In This Article

Dehydration kills. In 2004, a study of the National Hospital Discharge Survey discovered that, in the U.S. over 500,000 hospitalizations were a direct result of dehydration. Sadly, about 10,000 of those resulted in death. In third world countries, this statistic is far greater, with millions of people dying each year. Dig into these numbers a little bit, and you’ll find that often times, these injuries and deaths are not due to water being completely inaccessible. They’re correlated with waterborne diseases and other contaminants from lack of access to clean water.

Even if you don’t live in sub-Saharan Africa, clean drinking water may not always be readily available, especially if you find yourself in the backwoods far away from regulated municipal water sources. The water in that nearby creek might look and smell perfectly fine, but it could contain microscopic pathogens that will make your life absolutely miserable — and severely dehydrate you — if you drink it.

This is where Grayl, and their recently released GeoPress Ti comes in. This 24-ounce water bottle contains a powerful, easy-to-use water purifier, and has a few other tricks up its sleeve.

Above: Multicolored topo map patterns have been laser-etched onto the titanium, adding a little visual flair to the exterior.

Grayl Geopress Ti: Design and Build Quality

When it comes to portable water purifiers, durability is paramount. As the name suggests, the GeoPress Ti is crafted from CP4 Grade 1 titanium, known for its exceptional strength-to-weight ratio.

This material is not only incredibly durable but also lightweight, making the GeoPress Ti easy to carry, whether you’re hiking through rugged terrain or packing light for international travel. The laser-engraved finish adds a nice touch of aesthetic appeal, and the toughness of the material ensures it’ll hold up to serious use.

Above: The two main components of the Grayl GeoPress, the outer cup and inner purifier bottle.

The GeoPress consists of two components: an outer cup and an inner Purifier Press bottle that nests inside it. The bottle portion is equipped with a replaceable, American-made filter cartridge at its base, and a SimpleVent cap with a pour spout and carry handle. Wide, butterfly-style handles on the outer titanium cup fold away when not in use.

This cup can be used in a stand-alone manner for collecting and boiling water or cooking food. However, if you run across a suspect water source, you can purify it in less than 10 seconds with the following steps:

- Fill cup with dirty water.

- Position purifier bottle on top of cup on a flat surface and twist the SimpleVent cap ½ turn to allow air to pass through.

- Using your body weight, press down steadily with both hands until the bottle reaches the bottom of the cup.

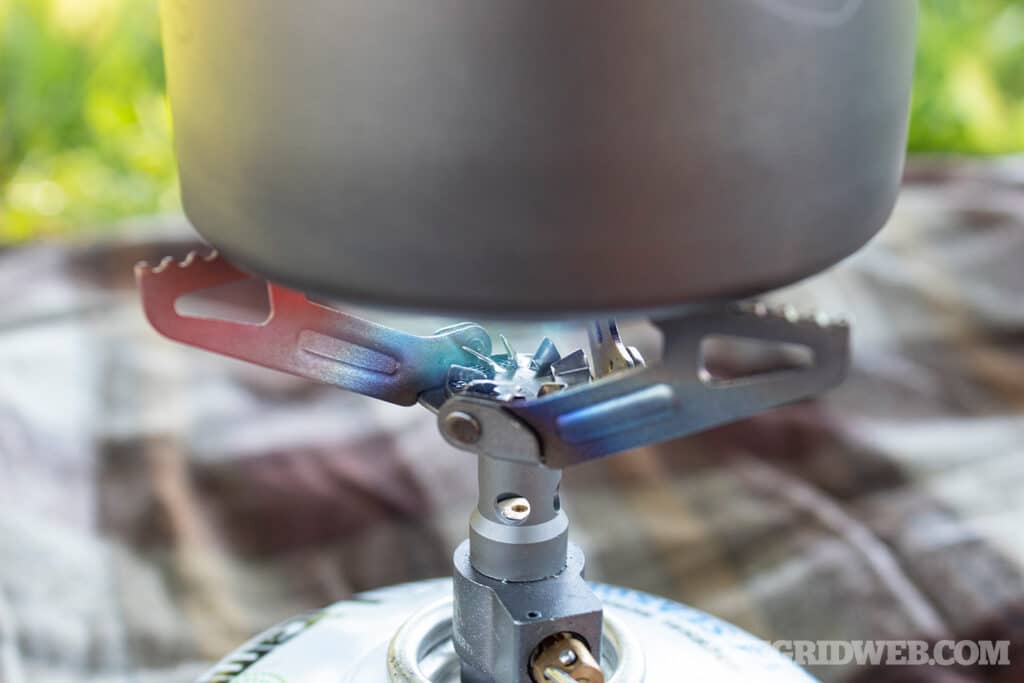

Above: Since the GeoPress Ti cup is metal, it can be placed onto a stove to boil water or cook food.

Grayl GeoPress Ti: Performance in the Field

No review would be complete without real-world testing, and I put the GeoPress Ti to the ultimate challenge. For 10 days, I relied solely on water from a cattle watering hole in Texas, a source so contaminated with feces and other pollutants that it was undrinkable by any conventional means.

The GeoPress Ti not only purified the water, but it did so with remarkable efficiency. I was able to use the purified water for everything from drinking and cooking to hygiene and cleaning. Since then, it’s been a critical piece of gear that accompanies me on every wilderness outing.

Grayl’s OnePress global filtration and purification system is the heart of the GeoPress Ti, allowing you to transform the world’s most dubious freshwater sources into clean, drinkable water in just 8 seconds. Independent lab testing shows that the system removes 99.99 percent of viruses, 99.9999 percent of bacteria, and 99.9 percent of protozoan cysts, including the likes of Rotavirus, Hepatitis A, and Norovirus.

It also filters out particulates, such as silt and microplastics, while activated carbon adsorbs chemicals, pesticides, heavy metals, and odors. In my case, the purifier effectively neutralized the filthiest water I’ve ever encountered, providing me with safe hydration despite the austere conditions.

One of the most impressive aspects of the GeoPress Ti is its flow rate. The ability to purify 24 ounces of water in just 8 seconds is a game-changer, especially when you’re in a situation where time is of the essence.

Grayl’s micro stove is incredibly small and lightweight, but provides a fast way to boil water in the cup. Fuel is sold separately but easily found at Walmart or any camping store.

Multi-Functional Capabilities

While the GeoPress Ti excels at water purification, capabilities extend far beyond that. The titanium construction allows the outer cup to be used as a cooking vessel for heating water over hot coals or cooking a simple meal. Butterfly handles provide a stable grip, ensuring that you can safely pick up the cup even when it’s hot.

Built into the purifier cartridge is a one-way silicone valve, another clever feature that adds to the versatility of this device. It allows you to add electrolytes or a sports drink mix to your water without compromising the integrity of the filter cartridge. This is particularly useful for those long days in the field when you need more than just water to keep going. The valve also enables the use of any other potable beverage.

During my 10-day test, I also appreciated the SimpleVent cap, which protects the spout from cross-contamination and provides a fast flow of water. Whether you’re chugging water on the go or filling a hydration reservoir, the wide contoured spout pours with ease.

Durability and Longevity

One of the key selling points of the GeoPress Ti is its durability. This purifier is built to withstand the harshest conditions, including a 10-foot drop at full capacity onto concrete. I’m not always gentle with my gear, so I appreciate this sturdy design.

The purifier cartridge is rated for 350 cycles, or about 65 gallons (250 liters) of water, before it needs to be replaced. Even after prolonged use, I found that the cartridge maintained its effectiveness, with press times only gradually increasing as the cartridge reached the end of its lifespan. With a shelf life of up to a decade for an unopened cartridge, it’ll remain ready for years to come.

Above: The Gryal GeoPress is easy to use, just fill the outer cup and press the internal filter cup down for fresh clean water.

Ease of Use

In a survival situation, simplicity is key. The GeoPress Ti’s design ensures that it’s easy to use, even under stressful conditions. The Fill-Press-Drink system is intuitive, allowing you to quickly purify water without the need for complicated setup, cleaning, or maintenance. Whether you’re filtering water from a stream, a stagnant pond, or a contaminated source like the cattle watering hole I encountered, the GeoPress Ti makes the process straightforward and efficient.

The ergonomic SoftPress Pads provide a comfortable, non-slip surface for pressing, while the SimpleVent Drink Cap allows for easy venting during the filtration process. The result is a purification system that’s not only effective but also user-friendly.

Our only concern relates to stand-alone use of the outer cup. If it’s filled with dirty water for the purifier, it should be considered contaminated, but it would be easy to pack it away and use it later for a meal. If the cup isn’t thoroughly sanitized between these uses, it might introduce the exact pathogens you’re trying to avoid drinking into your food.

Grayl offers suggestions for how to avoid cross-contamination, such as washing the cup with soap and water or using it to bring water to a rolling boil. Regardless of the method you use, don’t forget to clean the cup before drinking or eating from it directly, otherwise you might regret it.

Practical Applications

The GeoPress Ti is designed for a wide range of users, from outdoor enthusiasts and survivalists to international travelers and overlanders. If you’re someone who frequently finds yourself in environments where clean water is not guaranteed, the GeoPress Ti is an invaluable tool.

Its ability to purify water from virtually any freshwater source makes it ideal for backcountry adventures, international travel in regions with questionable water quality, and emergency preparedness. Some people will even find it handy on vacations to towns in the U.S. where the local drinking water may be less than ideal.

For outdoor recreationalists, the GeoPress Ti offers the added benefit of being able to cook and boil water in the field, reducing the need to carry multiple pieces of gear. Grayl also offers a GeoPress Ti cook lid ($25) which fits the outer cup, and a Titanium Dining Set ($53) with a plate, bowl, and spork that match the GeoPress.

Lastly, there’s a Titanium Camp Stove ($23), which attaches to isobutane fuel canisters from any camping store and can be used for cooking or boiling water. This micro-stove folds up into a tiny bag and weighs only 28 grams (not including fuel).

Above: Grayl also offers this BottleLock Hip Pack ($160) which is made in the USA in your choice of MultiCam pattern (Black, Arid, Tropic, or Alpine). Its 4.5-liter capacity is perfect for small tools, snacks, maps, and other items.

Final Thoughts

My experience using the GeoPress Ti while living off stagnant cattle bath water for 10 days has left me thoroughly impressed with its capabilities. From its titanium construction and rapid purification system to its versatility as a cooking vessel and its user-friendly design, the GeoPress is a great piece of kit and an efficient water purification solution. With the ability to purify the world’s most challenging freshwater sources, this purifier is ready to take on any adventure.

Grayl GeoPress Ti: Specs and Availability

Volume: 24oz

Weight: 20.1 ounces

Cartridge Lifespan: 350 cycles (65 gallons / 250 liters)

MSRP: $220

URL: grayl.com

Read More

Don’t miss essential survival insights—sign up for Recoil Offgrid’s free newsletter today!

- Survival Water Filter: Pure Hydration

- Water Purification: Minimum Boiling Time and Other Methods

- Water Purification: Common Contaminants and Methods to Eliminate Them

- Video: Boiling Water With Just a Knife

Check out our other publications on the web: Recoil | Gun Digest | Blade | RecoilTV | RECOILtv (YouTube)

Editor’s Note: This article has been modified from its original version for the web.