In This Article

It doesn’t really snow here.” This is a statement you’ll often hear from residents of the more temperate areas of the country. Through previous experiences, they’ve been conditioned to expect a typical range of seasonal weather conditions. Occasionally, there may be a heat wave or cold snap that pushes temperatures slightly outside the norm, but these events rarely do more than make locals a bit uncomfortable for a few days.

At worst, there might be a dusting of snow in the deep of winter on rare occasions, leading to traffic jams and school closures, but it fades away quickly, and life goes on. This cycle can lead to a condition psychologists call normalcy bias — the tendency to expect that events will always happen the way they’ve happened in the past. Normalcy bias is one of the greatest enemies of preparedness, since it causes us to underestimate the likelihood and destructive power of a disaster that doesn’t fall in line with previously observed historical patterns.

For one example of this phenomenon in action, look no further than the Great Texas Freeze of February 2021. The National Weather Service described it as a “brutal and enduring cold that enveloped the entire state of Texas,” and it marked the coldest winter storm since 1989 — far enough in the past that many Texans had no memory of a winter so harsh.

With nearly nine days of freezing temperatures throughout much of the state, it was also the longest freezing streak in Texas’ recorded history. The impact was disastrous. A total of 246 deaths were attributed to the storm, the majority of which were a result of hypothermia. Power outages affected nearly 10 million people. Grocery store shelves were picked bare.

Iced roads became impassable in cities and caused fatal pileups on highways. Pipes burst in homes and municipal infrastructure, causing many counties to advise residents to boil their water before drinking it. More than $1 billion in damages were caused by the Great Freeze.

So, how can you prepare for a deep freeze of this magnitude if you live in an area where it’s practically unheard of? Even if your household is ready, will you be able to cope with the widespread impact of infrastructure and roads shutting down for weeks? We asked cold weather survival instructor Jerry Saunders and search-and-rescue training officer Patrick Diedrich to share their thoughts on how to approach this chilling scenario.

The Scenario

- Situation Type: Unexpected deep freeze

- Your Crew: Yourself, your wife, two children (ages 2 and 6), and your mother-in-law (age 77)

- Location: Southern Arizona

- Season: Winter

- Weather: Snow and freezing rain, high 25 degrees F, low 3 degrees F

Above: Areas that rarely get snow lack snowplows and road treatment procedures. Combine this with motorists who aren’t used to driving on ice, and it’s a recipe for dangerous roadways.

The Setup

Your family lives in Sahuarita, Arizona, about 30 minutes south of downtown Tucson. You’ve resided here your entire life, and your wife grew up in Florida, so neither one of you has much experience dealing with cold weather. You have two kids — a toddler and a 6-year-old — as well as your wife’s elderly mother, Lynn, living at the house. Lynn has had chronic health problems recently, so she takes several medications and needs help with daily tasks. As a result of caring for her and the kids, your wife hasn’t been able to work, and money has been especially tight lately.

The Complication

About a week ago, news stations started talking about an incoming weather system that could lead to heavy snow and freezing temperatures throughout much of southern Arizona. They say it could be worse than anything the state has experienced in more than 100 years. You initially rolled your eyes at the sensational headlines and round-the-clock Winter Apocalypse 2024 coverage, but the seriousness of the situation became clear as freezing rain began to fall.

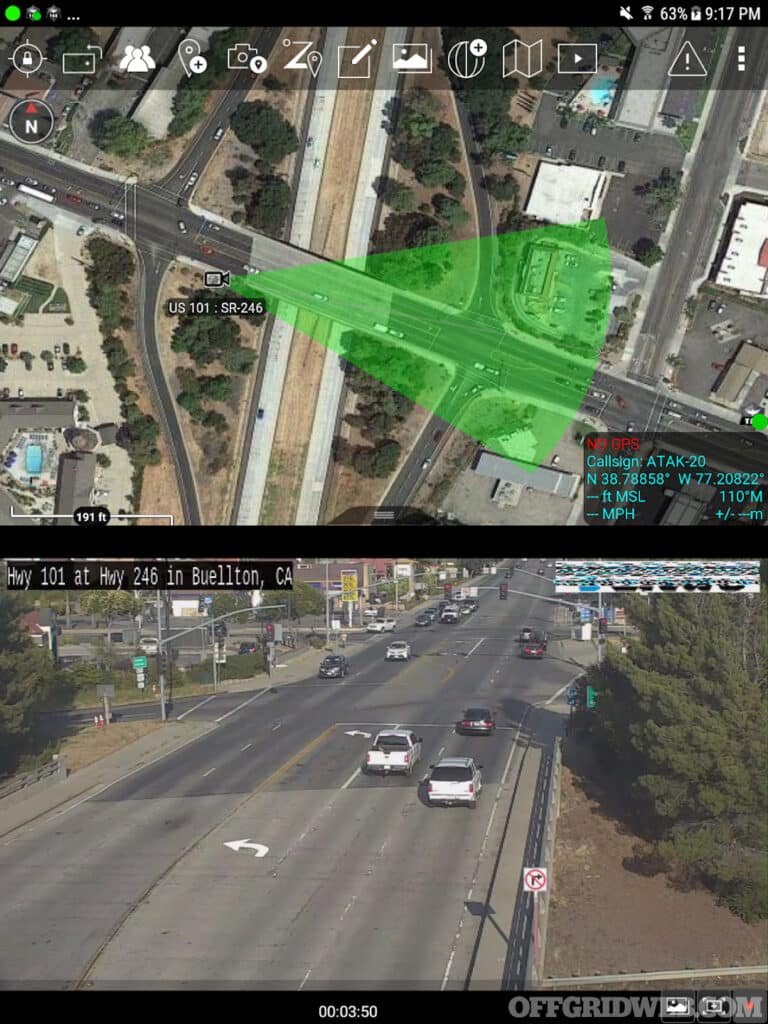

Ice has coated every building, vehicle, and roadway. Dozen-car pileups have become a daily occurrence on local interstates, and your neighbor couldn’t even get his truck out of his driveway. If you could make it to the grocery store, there wouldn’t be much left to buy — videos on social media show panicked shoppers rushing through bare aisles. The time to stock up has already passed.

Yesterday, the power went out. The utility company says it may be several days before it’s fixed. The local cellular network also seems to be down because of the power outage. Your home isn’t plumbed for natural gas; it relies on an electric heater and electric appliances, so you’re going to have to find another way to stay warm and cook food. You’re worried about the kids, since they don’t have much cold-weather clothing, and your wife is even more worried about her mom.

She’s starting to run low on medications and you’re not sure how you’ll be able to get to a pharmacy for a refill. This morning, you noticed you have no running water. You’re unsure if it’s affecting the whole neighborhood or if the pipes in your home have frozen; if it’s the latter, you’ll need to ensure the pipes don’t burst and flood your home when they thaw.

How will you deal with all these challenges related to the plummeting temperatures? What can you do to keep your family healthy during this deep freeze, and protect your home from costly damage? If you need to venture out for medication refills and other supplies, how can you do so safely?

Above: A portable propane heater can be worth its weight in gold if the power goes out during a winter storm. Just make sure to use them in large, well-ventilated areas. (Photo courtesy of Mr. Heater)

Cold Weather Survival Specialist Jerry Saunders’s Approach

Preparation:

Living in a hot climate like Arizona, such an acute cold weather event might seem like a hoax or sensationalized news. You might try to rationalize it as “just another bad call by the weatherman” or take the “we’re too evolved to freeze” approach. Even sensationalized news usually holds a thread of truth. A phrase I use often is, “everything exists on a sliding scale.”

Improving something such as cold weather knowledge and preparations in an arid climate might seem absurd, but in learning to live in an extremely cold place, I’ve found some of the best survival skills are those of the tradesmen and women. Plumbing, heating, electrical, and construction all correlate to water, fire, food, and shelter.

Preparing for any low-occurrence disaster on a residential structure ideally would be more of a long game than a knee-jerk reaction. Some people would jump at the chance to do an extreme cold weather survival course, even pay quite a bit of money to learn the nuisances of existing in cold weather. But if you’re trying to be a well-rounded and self-reliant person, or your goal is to lessen the effects of this type of natural disaster, consider the following.

Most of the population occupies a dwelling that has water pipes in it, but if you cannot fix it yourself then you’re at the mercy of someone else who can. Also, the trades are in a steep decline. U.S. plumbing industry stats for 2023 state that 55 percent of contractors need a plumber to finish a job right now. That’s an indicator that your repair time on your burst water pipe will be long after your house starts to look like a petri dish.

After a free 3-ish hour class at Home Depot, I learned how to winterize a house, lag pipes, braze copper, fix breaks, and cut and crimp PEX. PEX, in some cases, is a better option for cold environments because of its ability to flex and expand, but it should be avoided if your place is prone to rodent infestations and should not be installed in locations with direct sunlight.

A solid way of preparing in advance for a cold weather event is to take classes that allow you to understand your home and the tools used to make minor to moderate repairs. Hands-on classes are preferred. I also have a small collection of books from the thrift store on electrical, plumbing, and general repair. Don’t count out the family as a good education source. You could also use online resources for those late-night deep dives, and TV shows like Ask This Old House have lots of tips for people looking to learn. All are good options, but books still work in the dark.

Focus on general repair techniques for the exterior of the structure, plumbing, and electrical. These will allow you to understand, prevent, and make repairs that could otherwise spiral out of control.

Much like your EDC pocket tools having multiple functions, your home preps should also be multifunctional. For example, one prep for the cold could be to add a “pigtail” to your house. This should be done by an electrician, but it allows you to safely hook up a portable generator outdoors to your house’s power grid. Blackouts are just as prone to happen in the summer as they are in the winter. This one addition can make your house more prepared all-year round.

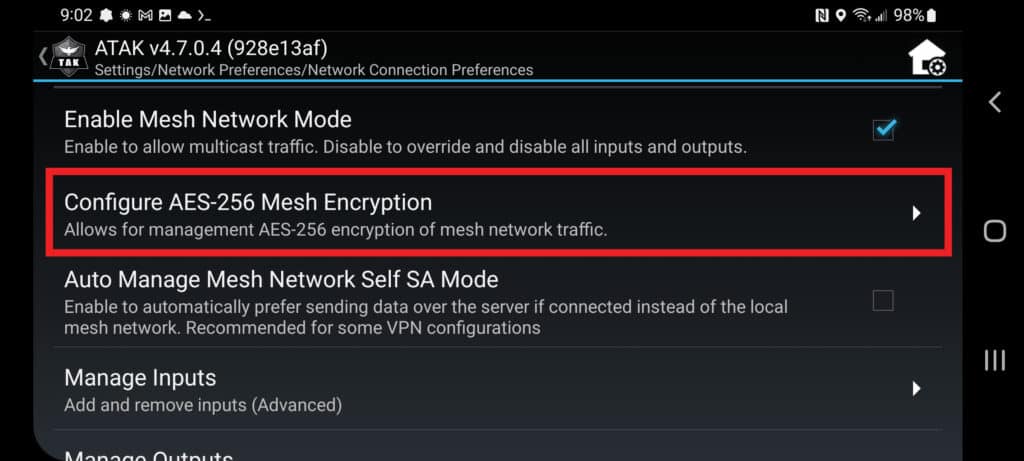

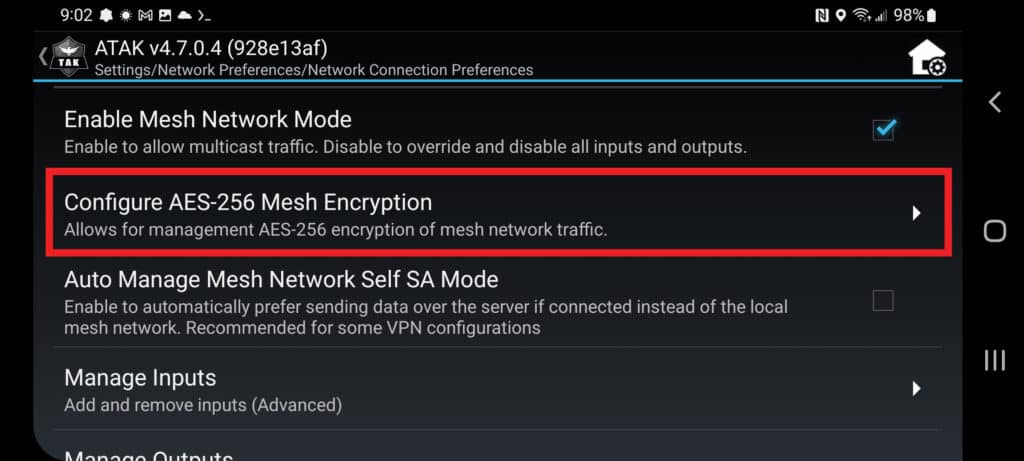

Another item I have on hand is a Mr. Heater Big Buddy propane heater. It’s small enough to easily store in the closet and runs on those little green propane cylinders you see in the camping section. The addition of a small hose allows you to attach it to a 20-pound tank like you might find by your outdoor grill. A 20-pound tank will boost the burn time to 24 hours on high or a whopping 108 hours on low. On its high setting, the Big Buddy will efficiently heat a 20 by 20 room.

Above: Winter storms are rare in many parts of the United States, and this rarity can lead to complacency. No matter where you live, you should consider how prepared you are for extreme weather events.

On-Site:

Determining the severity of a pending natural disaster is nearly impossible on an individual level. This can make the news and weather station a necessary evil for things like cold front timelines, closures, shelters, and other emergency information. But this information is important for last-minute preparations. The cliche bread, eggs, and milk grocery store run as the flakes are falling rewards the unprepared with nothing but empty shelves, long lines, and an elevated risk of a motor vehicle crash.

Upon first hearing about the storm, I would take what available gas cans I own and top them off, mix fresh two-stroke fuel for my chainsaw, and fill up any equipment that needs it. I might also pick up some Heet (yellow bottle) in the automotive section. This stuff is a high-grade alcohol that’s antifreeze for gas but it’s popular amongst hikers as alcohol stove fuel. This is a good time to pick up an extra propane tank or two also.

I would want to have an axe on hand, preferably a splitting maul, but in Arizona you may only find a normal axe. Get one with fat cheeks for the best splitting capability. As soon as you hear any notifications of a pending natural disaster, if you have someone under medical care in your home, call their doctor and request a three months’ supply of their meds. If this isn’t possible, get what you can. On your drive home, note locations of drug stores closer to your house in the event you need to walk.

Maintain a reasonable supply of freeze-dried meals. These are unaffected by temperature and have a long shelf life. Keep several Jerry cans for water. Ensuring these are clean and filling them before the storm will ensure you’ve got plenty of water for a few days. Supplement these preps with dry goods like rice, noodles, and beans. Also, if you are experiencing a freeze for the first time, welcome to “your garage doubles as your freezer” season.

My emergency bin contains about 20 emergency candles that last 24 hours apiece. I have a few backup cooking stoves in there, including an MSR XGK : stove that can run on almost any fuel. I also have an Anker power pack that will charge my iPhone almost seven times. Complemented with an assortment of headlamps and lanterns, this box keeps me lit. As for spare batteries, lithium will be a better choice than alkaline due to its enhanced cold resistance.

As far as family goes, it’s important to sit down and talk things out. Have the kids play “dress up” to find all their warmest clothes and start preparing for a campout together in the living room. The 6-year-old can act as Grandma Lynn’s “doctor” and help with small tasks like getting water and tissues and such.

To prepare the house, I must refer to my favorite motto on the homestead, “caulk and paint till it is what it ain’t.” Work in a top-down fashion. Clean the roof and gutters if applicable. If you have dirty gutters, snow and ice will back up and peel your roof back like a tin can. Clear any leaves off the porch or anywhere you may need to clear snow and ice. Once wet, leaves freeze; it’s like concrete trying to remove them.

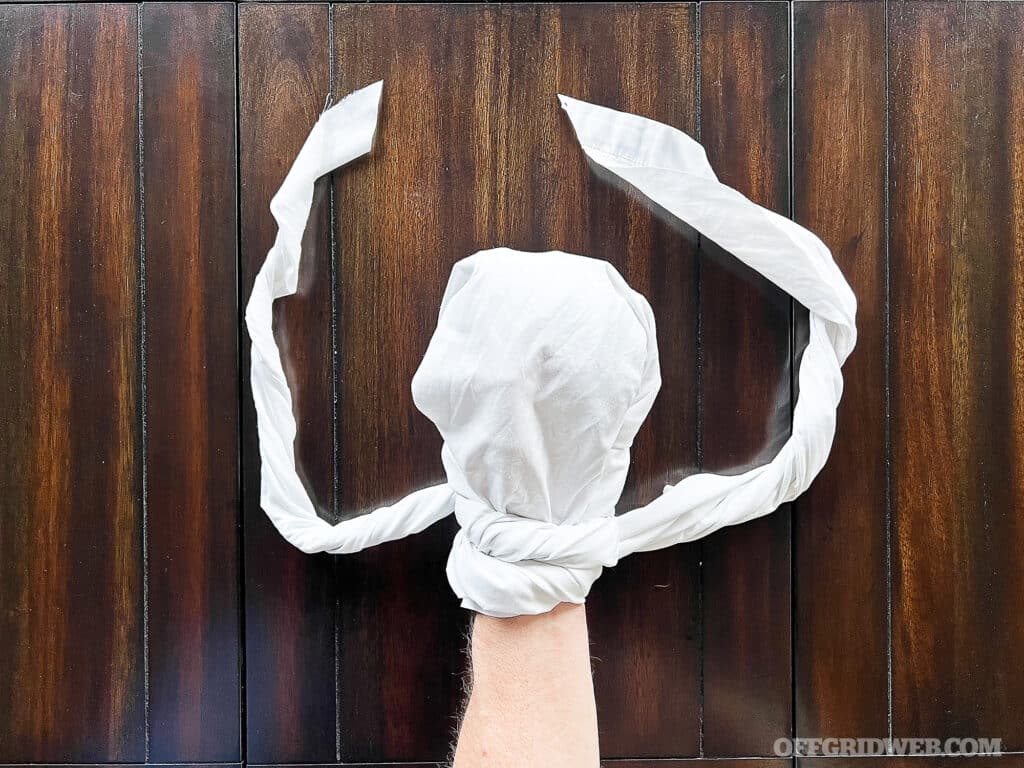

The foam gap filler Great Stuff is ideal for gaps around 1-inch thick. Turn off outside water taps and wrap a towel around them, then cover them with a plastic bag and duct tape. If you have a sprinkler system in the yard, disconnect it and try to blow it out with pressurized air. Sprinkle cat litter on the porch or high-traffic areas to add some grit to the ice. Cover any wood supply you may have.

Everyone should be gathering blankets and warm clothes in the living room. Rearranging the space for everyone to sleep and care for Lynn. To make a DIY window insulation kit, grab painter’s plastic and a couple of rolls of duct tape. This will allow you to put a tight cover on drafty windows and doors but still reap the benefits of solar radiation. There are real kits sold online for about 5 bucks, but you might want to have those well in advance.

I’d pour a little bit of that Heet in my vehicle’s washer fluid to keep it from freezing solid. RainX makes a cold weather washer booster you might find at some truck stops. Never try to clear ice with your windshield wipers. This will only succeed in gouging the silicone on the wiper blade. Truck stops sometimes stock hard-to-find items because truckers take high mountain winter routes.

While parked, I lift my windshield wipers so that they don’t freeze to the window. Many people down south like to run 100 percent water in radiators, so this needs to be drained at least partially. I have a CB radio in my truck that allows me to talk to truckers. This can be the best real-time news method for things like traffic jams and vehicle accidents when you’re near a highway.

Above: Layer up to stave off the cold but be cautious if you’re exerting yourself. Sweat-soaked base layers (especially cotton) can cause your core temperature to drop quickly and lead to hypothermia.

Crisis:

Expect the power to go out. We always have a hallway light on, and I know if it’s out, the power went. Kill the breaker to anything important to keep power surges from damaging them. Turn on faucets slightly to allow slow movement. Open any closets or cabinets to allow the smaller spaces containing pipes to stay above freezing.

Check on everyone at night, inspecting their faces, hands, and feet for frostbite. If grandma is OK and the kids are bundled, get them outside occasionally. Getting outside even if it’s cold will lessen the effects of cabin fever, and make the inside seem that much warmer when they return.

Cooking in the cold usually takes a lot of water. Use large pots to melt the snow outside by a fire and then add it to a reservoir inside. Pull from this reservoir to cook freeze-dried meals and dry goods. Save the water in the Jerry cans for drinking. Large rocks and bricks can be warmed by this fire and taken inside to capture their radiant heat. Place these on a surface capable of such hot items.

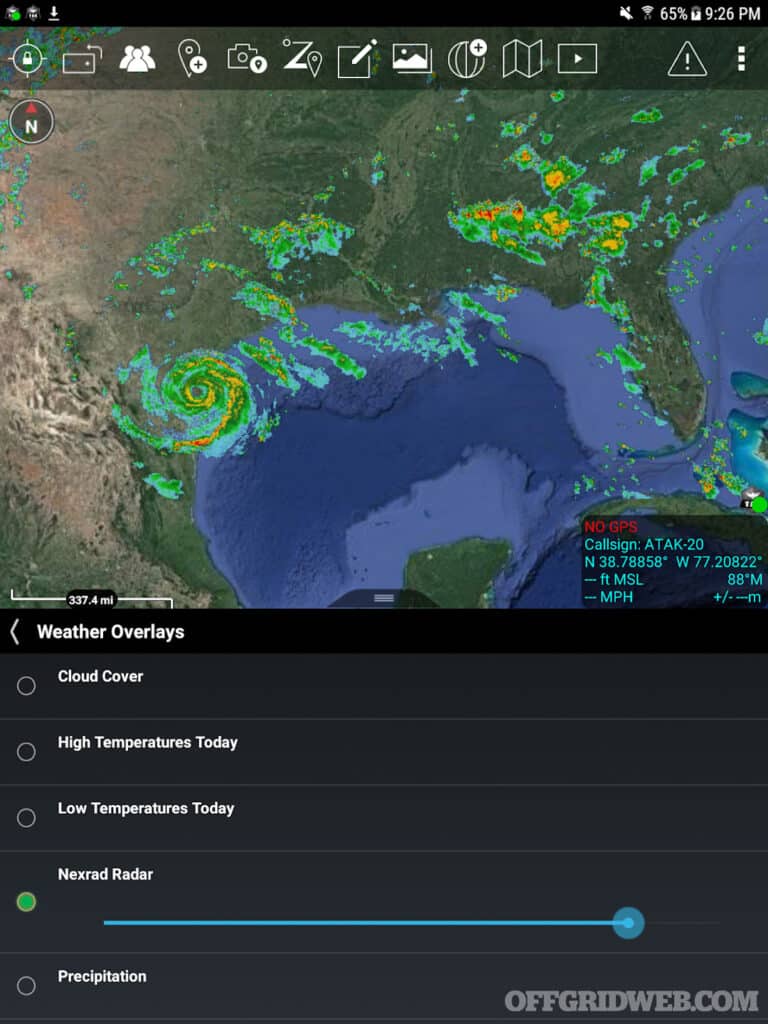

A weather radio can pick up important weather and emergency information. If you’re far enough into a disaster, the Red Cross may show up and start handing out hand-crank, portable AM/FM radios for informational purposes.

If I know my water is going to go out, fill the tub with water then shut it off. This is more water I don’t have to make from snow. This can be used for hygiene needs or boiled for cooking. If you find a frozen pipe in your house, you can rewarm it by wrapping it in a towel and slowly pouring hot water over it. Once water is restored, there can be a lot of questions about the safety of the water. You can find several test kits online between 20 and 30 bucks.

Keeping kids entertained can be a full-time job. Grandma Lynn is elderly, but if she’s still lucid she can spend time with the kids and the kids can help take care of her. Every couple of days, trade out the toys and books in the “warm room” for some new ones to keep it fresh. And like I said before, get the kids outside. Teach them what winter is and that it isn’t all bad.

It’s important to get some time alone with your wife during these times. She’s working hard indoors, and you’re working hard outdoors. You’re both working toward the same goal but doing it somewhat alone. By coming together at the end of the night and talking or going for a cold walk, it allows you to rekindle and remain resilient in hard times.

Final Thoughts:

Looking back, we know a lot of what was lost in Texas was blamed on the inability to get gasoline. I’m still reading articles that claim that, as of 2023, the gas problem, despite throwing $50 million at it, is still not solved.

I’m sure, given the extremes of our weather patterns, we’ll see freezing temps in abnormal places again. Taking some educational steps along with adding a few pieces of seemingly unnecessary winter items could make a big difference for your household.

SAR Training Officer Patrick Diedrich’s Approach

Preparation:

News these days is overly hyperbolic, carefully crafted to capitalize on the reaction to stressful situations. Storms are named, tracked, and given terrifying personas to keep our attention glued to a screen. So, when the weather forecasters started calling the latest incoming storm front Winter Apocalypse 2024, most of us brushed it off as another attempt at sensationalism and went about our day as normal.

Arizona does see days below freezing in the winters, but not much farther than that. It may surprise people living in the north, but we do have warm clothes and jackets here. When the temperature drops from 110 during the day to 70 after sunset, a 40-degree change, it does feel quite cold respectively. Snowfall in Tucson isn’t unheard of, and it’s very common in the mountains to the northeast. Puffy jackets, hats, and gloves are in most people’s coat closets. But beyond that we do not have much of the gear, tools, or supplies to deal with copious amounts of ice or snow.

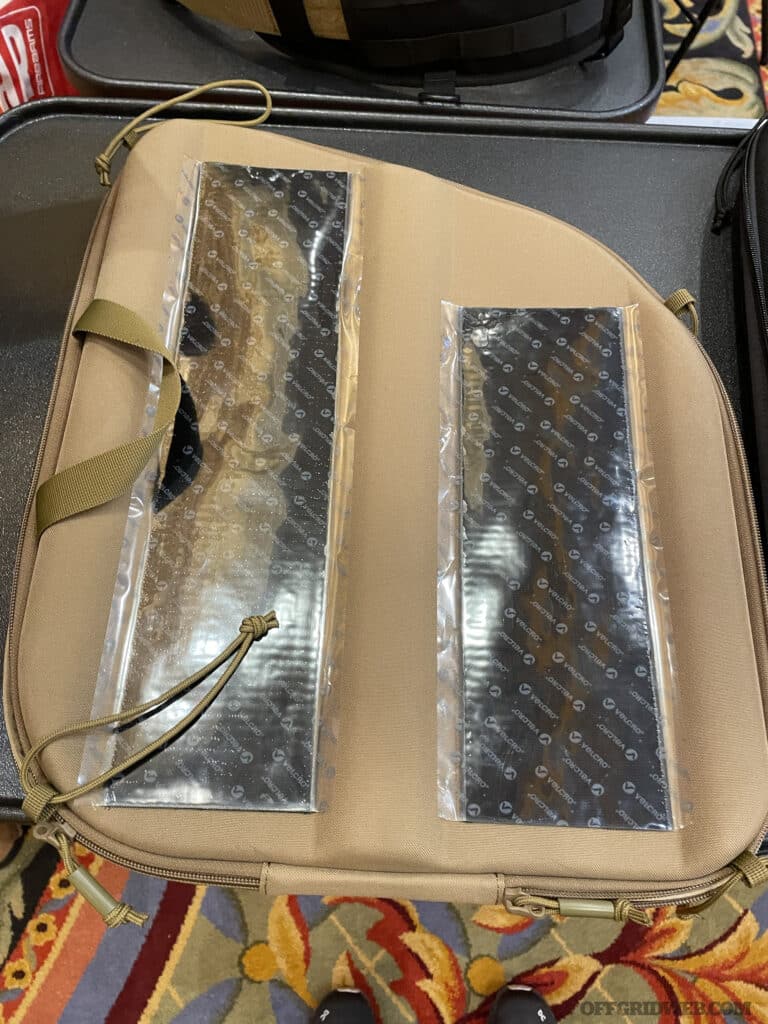

Weather reports became increasingly foreboding, and with some not-so-gentle prodding from my wife and her mother, Lynn, we decided to take a few precautionary measures. Following advice on the Arizona Department of Transportation (ADOT) website, we topped off the fuel in our vehicles and installed the snow chains we typically only use in higher elevations. We also built a vehicle emergency kit with first aid supplies, flashlights, snacks, and some water. But we added a few winter extras, like warm blankets, a box of kitty litter, a small folding shovel, and an ice scraper.

For the house, we took stock of our food and water situation. Before the storm, we headed to the store to make sure our fridge is full and that our shelves have a few extra days’ worth of non-perishable items. We picked up several cases of bottled water and called in any medications eligible for a refill. Unfortunately, we’re not the only ones making last-minute preparations, and some of the food items we were forced to choose from aren’t terribly appetizing. We picked up some extra flashlight batteries, a deck of cards, and a few coloring books for the kids, just in case the power goes out.

We overheard someone in the store talking about a deep freeze they experienced in Georgia a few years back, and how the water in the pipes froze, burst, and caused serious damage. After listening to that story, we headed to the hardware store to find some heat tape — a long heating strip that uses electricity to warm up pipes and keep the cold from causing damage. However, we were too late, and they were all out of stock. They did have a few extra NOAA weather radios available. After discussing possibility of being without a heat source, we headed to the nearest camping supply store to pick up a few propane tent heaters and several bottles of extra propane.

Upon returning home, we dug out every piece of cold weather clothing we could scrounge up and began managing the emotions of the two kids. Instead of turning it into a fear-based scenario, we talked about how we might be doing some “Christmas camping” in the house, and to not be frightened if the electricity suddenly cuts out. To put everyone’s mind at ease, we rehearsed the scenario by turning off all the lights and electronics and practiced finding flashlights and meeting in the same place.

We checked on our next-door neighbors, but they didn’t seem overly concerned, and after some small talk, we found out that they’ve made no preparations. They even seemed slightly amused at the few small steps we took just in case the worst happens. When we brought up the not-so-distant winter storm that happened in Texas a few years back, they shrugged it off and returned to their evening entertainment. Back home, I voiced my own doubts about the steps we’ve taken, but my mother-in-law, having lived through more than one dangerous cold weather event, says we’re doing the right thing.

Above: For adults, a winter storm may be an inconvenience, but don’t let it make your whole family miserable. Spending a little time playing outside — as long as you can stay warm and dry — can lift everyone’s spirits.

On-Site:

That night, the news began warning that we should brace for the impact of the storm, and that it may be worse than originally reported. Checking outside, we saw that it was beginning to rain and the wind was picking up. Even so, we kept a positive attitude, changed what we were watching to something a little more uplifting, and went about the rest of the evening as we normally would. Later, we put the kids to bed and settled in for the night, assuming that the storm would pass us by without any issue.

Our sleep is interrupted as the background hum of electricity cuts out, replaced with deep silence. The house is pitch black, and the only sound is that of ice pelting the windows and the wind howling over the roof and through cracks in the poorly sealed windows and doors. Grabbing some flashlights, we go to check on everyone.

The kids are sleeping soundly through the event, so we make sure they’re bundled up warmly in their blankets and do the same to Lynn. Outside, it looks like there is a glossy sheen covering everything in sight, the entire landscape glazed in a frozen layer of ice. Broken tree limbs scatter the ground, and there is clear indication of powerlines fallen to the earth from the weight of the ice coating.

Using some painter’s tape, we try to seal the spots around the windows and doors where the frozen wind is trying to force its way through. When we run out of painter’s tape, we use an almost spent roll of duct tape. When we run out of that, we shove some towels in the large gaps beneath the doors. Even with the major drafts sealed off, the temperature inside is steadily plummeting.

Worried about the cold, we get the propane camping heaters up and running near the base of the kitchen sink, thinking we can stay warm while simultaneously keeping the water pipes from freezing. Unsure of what to do next, we turn on the NOAA weather radio.

When the radio comes to life, we’re bombarded with updates on rates of precipitation, wind speeds, storm location and other pertinent information. It sounds like the storm will go on until at least noon the following day. As the information begins to repeat itself, we scan through other channels, and it is fortunate for us that we did. On one channel, a reporter is warning the audience about the dangers of burning combustibles inside the house.

Apparently, some people who owned a gasoline-powered generator have already succumbed to carbon monoxide poisoning. Although we’re not creating as much exhaust as a gasoline generator, we still turn off the heaters and discuss how we could provide adequate ventilation.

Crisis:

It’s not long before the chill permeates the entire house and becomes uncomfortable enough to wake up Lynn and the kids. They see the flashlights in the kitchen and wander in groggy, cold, and confused. To stay warm, we don our winter outerwear and huddle together on the couch beneath as many warm comforters as we can gather. Some of us manage to catch a few winks, but as morning light finds its way through the continuing storm, it’s apparent that none of us are well rested.

With the electricity out, breakfast is cold cereal, which does nothing to boost morale. Lynn attempts to get a glass of water but nothing flows from the faucet. Feeling thirsty, one of the kids tries to grab a bottle of water, but it flash freezes solid due to a phenomenon called supercooling. All the water bottles are affected by this, and we endeavor to find a way to warm them up. I try to warm one against my body, but I am already feeling a little too cold, and a bottle of ice is just too much to deal with on top of it.

Realizing we need to start using our propane camp heaters, but safely, we crack a window for fresh air and point the heaters in the direction of cases of water. Soon we’re all huddled miserably around the heaters and water. The cold is tremendous, not something any of us have ever experienced, and it seems like everyone is rattling with shivers, becoming physically and emotionally withdrawn.

Maybe there’s a better solution. Perhaps we can warm up in our vehicles. Perhaps we can drive around, find a hotel or restaurant that still has power, and warm up more efficiently. That must be better than struggling to find warmth around a tiny heater.

I grab my keys and attempt to open the front door, but it doesn’t budge. The ice must have caked around the edges of the door, sealing us inside the house. With a more vigorous push, with my body weight behind my shoulder, the ice breaks, and the door swings open. As soon as my foot hits the stoop outside the door, I slip and land with a grunt on my back. Freezing rain is still coming down hard. Everything is coated with ice, and none of us have the footwear to find adequate purchase on its surface. Going to the garage, I find an iron garden rake, and begin scratching and breaking the surface of the ice to clear a way to the car.

The car is entirely coated in a glaze of ice, as is everything. Cautiously, I tap the edge of the rake around the outline of the driver’s side door, weakening the ice just enough to be able to open it. Sitting in the driver’s seat, and out of the freezing rain, I realize that my puffy jacket does nothing to stop the wind or keep water from permeating the material. I’m completely soaked and feel cold down to my bones. I struggle to find the physical coordination to get the key in the ignition, but I manage to do so. Turning the key, the engine sluggishly turns over a few times but doesn’t start. Dejected, I rest my forehead on the steering wheel and pray to all the gods for the car to start.

I turn the key again. Nothing.

Again. Nothing.

One more time. The engine miraculously roars to life, and I heave a sigh of relief as I turn up all the heat settings to the max. Now it’s time to get the rest of the family out here.

First is my elderly mother-in-law. My wife and I walk her to the car carefully, so she doesn’t slip and get hurt. Next are the kids, who are so miserably cold, they walk to the car in a shivering daze. I notice my neighbor carefully sliding his way across the driveway to my location.

He explains that they didn’t go shopping, they’re almost out of food and wondering if we had any to spare. I give him what’s left of the cereal, a few cans of potted meat, and suggest he follows us as we look for a warmer location. But he has no snow chains for his tires, and a quick glance down the road reveals a chaotic scene. Numerous vehicles are stranded in ditches or crashed into trees, suggesting driving without chains is a terrible idea.

Grabbing my phone, I attempt to open my mapping, but the signal reads “SOS.” Seems like the cellular towers have also been affected. Instead, I turn on the radio in the car in hopes of finding some information about what might be happening. Most of the FM stations are nothing but static, but one of the AM stations appears to be working still.

The broadcaster states that FEMA is recommending everyone shelter in place, since it is not safe to be traveling. Reluctantly, we wait out the rest of the storm, parked in the driveway in the warmth of the car, sipping water from slowly thawing bottles.

Eventually, the storm dissipates, the sun breaks through the clouds, and the ice begins to melt. But we’re not out of the woods yet. Several pipes in our house have expanded and split open in the cold, and we must turn off our water main until they can be repaired.

In the back yard, frost heave has moved the earth in such a way that the septic line to our drain field has ruptured, and now whenever a toilet is flushed, raw sewage bubbles to the surface in our back yard. And our situation is just a microcosm of what has happened to the entire region affected by the storm. It will be weeks, if not months, before everyone has working septic and water, not to mention power and internet connectivity.

Final Thoughts:

Even though we thought we were prepared by being proactive and gathering supplies before the storm, inexperience with disasters, and with cold weather conditions, could’ve led to fatal results. Things like a 5-gallon bucket with a toilet lid, a safely installed backup generator, and alternative ways of preparing food would ensure that our family and neighbors could be taken care of over the duration of the disaster.

Installing a car battery with enough cold cranking amps would keep our vehicle running when the temperature plummets. Understanding how to layer clothes properly, or how to improvise a rain shell could’ve prevented a potentially hypothermic situation. Even footwear like cleats or crampons would have been incredibly useful to stay mobile as the ice accumulated.

Conclusion

Living someplace that’s usually hot doesn’t mean we should ignore the cold entirely. Although uncommon, storms like these have occurred in the past. January 1913 was the coldest winter on record in Arizona, with temperatures down to 6 degrees, and that was a time when most Americans were much more comfortable with self-reliance and living through hardships than they are today. Back then, when things got tough, you figured it out on your own or asked your neighbors. More than a century later, we’ve grown accustomed to finding solutions to problems with the aid of a smartphone and internet connection, and this complacency can be dangerous.

Although we should be prepared for outlier weather events, it’s important to keep them in perspective. In southern Arizona, there probably isn’t a great need for a garage full of snowmobiles and firewood, but reviewing a little bit of winter preparedness before the season starts could save lives during inclement weather.

This mindset applies to all climates and seasons — if you live in an area where snow and ice are common, perhaps it’s time to consider how prepared you are for a prolonged heat wave. If your area is frequently affected by heavy rainfall and flooding, you should plan for a drought. Mother Nature is a fickle mistress. Don’t let her catch you off guard.

Meet Our Panel

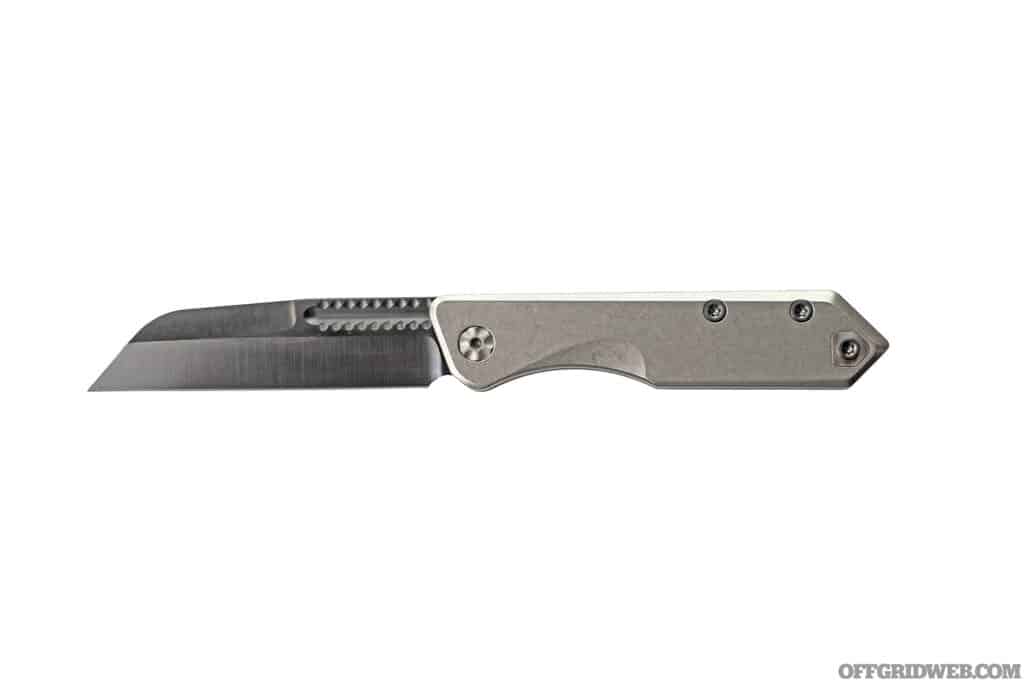

Patrick Diedrich is a seasoned survival expert with over 20 years of experience. He served as a Cavalry Scout, volunteered as the Training Officer for Superior Search and Rescue, owned and operated his own Consulting Forestry business, and dabbles as a novice knife maker. A Michigan Technological University graduate, he’s contributed to several publications like founded Vargold3T.com—a platform offering free survival courses—and now manages Recoil Offgrid as the Editorial Content Director. Patrick’s experience in managing real-world disasters, and his commitment to sharing his knowledge makes him a trusted and respected figure in self-reliance.

Jerry Saunders is a Marine Corps veteran, Scout Sniper, and former Staff NCO in charge of Survival for the United States Marine Corps, Mountain Warfare Training Center. He has trained U.S. and foreign military units across the globe and is internationally recognized for his work in cold weather survival. Saunders recently moved his company Corvus Survival up to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan where he holds private survival classes and operates a small custom knife shop all while rebuilding an old homestead. Learn more about him at corvussurvival.com.

Read More

Subscribe to Recoil Offgrid’s free newsletter for more content like this.

- What If: You’re Targeted By A Deepfake Cyberattack?

- What If: You’re Faced With a Modern-Day Witch Hunt?

- What If You’re Stranded On A Flooded Jeep Trail?

- What If You’re Isolated for an Indefinite Amount of Time?

- What If You Escaped from a Kidnapping?

Editor’s Note: This article has been modified from its original print version for the web.