In This Article

Photography by Trevor Reed, and courtesy of AMC, The Department of Energy, Diesel Power Magazine, and the manufacturers.

This article was originally published in Issue 1 of our magazine.

Unfortunately, it’s not very hard to imagine a scenario where the fuel supply system breaks down. In 2012, the closure of just two refineries in California caused fuel prices to skyrocket and some stations to close in a state with more than 38-million people. Now, picture every refinery in the entire country, or even the whole world, shutting down, and record-high prices will seem like a minor inconvenience as supplies of ready-to-use fuel disappear. One way to insulate yourself from this kind of disaster is to learn how to find and make your own fuel before it happens, and biodiesel is your best bet for self-sufficiency.

Above: You don’t need to be an expert chemist or wear a hazard suit and mask to make your own biodiesel at home. Friends may be tempted to call you Mr. White when you start creating batches of crystal-clear biodiesel, but you’ll be laughing all the way to the bank, when your fuel costs drop below $1 per gallon.

What Is Biodiesel?

The “bio” in biodiesel is there because the fuel comes from biological resources, instead of petroleum. Biodiesel can be made from a number of sources, including vegetable oils, animal fat, used deep-fryer grease, or even butter. It’s made by brewing these substances and then adding chemicals and water to maximize consistency and strip away impurities. The byproduct of this chemical reaction is glycerin, which can be used to make soap, lotion, and other products, or sold to recoup your production costs.

Why Biodiesel?

Availability when petroleum supplies are scarce is not the only reason to choose biodiesel as your fuel of choice. Imagine a substance that doesn’t need to be made at a refinery, that’s more powerful than gasoline, gets more miles per gallon than gas, while costing and polluting less than diesel, and you have biodiesel. In addition to powering a vehicle’s engine, biodiesel can also run a diesel generator, or be used as heating oil. Diesel engines are known for being powerful, efficient, and durable, which makes them ideal for an emergency situation. That’s the reason tractors, heavy equipment, and semi-trucks run on diesel.

Petroleum-based diesel fuel contains more power per gallon than gasoline, and biodiesel is just as potent, but you can make it at home. Plus, engines that run on diesel aren’t nearly as picky as gasoline engines when it comes to the fuel you can use, which means they can be a lot more flexible, and useful, during an urban emergency. A diesel engine that’s been prepared to use biodiesel can also run on numerous petroleum-based oils you may acquire during an emergency.

Do It Yourself

In addition to costing significantly less per gallon than petroleum diesel, you don’t need a Ph.D. in chemistry to make your own biodiesel. The government may even subsidize some of your equipment costs with alternative-fuel tax breaks. All you need is a processor kit, which you can buy ready to use, or make for yourself, and some methanol and lye to mix with your source material. The size of your operation can range from about 40 gallons per batch to more than 400 gallons, depending on how much space you have available and how mobile your setup needs to be. Other than methanol and lye needed for processing, the only limitation to your biodiesel production will be how much organic material you can cultivate or obtain.

Above Left: This processor by Biodiesel-Kits-Online is made in the USA and can produce as much as 135 gallons per day. It has everything needed to convert biodiesel at home from start to finish. The company also makes a larger three-tank unit that can make as much as 270 gallons per day.

Above Right: The BioPro line of products by Springboard Biodiesel automates the production process to the point where the user only has to interact with the machine one time after it’s started. The BioPro 190 seen here can make 50 gallons per batch, and there is a larger model that can make 100 gallons per cycle.

Above: Graydon Blair of Utah Biodiesel Supply designed this system for a customer, using parts that can easily be repaired or replaced. The 80-gallon processor is made from an electric water heater, and the wash tanks are made from poly barrels. Quick connects are used to make operation a breeze and the wash tanks are mounted on a cart with wheels, so it can be easily moved to where the fuel is needed.

Emergency Sources

Under normal circumstances, there are quite a few legitimate sources for the ingredients to make biodiesel. Many businesses such as restaurants, buildings with cafeterias, and food-processing plants pay to have waste oil removed and will allow you to take it for making biodiesel. You can also grow your own sources, including seeds or vegetables that produce high levels of oil you can convert. These include, but are definitely not limited to, peanuts, sunflower seeds, olives, canola, and soybeans.

During an emergency, fuels that can be used in a diesel engine can be found in numerous places, including unused vehicles and equipment, and diesel generators from abandoned buildings; there’s even mineral oil in high-voltage power line transformers that are no longer in use. Like biodiesel, oils can be combined with petroleum diesel to extend the range of a fuel tank. With the right preparations, there’s hope you won’t have to resort to scavenging for fuel sources and can rely on your own stockpiles and even grow your own fuel supplies.

Above: Heads up! During an emergency, fuel sources for diesel engines can be found in lots of unexpected places. Power line transformers are full of mineral oil that can be used as diesel fuel if times become desperate. Of course, obtaining this type of fuel is illegal, and much more dangerous than making biodiesel, which is fairly safe. But in a long-term grid-down scenario it may be an option.

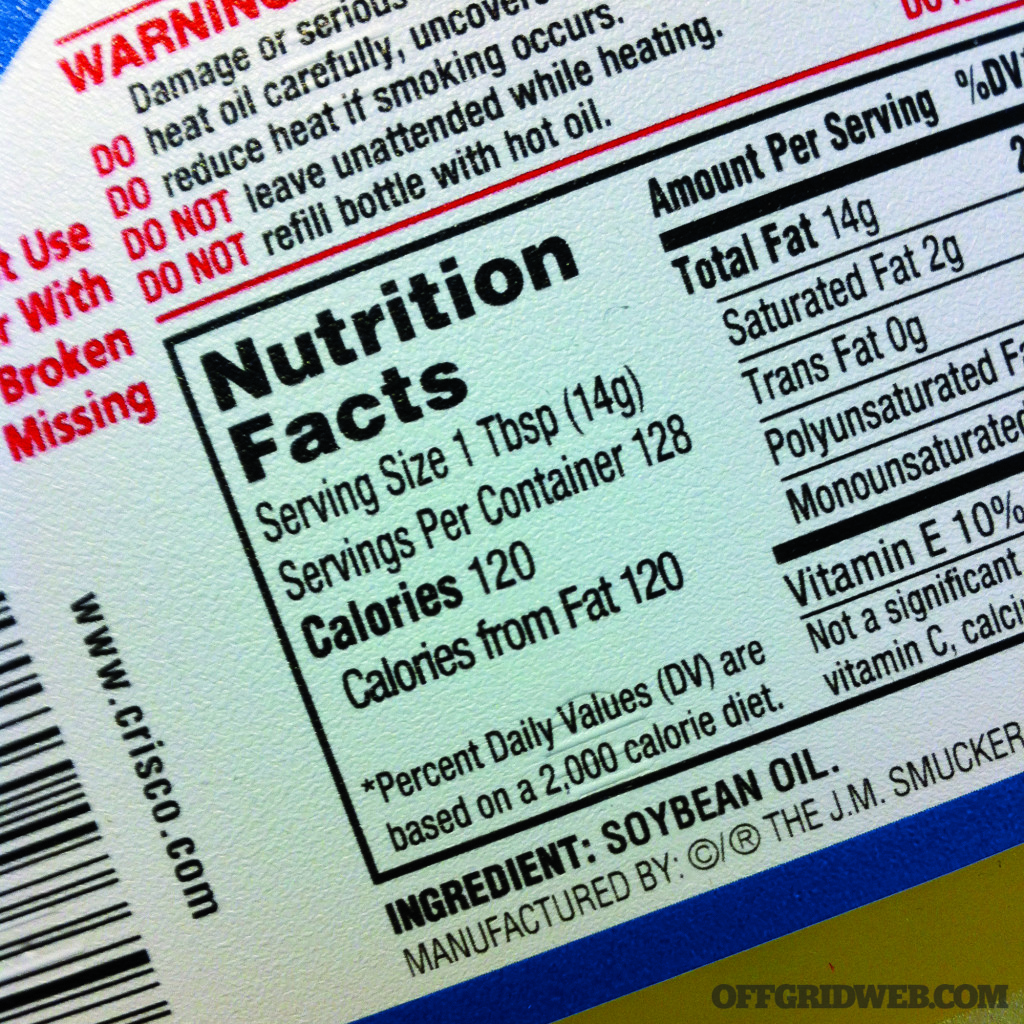

Cooking oil often has just one ingredient: soybean oil. This makes it an ideal candidate for making biodiesel, because it’s simple and clean, compared to used oils. Unlike used oil, cooking oil is not free for the taking, but it can be bought in bulk, and during an emergency, abandoned businesses may have lots of it on hand.

Sometimes biodiesel vehicles are called “grease cars,” because used cooking oil and grease can be converted into biodiesel. When used cooking materials are collected, they are first run through a screen to remove debris, and any particles that are not removed during the biodiesel conversion are caught by a filter when the fuel is transferred to a storage tank.

Biodiesel Engine Prep

Most modern diesel engines come from the factory ready to accept either 5 or 20 percent biodiesel, known as B5 or B20, mixed in with petroleum diesel. That means even some of the most advanced diesel engines will require no modifications to run diesel, which has been combined with biodiesel, and can extend your funds and your supplies. When it comes to using pure biodiesel, called B100, it’s best to make some modifications to your fuel system to ensure reliability.

Above: The famed Cummins B-series engine has just six cylinders, but it is world famous for its strength and durability. It’s not uncommon to hear about these engines lasting for 200,000, 300,000 or even more miles. These “bullet-proof” engines can be found in vehicles ranging from pickups, to motor homes, and heavy-duty trucks. With more than 2 million of these engines built for Dodge Ram pickups alone, there should be plenty of spare parts available during an emergency.

Low temperatures cause the most problems for vehicles running B100 because it can turn into a gel and clog fuel lines, injectors, and filters. These problems can be avoided with the help of products such as an electric heater in the fuel tank, insulation, and an inline heater in the fuel line. People who run straight vegetable oil (SVO), which is oil that has not been converted to biodiesel, will sometimes employ a two-tank system that allows them to flush regular diesel into the engine at start-up and before the engine is stopped to prevent gel from forming in the fuel system while parked.

Another concern about using biodiesel is the potential for water or debris to be in the fuel. While correctly processing your own fuel can minimize the chances of these substances making it into your engine, it’s better to be safe than sorry. This can be prevented with the use of a fuel/water separator, along with a fuel filter designed to screen out the smallest of particles that may be found in biodiesel.

Above: Diesel Power magazine’s project “Doomsday Diesel” is a study in how to build a vehicle that can reliably transport six people at least 1,000 miles during an emergency. In addition to lots of zombie-proof parts, it’s been equipped with a 12-valve Cummins, which is a mechanical engine that doesn’t rely on electronics to operate. To make sure Cummins can run on multiple source materials, the fuel is routed through a heavy-duty Nicktane water separator before travelling through a 2-micron Caterpillar fuel filter on its way to the engine.

Living With Biodiesel

Many people believe biodiesel works better with older diesel engine designs, but with the right preparations, even modern diesel engines can work reliably with biodiesel. The attraction of older designs is they require fewer, or even no electronic parts, and they only need to put biodiesel under a fraction of the 30,000 psi of pressure used in current diesels. The tradeoff is that newer diesels are much more powerful, run cleaner, and are more fuel efficient than ever before.

- Cleaning out your vehicle periodically is another way to reduce the risk of spreading germs.

Above: Whether you need a sedan that’s rated to get 43 miles per gallon, a truck that can pull a house off of its foundation, an SUV for off-road capability, or a van for secure cargo transportation, you can get one with a diesel engine. With diesels available in each vehicle category, you should be able to switch your family fleet over to diesel while meeting their vehicular needs. Plus, it shouldn’t be too hard to convince them to switch once you are making biodiesel that costs less than a dollar per gallon.

Diesel engines are also available in a wide range of vehicles, giving you the options of driving everything from a midsize car that gets more than 40 mpg to an off-road-ready SUV, a motorhome, or a pickup that can tow a gigantic fifth-wheel trailer. Biodiesel can also be used to cleanly power a generator to keep your home powered in an emergency, using the same fuel that runs your vehicles. So, if you decide to prepare with biodiesel, you’ll not only have a renewable fuel source that’s always at your disposal, you’ll also be ready for an emergency.

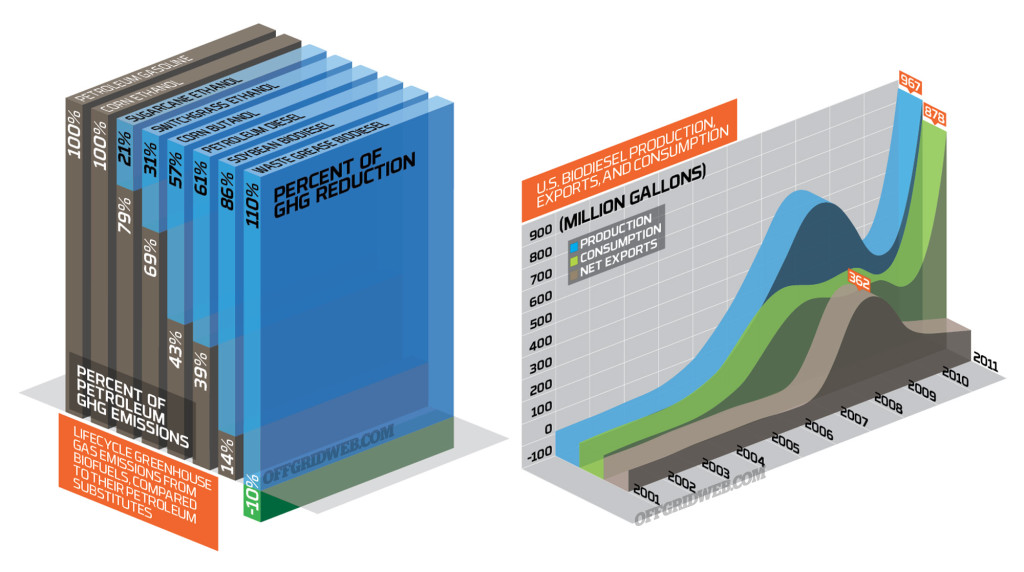

Above Left: Diesel engines may have a bad reputation for blowing smoke and polluting, but the Department of Energy has found that biodiesel burns much cleaner than petroleum diesel. (Data Source: Chapter 2.6 of the EPA’s Renewable Fuel Standard Program (RFS2) Regulatory Impact Analysis. February 2010. EPA-420-R-10-006.

Above Right: Biodiesel production rises when the economy drops, so making your own fuel can help insulate your family from the volatility of the markets. It can be stockpiled for later use, or sold for goods and services. You might say it’s good as gold, except the value of gold recently dropped, and biodiesel is still gaining popularity. (Data Source: EIA Monthly Energy Review, Table 10.4)