Before we dive into the Black Bunker BM8, lets review a little history. Humans have been developing handheld projectile weapons for a very long time, from the spear-throwers of the Paleolithic period to the gunpowder-loaded “hand cannons” which appeared in China around the 10th century. Air-powered projectile weapons are a newer development, but not as new as you might think.

They’re actually one of the oldest types of pneumatic technology. You can find the earliest known example of an air rifle, which dates back to the late 1500s, in a museum in Stockholm. In the 1700s, the Lewis and Clark expedition utilized a Girandoni repeating air rifle — a 10-pound, 4-foot-long, .46-caliber behemoth of an air rifle — on their 8,000-mile voyage across the North American continent. The Girandoni took about 1,500 individual pumps to fill up the reservoir with enough air to fire a 22-round magazine, but it didn’t require a supply of consumable and highly volatile gunpowder.

Above: Before the BM8 is locked into its functioning position, the front of the barrel and buttstock pivot to reduce its overall size for ease of storage and transportation.

These days, modern air rifles have powerplants much more efficient at pressurizing air, and there are several methods to accomplish this task:

- Spring Powered: Also known as a “springer,” this style uses a coil spring and pump piston to compress air in a chamber separate from the barrel. Typically, a user must use a cocking lever to pull the piston back, compressing the spring. Pulling the trigger releases the spring, pushing the pump piston forward, and generating the pressure needed to fire a pellet or BB.

- Pneumatic: Pneumatic air guns use air that’s been pressurized beforehand, either by pumping by hand, or by charging with an external source, which is then released in a controlled way to fire the round.

- Compressed Gas: This style of air gun works in a similar manner as pneumatics, except they make use of external, pre-charged gas cylinders, typically CO2.

- Gas Ram: Is an amalgamation between a springer and a pneumatic air gun. They need to be cocked like a springer, but the effort fills a gas chamber like a pneumatic.

Growing up, you may have taken out a soup can or two with your Red Ryder BB gun, but there have been some impressive strides in modern air gun technology. So, when we got our hands on one of the latest models, the Black Bunker BM8 Survival Air Rifle — a foldable, break-barrel, gas ram air gun — we were excited to take it for a test drive. Black Bunker let us take a look at both of their variations, the .177 caliber and the .22 caliber.

Above: The bayonet has integrated hex wrenches, oxygen tank wrench, and a bottle opener on the top.

Unfolding the Black Bunker BM8

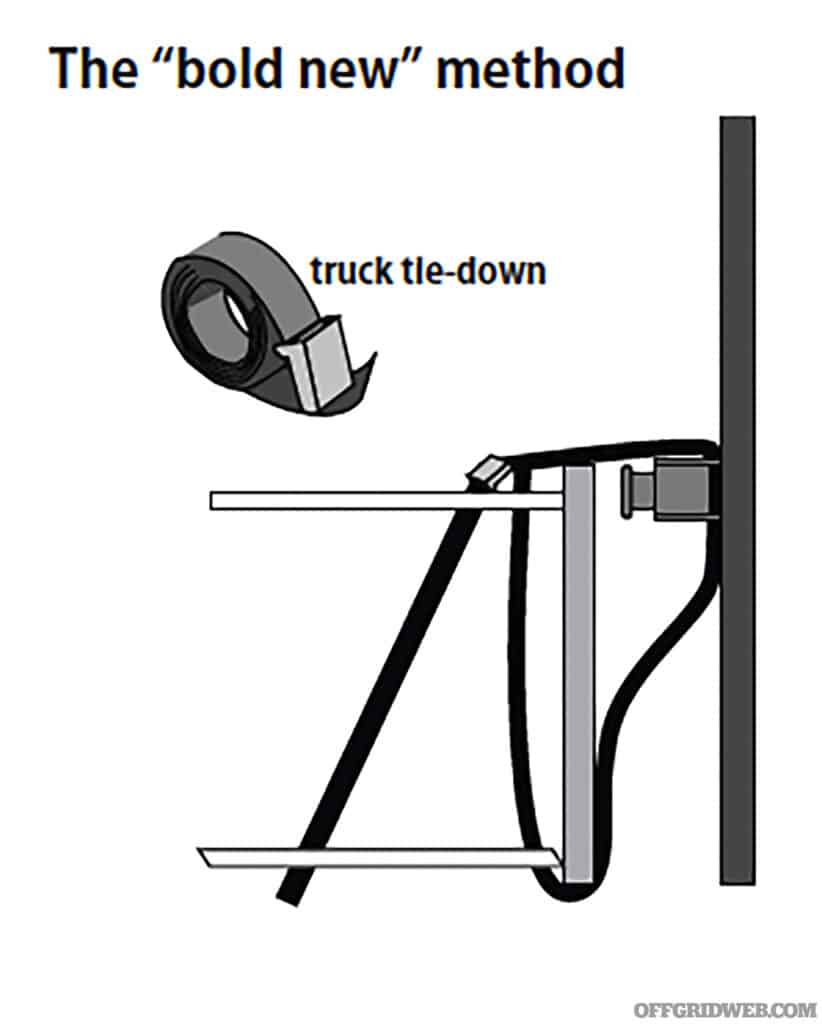

Looking at the triangular configuration of the BM8 definitely raises some eyebrows. There really isn’t anything quite like it. Broken down, the barrel and the buttstock fold around an odd-shaped carrying case, and lock into place with its cocking link arm. A simple metal release lever in the buttstock detaches the arm, and the three sections of the air gun pivot and snap firmly into place. There is no wiggle once fully assembled, giving it the feel of sturdy, one-piece gun.

Unfolded, it’s longer and a bit heavier than the traditional rifles you may be used to, but this is to be expected because the receiver houses a chamber strong enough to compress and store air. The feel of shouldering the BM8 is comfortable enough, and there are a few features worked into its design. For starters, it has three Picatinny rails — one on top to mount an optic, and two shorter rails on the side for accessories. At first, their placement seemed odd, but there is a good reason for it.

Above: The Black Bunker BM8 comes in two colors, can be fixed with a bayonet or silencer, and can be tuned to different Joules depending on which country it’s being sent to.

Because the BM8 is a break-action, the front third of the air gun has to be hinged down, both to charge the gas chamber, and to load the ammunition. If the accessory Pic rails were any farther forward, not only would they get jostled during operation, but any lights or lasers would have to temporarily aim away from the target. It comes with stock iron sights, which seemed a bit on the low side when I first aimed down the length of the barrel. There is a sweet spot for a cheek weld when using the irons, and it took a few repositions to find it.

To get the BM8 operational, the cocking link arm needs to be folded back toward the trigger, where there is a locking switch that holds it in place. Initially setting the switch to the “Unlock” position allows the link arm to fall into a dedicated groove; moving the switch to “Lock” keeps it there.

To charge the air gun, while holding the body of the rifle with your firing hand, the front of the barrel needs to be smacked downward with your other hand — this opens the breech to insert a pellet. Pulling the barrel further rearward engages the gas ram powerplant and charges the chamber with compressed air. It only takes a single pump to completely charge the air gun. The safety is a small lever in front of the trigger that gets flicked forward to fire.

Above: While folded in its storage configuration, the BM8 holds the included storage case securely in place.

For a conventional rifle shooter, charging the air gun is the most challenging task. Out of the box, it takes a decent amount of effort to break the action and pull the barrel back far enough to charge. There was so much resistance the first few times it was charged, I was worried I might break it. A few dozen charges later, it started to loosen up, and it became easier to perform this function. According to Black Bunker’s manual, the BM8 could have a break-in period of up to 250 rounds, which means it could take a few days at the range to get the action moving comfortably.

Breaking down and packing up the BM8 is relatively straightforward. Break the action and press a release button by the start of the buttstock to cause each third of the air gun to fold. It doesn’t require the storage case to be in the middle to connect it together. However, the case is uniquely designed to fit in that space, so why leave it out? If the case isn’t seated properly, the air gun will let you know by not clicking together securely. Once everything is in its storage configuration, the point where the handle of the case meets the buttstock is the best place to carry it around.

Above: Ammo for air guns is very inexpensive, even in bulk. Pellets come in different shapes depending on the desired application.

BM8 Specs

Black Bunker offers the BM8 in two calibers (.177 and .22) and two colors (Coyote Tan and Full Black). There are also several configurations to choose from beyond the stock model that include ½-inch UNF threading for a silencer, or a knife attachment — more on that feature later in this article — or a combination of the two. They also have several different series which cater to the laws of whichever region of the world they are being sent. For example, if it’s being sent to Germany, its calibrated to fire rounds at 7.5 Joules, Sweden gets 10, and the US of A gets 21 (for .177 cal) to 24 (for .22 cal) Joules.

Features:

- Picatinny optic rail and two accessory rails

- Adjustable rear sight

- Two-stage safety lock system

- Textured polymer buttstock

- Optional knife and bayonet attachment

- Water resistant case

Overall Length: 42.7 inches

Weight: 7.5 lbs

MSRP: $280

URL: black-bunker.com

Rounds Downrange

Before bringing it to the range, I needed some ammo. Sourcing pellets in the U.S. is easy and inexpensive compared even to .22LR ammo. A box of 1,250 rounds of .177 was $35, and a box of 500 rounds of .22 pellets was $10 on Amazon — less than $0.03 per round. Each of those boxes is about the same volume as my closed fist, which means I could plink away at targets for the foreseeable future without needing to worry too much about cost or storage. Using an air gun also means not having to consider the risks associated with combustibles like primers and gunpowder (as miniscule as those risks are).

Above: A bayonet can be attached to the BM8, if you’re into that sort of thing.

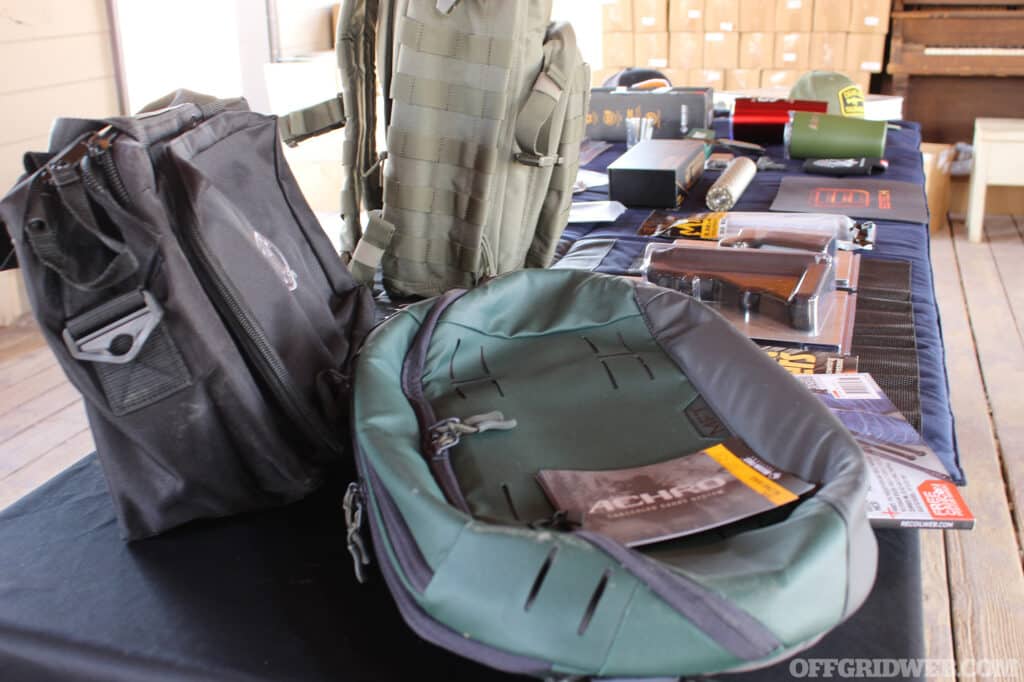

Difficult initial charging aside, my first real point of contention actually came from trying to pack the BM8 up for the range. Because I live in a densely populated urban area, walking around with what appears to be a folded gun — or even a gun in a case — may attract the wrong kind of attention.

With discretion in mind, I attempted to place the folded air gun into a backpack. Additionally, I was thinking that if transporting it this way would work, it would make for an interesting camping or bug-out gun. But the dream of walking to the range or the woods with my air gun discreetly concealed died as soon as it began. Because of the length and inflexibility of each section, it simply wouldn’t fit any of the packs I had lying around. Despite my best efforts to make it work, there was just no way it was going fit without sticking partially out of a zipper, or having to strap it to the outside, defeating the purpose. The most discreet container I could find that fit its odd shape was a large, blue IKEA shopping bag.

Above: Lights and lasers, like this Streamlight TLR RM-2, can be mounted to the side Pic rails.

Once I arrived at the range, I threw a Hawke red-dot sight on the .177 and left the .22 model with iron sights. As I got ready to cock and load the air gun, I experienced my second sticking point: occasionally, the cocking link arm on the .22 would loosen from its locked position just enough to prevent charging. In an effort to eliminate the possibility of operator error, I did everything I could to make sure it was properly seated in the “Locked” position.

It takes just the right amount of force to open the breech, and doing so while keeping the muzzle in a safe direction is trickier than it sounds. Think of it like jabbing a heavy bag — you want the point of impact to connect just at the surface and not much further, which requires holding and standing just right. Otherwise, you risk accidentally flagging someone as you move around grappling with the barrel.

Above: To charge the BM8, the cocking link arm needs to be folded back to the rear while in the “Unlocked” position.

Loading and charging seemed easier from a seated position versus standing. This was because I could anchor the buttstock in the bend of my hip, which made pulling the barrel downward less strenuous. Conversely, having to smack the action open was more challenging from seated compared to standing. Either way, this wasn’t the type of gun that was going to send pellets down range in rapid succession. It forces the user to focus on making every shot count rather than shooting more haphazardly.

Flicking the safety on and off, or away from and toward the trigger respectively, is a satisfying motion. The trigger itself is not in the realm of a performance trigger, as there was a noticeable amount of creep. Sending .177 down range hardly produced any amount of perceptible recoil, and the .22 was only slightly stronger.

Above: Pellets have to be loaded individually between each shot.

As far as accuracy is concerned, regardless of weather conditions, I would say the BM8 would hit any target within 50 yards consistently. Beyond that range, the wind really wreaks havoc on the trajectory of those tiny lead pellets. If the weather is calm, or you wait for a lull in any crosswind, ranges of 50 to 100 yards are more feasible but not guaranteed. With a dialed-in scope, it would probably make a pretty decent varmint slayer, but it certainly falls short of any kind of reliable defensive tool.

The BM8 did manage to draw a lot of attention to itself, as the combination of its unusual folding configuration and modern tactical looks is not something you see too often. It even got a few nearby shooters excitedly talking about wanting to pick up an air gun at some point in the future. One person made the comment, “It looks like something out of Call of Duty,” which elicited some amused laughter from a few passersby. But it seemed like the common reaction most people had was serious curiosity.

Final Thoughts

Let’s start with the elephant in the room: combining the break action with the powerplant makes for an interesting design, but also a challenge to charge and load. Although it did become progressively easier, the initial stages of the break-in are tough, even for someone with ample upper-body strength. For younger, lighter, or more physically challenged shooters, the BM8 is not going to be a great option.

Above: Charging the BM8 can be challenging while working through its break-in period. However, the fact that it only needs to be charged once to fire is a nice feature.

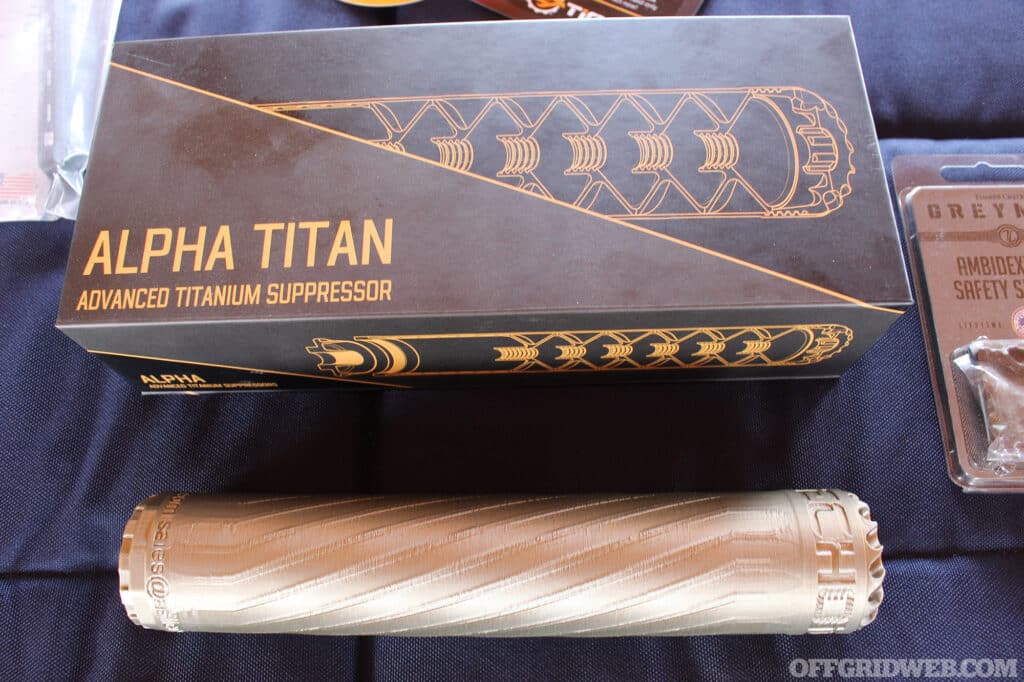

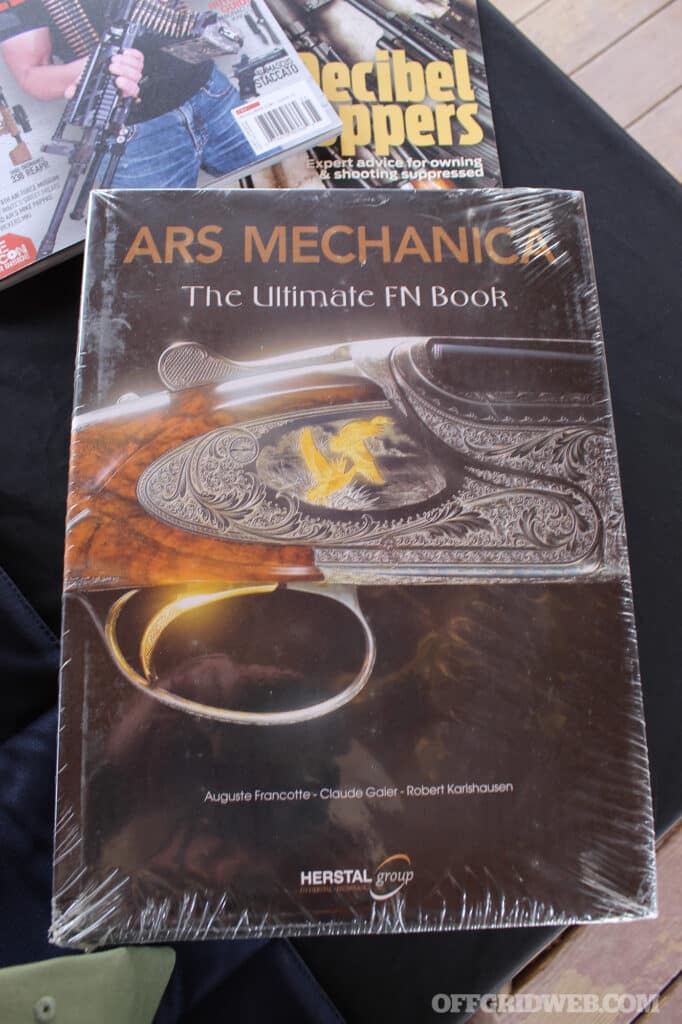

Strangely, Black Bunker offers an optional knife/bayonet attachment — this seems counterintuitive. One of the BM8’s biggest selling points is that it’s available in places where traditional firearms might be hard to get; Black Bunker even detunes the rifle’s power on a country-to-country basis to stay within legal limits. With a bayonet attached, it’s not hard to imagine pearl-clutching politicians and activists labeling it as a “tactical assault airgun” or some equally stupid moniker. I’d much rather have a fixed survival blade that accompanies the carrying case, as opposed to an impractical bayonet attachment I’ll never affix.

Speaking of the carrying case, I do think this is a useful accessory. Not only does it fit nicely within the collapsed configuration, but it easily stores all the ammo you would ever need for a day of shooting, plus room for basic maintenance tools. Black Bunker recommends using it as a survival kit, which is a great idea, and the whole setup could be a nice addition to an overlanding rig or long-term campsite.

Above: Firing the BM8 offers an enjoyable experience at a budget friendly cost.

Picatinny rails are a nice touch, but the side rail location is so far back that you’re bound to get some shadow from the barrel if you mount a light to it. This isn’t really a deal-breaker since you wouldn’t want to do any CQB with the BM8 anyway. Mounting an optic is an improvement over the basic iron sights, and the top Pic rail has plenty of space for whatever optic you decide to go with. One consideration, though: if you mount a scope, and the air gun is folded into thirds, that scope is directly on the bottom, and you need to be careful when setting it down.

Not having to worry about carrying along a bunch of CO2 cartridges works in the air gun’s favor, making it a truly self-reliant survival gun. Combine the low MSRP and low cost of ammo with its modern looks and its ability to fold up for easy carrying and transport, and the BM8 makes for a unique air gun with a lot of potential for utility and fun.

READ MORE

Subscribe to Recoil Offgrid’s free newsletter for more content like this.

- Ruger Mark IV 22/45: Review and Upgrades

- Symtac Shotgun Class Review: Don’t Fear the Recoil

- New: Hatsan Invader PCP Semi-Auto Airgun

- Comparing the .22 Caliber SIG Sauer ASP20 and Benjamin Vaporizer Airguns

Editor’s Note: This article has been modified from its original print version for the web.