Warning!The content in this story is provided for illustrative purposes only and not meant to be construed as advice or instruction. Seek a reputable self-defense school first. Any use of the information contained in this article shall be solely at the reader’s risk. This publication and its contributors are not responsible for any potential injuries.

Paracord is to the survivalist as ketchup is to French fries. Carried in hanks, bracelets, shoelaces, neck-knife lanyards, and all over, paracord is a staple piece of kit. But it’s one thing to have some on hand; it’s another to know how to actually use it. Many people look at paracord and see a piece of string. We look at paracord and see endless possibilities to increase our survivability.

This is knot your average cordage article. We were provided with plenty of paracord from Campingsurvival.com, and we’re here to take your skills and readiness to the next level with these RECOIL OFFGRID projects.

Paracord Project #1 – Trapo

Function: Weapon

Difficulty: 5 out of 5

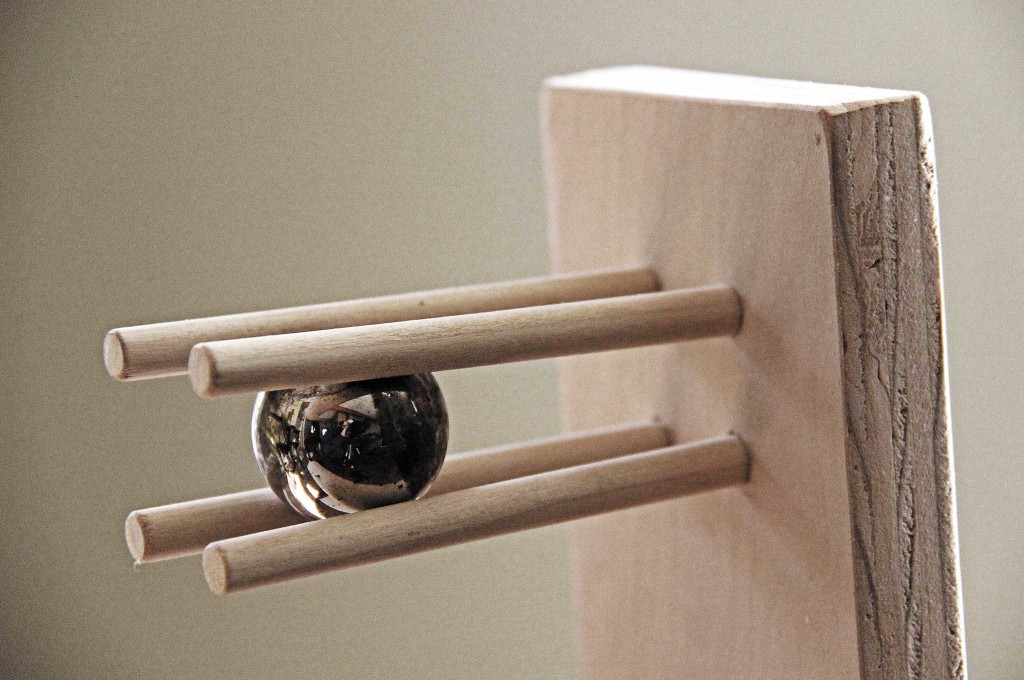

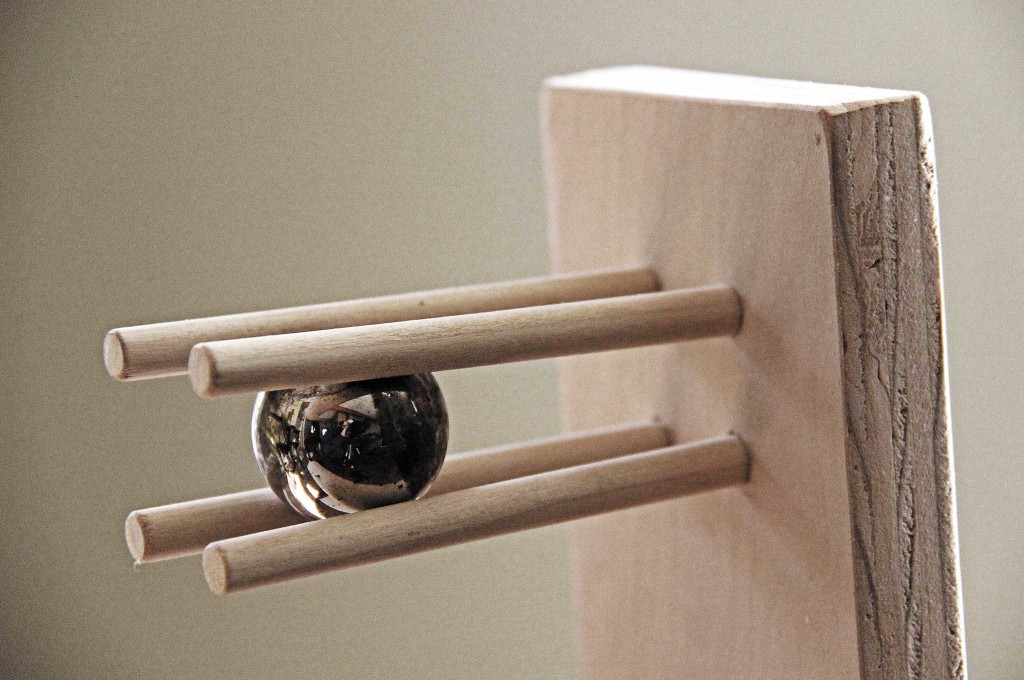

How To: Anyone who has seen the Steven Seagal movie Out for Justice knows what a rock in a sock is even if they don’t know why Ritchie killed Bobby Lupo. Here’s how to make one out of paracord with a ball bearing. This version requires knowledge of how to tie a monkey’s fist knot around a solid sphere.

Start by passing your paracord around the object enough times to cover it. For a 1-inch ball bearing, this is approximately six passes of paracord. Wrap your cord perpendicular to these passes six more times. Thread your paracord another six times to the inside of the second set of passes and around the first set of passes (there’s a reason for the difficulty rating on this one, and you just read it). Dress up the knot by pulling it here and there until it tightens around the ball bearing. Tie the ends into loop that can be slipped around your wrist and flail away.

Monkey fist knots can be tied by hand, but a simple jig made out of wooden dowels and a couple pieces of board make...

Notes: We’ve tied these by hand without a jig and must admit it’s worth the extra steps to assemble one. Not since puberty have you wished as much for an extra hand to help out in in the process. Just drill four holes, 1 inch square, into a wooden board and insert wooden dowels to hold your ball bearing for you.

Paracord Project #2 – Friction Saw

Function: Cutting synthetic materials

Difficulty: 1 out of 5

How To: All that’s needed to create a paracord saw is a length of paracord (braided Kevlar cord works well, too, and that’s why we carry it in our wallets) with a couple loops tied in each end, large enough for your hands.

With the saw tied, place it over whatever you plan to cut and run it back and forth, increasing the friction and heat on your work piece, while dispersing the heat over the length of the saw. This will cut through duct tape, webbing, PVC pipe, or just about anything synthetic.

A paracord friction saw works by running the cord over a synthetic object like this PVC pipe. With enough heat, the saw...

Notes: Watch your hands with this one. Your saw will be hot when you’re done. The longer the saw, the more room to disperse the heat.

Paracord Project #3 – Improvised Tourniquet

Function: Stop bleeding

Difficulty: 2 out of 5

How To: A tourniquet should always be applied “high and tight.” That is, placed up high on the arm near the armpit or up against the crotch. In general, paracord sucks as a tourniquet, as it’s too narrow to avoid causing damage to tissue. However, when multiple strands are tied as one, it’ll work in a pinch.

Tie a single square knot with multiple strands by passing left over right, tying a knot then right over left and tying a knot. Insert a tactical pen (or something else that will serve as a turnbuckle). If you can, put a key chain split ring around the strands first so you have a place to tuck that pen once tension is applied. Leave it on, and get your buddy or yourself to the emergency room.

A single strand of paracord makes a horrible tourniquet. Multiple strands tied as one will work well to prevent...

Notes: While you can do this with paracord, get in the habit of carrying a real tourniquet. They’re cheap and highly effective. What’s your life worth?

Paracord Project #4 – Improvised Harness

Function: Weight carrying (read advisory below)

Difficulty: 3 out of 5

How To: You may need to escape a high rise or descend a cliff. If you have no other option, here’s a solution. A traditional Swiss seat is tied with about 12 to 15 feet of flat webbing or rope. For comfort, you should use multiple strands of paracord unless you want that tourniquet effect from the previous project.

Once you have your cordage ready, find the center and hold it at your side by your waist. Pass one end around your waist and meet in the middle. Create a surgeon’s knot with the two ends. Take the two ends and pass them under your ass. Put the ends over your shoulders and stand up to pull them tight. Pass the ends back through the paracord waistband you made and tie each off with a half hitch. This is the point where you’ll feel a pinch between your legs. Remember, it’s life or limb – or in this case life or sack.

Take the ends of your harness and tie them off with a square knot and backup knots, to your left if you’re a righty and to the right if you’re a lefty. Make sure your knot is on the opposite side of your brake hand. If you’re wearing a sturdy belt, pass your carabiner through that too, making sure the gate opens toward you. The spine of the carabiner is where your munter hitch will be used for rappelling. The majority of your weight will be supported by your paracord leg loops. This works even better with flat webbing, but can work with what you have.

Keep the gate of your locking carabiner facing you when you clip in. This allows the rope to work against the spine of...

The author rappelling with a paracord harness. While you can do this, it isn’t nearly as comfortable as a...

Notes: Seek professional climbing and rope instruction before trying this one at home. Rappelling is inherently dangerous. However, even more dangerous than rappelling in an emergency is doing nothing when SHTF. That could lead to death.

Paracord Project #5 – 1-2-3 Anchor

Function: Vehicle recovery anchor

Difficulty: 4 out of 5

How To: Cut six 1- to 2-inch diameter wooden stakes, measuring approximately 18 inches long. Pound the first stake into the ground at a slight angle in the direction you want your stuck vehicle to go. Don’t make this angle too great. From your initial stake, pound the next two stakes about 1 foot further away on each side at 45-degree angles left and right.

From these two stakes, pound the final three stakes another foot behind, continuing in a pyramid pattern. For those of you who have played Beirut/beer pong, this will be a familiar pattern. Tie a length of paracord from the top of the first wooden stake to the bottom of the two stakes off to 45-degree angles.

Tie paracord from the second row to the third row in a similar fashion. You can use a lark’s head on the top and a rolling hitch and half hitches on the bottom. Attach your come-a-long to the first stake and to your vehicle. The 1-2-3 anchor works well since the stakes are supported by the following rows.

1-2-3 anchoring requires cutting multiple posts and pounding them into the ground in a triangle stack. Having the right...

Notes: Vehicle recovery can be quite dangerous, even fatal at times. Make sure your vehicle parking brake is on while securing your anchor and off when using it. A small hammer and come-a-long makes retrieval easier than resorting to a Spanish Windlass (the Spanish Windlass will be featured in a future issue of RECOIL OFFGRID).

Paracord Project #6 – Tripod

Function: Suspending objects and much more

Difficulty: 3 out of 5

How To: Gather three poles and place them on the ground. They need not be the same length as the legs can be kicked out once assembled to make it stand straight. Wrap paracord around one of the poles with a lark’s head knot to start the tripod lashing. Then wrap the three poles three or four times.

The strength of the tripod lashing comes from frapping, when you pull the paracord in between the middle pole and pole closest to you and pull it tight to constrict on the wrapping on all three poles. Do it a second time between the middle pole and the pole furthest from you. Finish the tripod lashing by taking the end of the cord and securing it to the remaining end of the lark’s head knot.

Tripods are staples in traditional woodland basecamps. They can be used to create raised beds, camp kitchen potholders,...

Notes: Tripods can be used to suspend stew pots over the fire, to build raised beds in wet conditions, as camp furniture, or as the framework for a hauling “crane.” Anyone who wants to build advanced tripod projects should also know how to make a square lashing.

Paracord Project #7 – Bottle Carrier Net

Function: Holding bottles, containers, potted plants, etc.

Difficulty: 2 out of 5

How To: Measure eight lengths of cordage by placing it under your bottle and holding the ends over it. It should measure approximately three times the height of your bottle. For the bottle used in our tutorial, this meant approximately 6 feet in length for each cord.

Cut eight lengths of cord out of a 50-foot-long hank. The last 2 feet will be used to create a handle. Attach the eight strands to your split ring with lark’s head knots. The trick to this bottle carrier is tying knots with strands of cord adjacent to one another.

Tie the first overhand knot tied 3 inches from the ring, putting the knot on the side of the bottle rather than under it. From here, each knot works its way up the bottle every 1.5 inches. Try to keep your knots spread out consistently or it’ll look like rubbish. Continue working up the bottle until you get to the top. Finish the carrier by tying four of the strands together as one handle and the remaining four as the other handle.

Water bottle net carriers are more time consuming to make than they are difficult. Make sure to make your knots evenly...

Notes: This same pattern can be used on almost anything box-like or cylindrical in shape. Make sure your split ring can handle the weight, or use a welded ring available at hardware and boating stores. If you don’t like overhand knots, you can use square knots instead.

Paracord Project #8 – Turnbuckle Rattler

Function: Camp alert system

Difficulty: 5 out of 5

How To: When constructing the turnbuckle rattler, look for two sturdy trees with minimal flex in their trunks. This won’t work well with small diameter saplings. Take a length of paracord and wrap it around both trees. Tie an overhand knot in the paracord, leaving tail ends to your knot as well as very little slack in the loop you just created.

Just about one foot above the loop you just tied around the trees, tie another loop. From that, suspend a length of paracord down from the center in the gap between the trees and attach a few aluminum cans.

Cut a small wooden dowel from a tree branch or sapling. Put this dowel between the gap in the trees in the original loop and take up the slack in the loop by cranking the dowel end over end, increasing the tension. Slip a paracord loop over one end and attach it to a tripwire. When an unexpected guest enters your camp, they’ll trigger the turnbuckle rattler, striking the cans and alerting you to their presence.

Never be surprised in your camp by constructing a turnbuckle rattler with aluminum cans commonly found in the woods....

Notes: The difficulty rating in this trap is derived from the trigger and tripwire mechanism. A simple 90-degree toggle is all you need, but that requires knife carving knowledge and skill. When setting this alert system, watch your eyes. This device is under tension and disrespecting it can lead to accidental triggering.

Paracord Project #9 – Sling

Function: Weapon

Difficulty: 3 out of 5

How To: Paracord makes a great sling. For starters, determine what you plan to toss. For this tutorial, we’re using golf balls. On one end, create a loop for your middle finger. About 2 feet from this knot, create a pouch out of duct tape, a couple pieces of leather, or flat webbing.

Tie a second piece of paracord to this pouch; make it as long as the other side with the middle-finger loop. On this end, create a knot you can pinch. If you’re skilled at braiding, an entirely paracord version can be made with a web pouch. To streamline it, you can whip the paracord to the pouch with the inner strands.

Slings can be made with leather, nylon webbing, braided paracord, or even duct tape. They’re centuries old and...

Notes: This is easy to make but difficult to master. Try tossing this horizontally, vertically, or in a figure eight path. With enough practice you’ll be ready to kill that giant or challenge your skills.

Paracord Project #10 – Stretcher/Travois

Function: Moving an injured person

Difficulty: 3 out of 5

How To: Prior to starting, cut two poles at least one-and-half times the length of the person to be carried. If you’re making a travois, make them twice as long if you can. The poles should be sturdy and have minimal flex. Place them parallel to each other and as wide apart as your patient for a stretcher; cross them about a quarter of the way down in an “X” for a travois.

Tie your paracord to one pole, then directly across from it. About 25 feet should be enough to hold a patient. Don’t cut your cord! Continue zigzagging down your poles then back up again creating web work. Secure the end of your paracord and cover your web stretcher with a camping pad. It can be used without a pad, but for patient comfort, hook them up if you can.

Notes: A non-paracord version of a stretcher can be made with just a blanket and poles. Whether paracord or blanket, learn ways of helping your buddies out and teach them so they can help you in case you’re the one who screws up.

Source

Camping Survival

www.CampingSurvival.com

Beyond Paracord

The 550 paracord is the industry standard when it comes to cordage. It’s a great baseline of comparison for other types of ropes. For example, tarred bank line is referred to as “thinner than paracord,” and jute twine is said to be “not as strong as paracord.” As outdoor enthusiasts, we hold 550 paracord in high regard, but there are times when other options may be better. Here are a few other cordage options to carry next to the hanks of paracord in your pack.

Braided Kevlar: This line is ridiculously tough. Thinner than 550 paracord, it has much more strength pound for pound. It’s harder to cut and knot, but the tradeoff is packability.

Jute Twine: You don’t always need 550 pounds of breaking strength, and there are times when you want to tie something up in camp and not worry about taking it down. Jute twine isn’t synthetic and can be left behind to biodegrade. That’ll make the tree huggers in your group happy.

SpiderWire Braided Line: This fishing line is the only type we trust. If you can catch a 50-pound freshwater fish, you’re a stud. All other fish can be landed without worrying about breakage with this super line. Rather than using one of the inner strands of paracord, use this dedicated line. Just watch your fingers if you hook onto a fish and it runs. It’ll slice your skin like a laser.

Dental Floss: Wicked strong, pre-rolled into cute spools, and dentist-approved, this is handy cordage. Waxed floss is great for whipping lines that’ll unravel, and it also works well for setting up traps. When visiting your dentist, ask for samples. Rip them out of the packaging and tuck them into your pack pockets.