then the texts, tweets, and posts start flooding your smartphone. Something about a building collapse. Next, the commentators stop their pregame show to report there was some sort of explosion at Johns Hopkins University. A big one. Eventually, the network’s breaking news alert interrupts the game: A massive explosion has vaporized the campus’ entire School of Education building on Charles Street and destroyed much of the surrounding residential and business buildings. Terrorist attack? Unless it’s the biggest gas leak accident ever, most likely.

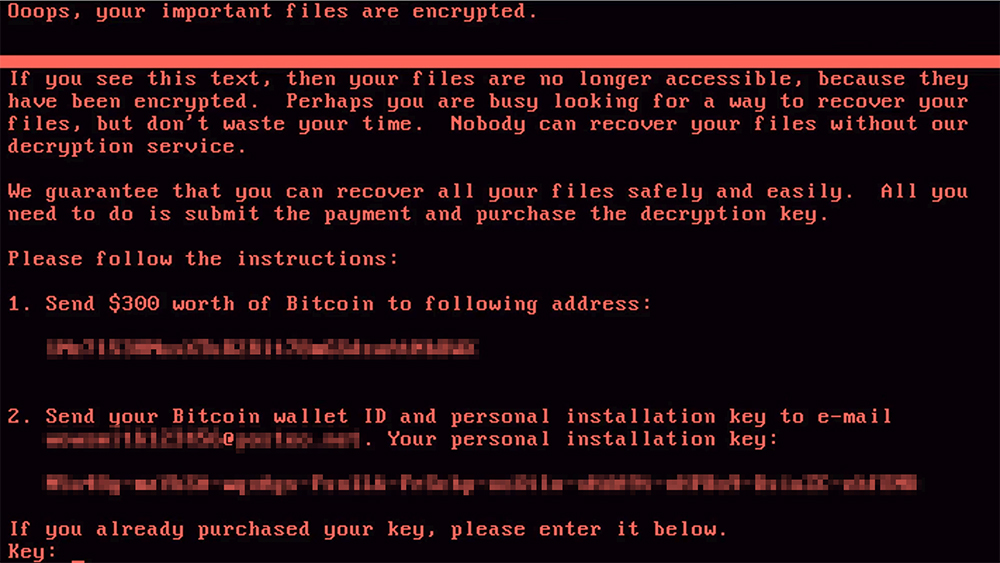

The Complication: As news reports grow scarier by the minute, you realize you can’t go numb. After putting Ashley down to sleep, you start gathering your supplies and gear. That’s when you see the TV and online updates: ISIS has claimed responsibility for the explosion, saying it was a truck bomb laced with radioactive material. They say they struck at “the heart of a blasphemous education system that teaches Americans how to hate Islam.” The phrase “dirty bomb” echoes in your head, stopped only by another ISIS threat: “There will be more.”

The New Plan: You don’t know if there’ll be another attack that’s closer, but you know that the university is only 5 miles away. And if that attack really was a dirty bomb, exposure to radioactive debris could spell bad news — and you’re not willing to do nothing with Ashley in your care. So, do you use your preps, supplies, and survival skills to shelter in place and fortify your townhouse? Or do you grab your baby, climb into your work truck, and hope to get as much distance between you and any possible fallout or follow-up attack?

Former U.S. Marine: Candice Horner’s Approach

In an instant, the city went into a synchronized panic. Screams of terror seemed to come from all directions. Word had quickly spread that ISIS was responsible for the bombing. I didn’t need to look outside to know the city was in chaos.

I love Baltimore, but unfortunately I’ve seen firsthand how quickly a crowd can turn into a violent mob. Because the news reporters were providing conflicting statements, I had to believe no one actually knew the full story. With limited information, but enough to know it was dangerous outside, I decided we were staying put.

I quickly scanned the Internet to get a Cliff’s Notes version of how to survive a dirty bomb attack. Most of what I found advised staying inside if we were already sheltered in a safe place at the time of the attack. I wasn’t sure if we were upwind or not, but I figured I could look into that once I had a clear plan for our “staycation.”

I double-checked to make sure we had enough food, water, baby formula, diapers, and wipes to tide us over for a few days. After scooping up Ashley and her Pack ’n’ Play, we headed down to the basement, which doubles as my man cave.

My man cave has many comforts, but a bathroom is not one of them. A 5-gallon bucket with a lid became my makeshift throne. The small windows in the basement were old and could potentially leave and allow the infiltration of radiologic dust, so I sealed them with duct tape. My paranoia took me a step further by cutting my shower curtain liner slightly larger than each window and completely covering the frame and again sealing it with duct tape. Even though the heat wasn’t running, I shut off the air system and taped the air vents in the basement. If there was dirty bomb dust outside, it was going to have one hell of a time getting into my safe haven.

Ashley was sound asleep by the time I finished taping the air vents. The sight of her peaceful slumber had a calming effect on me. I sat down, closed my eyes, and focused on the feeling of clean air rushing into my nose and then slowly exhaling out of my mouth. In that moment, all I thought about was the blessing of those breaths.

Then, déjà vu erupted, but from a different direction. ISIS meant what they said, and initial news reports said they annihilated Fort McHenry with another dirty bomb. Not only were we now sandwiched between two dirty bombs, but these bastards also destroyed the birthplace of our national anthem. Fearing things were getting worse by the second, I ran upstairs to get my shotgun and extra 00 buck just in case local punks took advantage of the situation to loot homes and businesses.

On the way back down, I grabbed the air purifier so the basement wouldn’t get stuffy while we waited out this nightmare. The most terrifying aspect of the whole situation was not knowing what to do, or how long we would be in danger. I had the news on TV, the radio on, and the Baltimore Police Department scanner broadcasting via my laptop. Although I loathe social media, Twitter provided the most up-to-date information from eyewitnesses. The hashtag #baltimorebomb was in full effect.

I needed to learn more, but part of me didn’t want to delve deeper only to find my man cave could quickly turn into our coffin. I had to mentally compartmentalize the turn of events so that I could be productive and, if nothing else, attempt to prepare for our doom. I looked up the current wind direction report online. The wind was drifting slowly northeast. This meant the dust from the first bomb wouldn’t come near us, but the fallout from Fort McHenry could hit us.

Because the windows of my house were drafty, I was concerned they’d let radiologic dust in and possibly slip into the basement via the door. I taped up and covered the basement door in the same fashion as the windows. My mother sent me a frantic email that she’d been trying to call. Everyone must have been calling their loved ones in Baltimore, because I couldn’t call her back. Thankfully, the Internet was working, and I was able to give email and Facebook updates to everyone who wanted to make sure sweet Ashley and I hadn’t perished. Being connected while bugging in was reassuring and it ever-so-slightly softened the hard edge of doom surrounding us.

It had only been three hours since the first bomb, and the future possibilities were slowly setting into my mind. I’d do anything to go back to yesterday, as mediocre as it was. The day prior to the bombings was normal; I came home from work and had the usual discontent toward my job, but loved the life I could live thanks to it. The sounds of cars driving down my street and kids laughing on the stoop next door were now replaced with rumbles of a city in distress.

Hopelessness set in, my heart sank, and I closed my eyes. I guess stress had gotten to me so much that I passed out from mental exhaustion. I was startled awake by high-pitched screams coming from the street.

I peeled back the shower liner from the window and saw my elderly neighbor, Ms. Thompson, kneeling on the sidewalk cursing the sky. She looked angered, but equally terrified. I knew she lived alone. I assessed the situation for what seemed like an eternity. I felt like I should help her, but I didn’t want to put Ashley or myself at risk.

Ashley started crying. Luckily she wasn’t old enough to comprehend what was going on — she was just hungry. But I had to go help Ms. Thompson; she was going to scare herself to death. Peeling back the barrier on the door upstairs felt like a knife to my gut. I got over myself and pushed forward with my rescue mission. As soon as Ms. Thompson saw me, the look on her face affirmed my decision to help. She was relieved. Once we got inside, I instructed her to take a shower in the extra bathroom to wash off any possible radioactive material, and to put her clothes in a plastic bag. I gave her a set of Ravens sweats and told her I’d meet her in the basement. Since I had gone outside, I followed my own directions and took a shower in the master bath, albeit without a shower curtain, before returning to the basement.

By nightfall, Ms. Thompson was very sick. She had continuous bouts of vomiting; she was drenched in sweat and became lethargic. The next morning I was able to get a call through to 911, and they said someone would be there as soon as possible. As soon as possible is a relative term, and they were able to take her to the hospital the following night. Once she was in capable hands, I was able to make the most out of my basement retreat with Ashley.

Disaster relief workers took us to a safe area five days later. But, we still weren’t out of the weeds since the effects of the fallout could take weeks to show. Baltimore would never be the same.

Former Law Enforcement Officer: Mike Seeklander’s Approach

I remembered my parents’ reaction when the Twin Towers fell in New York City, the horror on their faces. As a 10-year-old at the time, I had no idea the emotions they felt — until today. Now father of a beautiful girl, I truly understood what it meant to have kin possibly face harm or even death. My gut told me that the explosion was only the beginning, and, if ISIS repeated the pattern that Osama Bin Laden planned 15 years ago, there were certainly other targets.

“Move!” I heard my father’s voice in my head. A former U.S. Marine (there are “no ex-Marines, just Marines”), he would always say action trumps intent every single time. I had to act, and speed was of the essence.

Baltimore was both beautiful and sinister, and I knew from experience that when things went bad, the bad people came out. My lovely city had one of the highest crime rates around, and if food, water, and power started to dry up, all hell would break loose. Not to mention there was a dangerous cloud of potentially radioactive dust headed in who knows what direction. And there was no hope in waiting for the government to step in. I figured they would be suffering from HUA (head up ass) disease for at least several days before reacting properly. Nope. Time to bug out.

And thanks to being raised by a Marine, I knew what to do. When I was a kid, we’d often head out with minimal gear and tell my mother that we’d be back the next morning. While these outings were only a mile or so into the wooded area behind our house, each excursion taught me something new. The one constant? Always make a packing list. I know, it didn’t really sound like such a cool survival lesson. But the way it worked with my old man was that if you forgot something, you lived a night without it. Forgot your bug spray? Live with ticks. Forgot your fire-building kit? Sleep cold.

A packing list was a great tool for gathering the right items quickly, but also something you could tweak depending on your trip. Because I would be jumping into my work truck — a 2011 Toyota Tundra Rock Warrior 4×4 outfitted with the tools of my trade — I had plenty of room to pack the essentials.

My goal wasn’t to grab my baby and live off the land for an extended period of time, but rather get clear of the crime-ridden areas with the potential to succeed in any environment that I ended up in. My destination was one that I lucked upon several years ago while on a project. A longtime customer, a rich dentist named Richard, hired me to do a complete wire job of his family’s old cabin that he inherited. It was on secluded acreage near Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. If I helped keep the place up and do any electrical work he needed, I had a key and free access.

The cabin was about 100 miles northwest of Baltimore — well outside of any potential radioactive dust cloud and far north of other potential targets, such as Annapolis and Washington, D.C., but not so far that I couldn’t reach it by truck with my spare fuel cans.

I opted for my full camping kit plus a few creature comforts for Ashley. This included a small tent, air mattress, sleeping bag, fire-starting kit, solar charger, and my drop box of small supplies — ranging from silverware to a coffee pot. While I had plenty of comfort items at the lodge, I had many miles to cover to get there and had no idea what I might encounter.

Next, I stowed my Smith & Wesson M&P 9C and two spare magazines into a Vertx sling bag then placed my Marlin 336BL lever-action rifle and a .30-30 Winchester with an 18-inch barrel in a secured compartment in the truck bed. After double-checking my list, I headed out. Total packing time: about 25 minutes, getting me out ahead of the mass of panicked fans leaving the football stadium.

Luckily, my job required a lot of driving, so I knew how to navigate through my Federal Hill neighborhood without hitting the major thoroughfares. My goal was to avoid Interstate 95 and 83 altogether and instead use surface streets to eventually get to Maryland Route 26, which would take me northwest to my destination.

All was going well until the 26 neared the Interstate 695. I could see the line of traffic ahead of me. I wasn’t sure if the jam was caused by panicked drivers or it might actually be a roadblock set up by law enforcement.

Based on the radio reports, there were at least two more explosions, and now at least two cells of terrorists were playing hide and seek with local and state police. Several gun battles had erupted, and the city was placing all residents on a lockdown, warning them to stay inside their homes. And while I appreciated what the police were trying to do, there was no way I was getting trapped inside the Baltimore metro area covered with a cloud of potentially radioactive material and relying on the government to save me.

As traffic inched forward, I was able to switch lanes and get out from behind a semi-truck. I could see police lights in the distance; no doubt a road block. Sitting like a frog stuck in mud was not an option. I decided to do something about it.

One thing I had learned from years of camping and off-roading was that there was almost always a way around an obstacle, especially on the East Coast with hundreds of years of old trails and small winding roads. I drove up onto the curb, cutting into the parking lot of a restaurant to double back. I found a set of residential streets that paralleled the roadblock and knew that if I could navigate another half mile west I could probably jump back on a main road and be good to go. A few backtracks later I finally found a decent route and made it back to the 26.

After an intense first hour trying to bug out from the Baltimore area and a smooth 90 minutes after that, we finally rolled up to the Chambersburg property. Exhausted, I took Ashley out of her car seat and put her in a baby carrier on my chest. As I was about to grab the baby bug-out bag I had packed, a silhouette stepped out from behind a bush. Instinctively, I grabbed the M&P handgun from my sling bag and kept it in the low ready position as I turned.

I breathed a huge sigh of relief to find it was Richard, the dentist and cabin owner.

“Thank God you made it,” he said, stepping forward like he just saw a ghost. He was at the cabin with his family for a weekend trip and had heard the news about the attacks. I discreetly put the gun away, opened the truck door, and gave him an embrace. I had never been so happy to see a dentist before.

Survival Expert: Tim Macwelch’s Approach

Leave or stay? The debate raged in my mind. Every instinct urged me to flee, but I knew how bad traffic was in Baltimore at rush hour. And a panicked exodus out of the city would be worse than any rush hour imaginable. The friendly flat screen TV that was about to show my favorite football team was spewing forth information that I just didn’t want to hear. ISIS was threatening more attacks in my area, and the emergency broadcast system was instructing people to “shelter in place.”

I didn’t want my little girl to breathe radioactive dust. I just wanted to get out of town. But I knew the traffic could turn into gridlock in a heartbeat and just one automobile accident could leave thousands of people trapped in their cars — with no shelter from the tainted air. Despite the fact that every fiber of my body wanted to put my sleeping baby in my work truck and drive away, I knew I had to stay put. It was the only logical choice, and after several minutes, I finally came to grips with it.

But how could I make sure the air in our poorly insulated townhouse was safe to breathe? I didn’t have duct tape and tarps to keep the dust from creeping in, and I wasn’t even sure which way the wind was blowing that day. Did I have time to seal off all the windows in one room, or would the wind blow all of the dust out over the water and away from our home? I just didn’t know.

I had to find out if we were in harm’s way. Pulling out my phone and searching for weather maps with wind direction and speed, I found a weather webpage from a local news station. Thank God, I thought — the wind wasn’t blowing from the university toward my house. But it was blowing between my home and the school.

Then the situation finally hit me. The bombing site was a busy university. All those people, dead or dying. I felt as if I’d throw up, but I knew I had to control my emotions.

The wind wasn’t blowing the dust in my direction at that time, but that could change with a moment’s notice. I had to seal up my daughter’s room, but I didn’t have the duct tape and plastic sheeting recommended for shelter-in-place situations. I did have plenty of electrical tape in my work truck. I quickly ran out to the vehicle, astonished by all the people in the street. They were watching the smoke cloud rise into the sky and drift to the south. “You should all stay inside!” I yelled to a few of my neighbors. They looked at me questioningly, as if they didn’t understand what I said. But I didn’t have time to stop and explain the situation.

I unlocked the truck, grabbed a cardboard box of black electrical tape, and headed back inside. I had 15 tape rolls, and I wasn’t afraid to use them. I locked the front door and taped the door cracks behind me. Then, I headed to Ashley’s room and taped the cracks around the window sashes. I taped the electrical outlets and light switch, as well as the HVAC duct in the floor.

After doing all that, I went over everything again with more tape, making wider seals. I hurried to the kitchen, and filling up a grocery bag with clean bottles, nipples, and pacifiers. Then, grabbing a can of formula and a jug of distilled water, I stashed all these things in my baby’s room. Finally, I grabbed my get-out-of-Dodge bag and all the drinks from the fridge and headed to the baby’s room. I looked at the weather on my phone again, hoping that the wind hadn’t shifted my way — thankfully it hadn’t. I cracked open a beer as quietly as I could to avoid waking Ashley and took a long swig of the cold brew. But just as I started to feel like I had everything under control, all hell broke loose.

A second explosion rocked the city of Baltimore, much closer to my home this time. The old windows in the baby’s room rattled and one of the panes cracked.

Ashley awoke from her nap, screaming. This was the ISIS threat made real. And much closer to home. I rushed to tape the crack in the window pane and check all of the tape strips for a good seal.

Through the one window of my child’s room, I saw a hazy smoke begin to pass by the window. The dread built as I realized that I was smelling smoke. This meant that the outside air was still getting in. I’d worked in these houses for years as an electrician, and I knew just how shoddy the construction was, but now these half-assed homes were a real threat. I checked all the tape again with my right hand, holding and bouncing the baby in the crook of my left arm to calm her. I could still smell the smoke and dust, but all the tape was tight. How was I going to keep the dirty air out? I stressed. If only I had a way to pressurize the room.

Then it hit me — my uncle’s carpentry tools! When the housing bubble burst on the East Coast, a lot of small construction companies went out of business. My uncle was among them, and he asked me to store a few of his power tools, including an air compressor. I pulled open the bedroom door, breaking the tape seal, and ran to the basement. The air seemed musty, but much cleaner down there, and I plugged in the compressor unit. The loud motor kicked on and soon the large tank was full of air.

Rushing back upstairs, I re-taped the door and put a small nick in the hose with the tip of my pocketknife. The air hissed out very slowly, and as I held my daughter, I aimed the leaking air toward our faces. After a few minutes of this, the smoke smell didn’t seem so noticeable. “This might be working, baby” I said to my little one. Maybe the air pressure in the room was higher than that outside the room, and it would keep the dust and smoke at bay.

The air had cleared outside of the window, and it seemed that an autumn breeze had picked up. Maybe we might just make it, I thought. Maybe.

Conclusion

There’s nothing that isn’t alarming about a dirty bomb, but it isn’t quite as dangerous as it sounds. Of course, anyone in the blast radius of any bomb is at great risk for traumatic injury or death, but what terrorists would be banking on with a dirty bomb is a greater panic due to the inclusion of a scary substance, namely something radioactive.

Sure, radiation is bad and enough of it can kill you, but a dirty bomb is hardly a nuclear warhead. Avoid the dust, stay indoors, let the prevailing winds disperse the dust and smoke, and — above all — don’t panic. It’s likely that you’d get more radiation in a dentist’s office than in a city that’s been dirty bombed, and when we panic, the bad guys get the exact reaction that they want. (For more, see our article on Dirty Bombs).

Meet Our Panel

Tim MacWelch

Tim MacWelch

Tim MacWelch has been a survival instructor for more than 20 years, training people from all walks of life, including members from all branches of the U.S. Armed Forces, the State Department, DOD, and DOJ personnel. He’s a frequent public speaker for preparedness groups and events. He’s also the author of three New York Times-bestselling survival books, and the new Ultimate Bushcraft Survival Manual. When he’s not teaching survival or writing about it, MacWelch lives a self-reliant lifestyle with his family in Virginia. Check out his wide range of hands-on training courses that are open to the public at www.advancedsurvivaltraining.com.

Candice Horner

Candice Horner

Candice Horner has the heart of a prepper, but the traveling schedule of a gypsy. Ever resourceful, this U.S. Marine Corps veteran and emergency room/prison nurse has a honed and refined skillset, focusing on adaptability and utilizing the tools on-hand. As a competitive shooter, Horner is often on the road, so she’s usually rolling with a go-bag, a survivalist mentality, and enough firepower to have your back in a SHTF scenario. www.recoilweb.com / www.candi323.com

Mike Seeklander

Mike Seeklander

Mike Seeklander is the owner of Shooting-Performance LLC, a full-service training company and co-hosts The Best Defense, the Outdoor Channel’s leading firearm instructional TV show. In addition to being a U.S. Marine Corps combat veteran, a former law enforcement officer, and a competitive shooting champion, he’s an accomplished martial-arts instructor and holds multiple ranks. Learn more about him at: www.shooting-performance.com

More From Issue 16

Don’t miss essential survival insights—sign up for Recoil Offgrid’s free newsletter today.

Read articles from the next issue of Recoil Offgrid: Issue 17

Read articles from the previous issue of Recoil Offgrid: Issue 15

Check out our other publications on the web: Recoil | Gun Digest | Blade | RecoilTV | RECOILtv (YouTube)

Editor’s Note: This article has been modified from its original print version for the web.

Tim MacWelch

Tim MacWelch Candice Horner

Candice Horner Mike Seeklander

Mike Seeklander